Massachusetts 2050: A Warming State

Editor’s Note: Amherst Wire is launching a new series, “Massachusetts 2050: A Warming State” to investigate the effects of climate change in our communities and how our state is responding to its imminent impact. The series is targeted to ask specific, in-depth questions on what climate change looks like now and will look like in the future, and the hope there is if a change is instilled amongst the public. This series began production a little over a year ago, but was interrupted due to the COVID-19 pandemic and due to this, it contains initial contributions from some of the Amherst Wire alumni.

It is July 4, 2050.

Sweat beads on my head as I make my way down northern Nevada’s Interstate 80. The long dirt road extends ahead with the view of distant mountains. All I can think of is that I need some air.

As I park my car in the Elko City Gas Station with natural gas prices listed at $8, I sigh. I push open the door. It is 120 degrees. A seven-foot rattlesnake leaps towards the car.

I slam the door shut and catch my breath. No matter how many heatwaves accumulate, each one is just as intolerable as the last.

Elko City, as well as Death Valley and other desert towns around Las Vegas, have become even more remote and desolate than they had been before. Casinos are left abandoned as more and more people flee to Utah or Colorado to survive the rising temperatures. Lake Mead looks more like a pond than a reservoir. States that we could go to escape the heat, like California and Oregon, are busy fighting rampant wildfires.

I haven’t been back to Massachusetts since my graduation from UMass in 2020. I am heading back East on a reporting project to understand how the Pioneer Valley, too, has been affected by the warming climate. Everyone has been.

~ ~ ~

“A lot of the science in the last few years leads to this notion that we’re just a few years away, on our current rates of emissions, from having put enough carbon in the atmosphere to reach a world that’s one and a half degrees warmer than it is today,” said Robert DeConto, a UMass geoscience professor, scientist and one of the lead authors of the 2019 United Nations’ IPCC Report (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) “The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate”. According to DeConto, the 800-page report shows projections, most of which are out to the year 2100, of sea-level rise, increased acidity of the ocean, marine heatwaves and the loss of coral reefs.

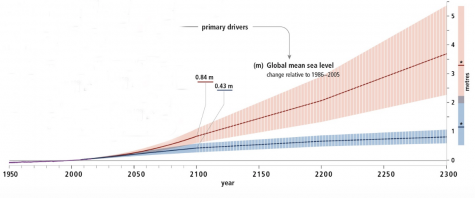

Yet, DeConto makes an important distinction within the devastating figures listed on the IPCC report illustrated by red and blue curves. The red curve projects a trajectory following “business-as-usual.” The blue curve projects a stark contrast with a big reduction in future greenhouse gas emissions, or the projection from the best-case scenario.

“In every case, you see this really strong divergence of the red line and the blue line, whether it’s sea-level rise, the acidification of the oceans, the severity of heatwaves or the loss of coral reefs,” said DeConto. “It shows that here’s a world where we continue a really fossil-fuel intensive future global economy, versus really getting our act together and collectively, globally making a strong effort to reduce emissions.”

According to DeConto, the rate of sea-level rise has more than doubled from the last century with an increase in the frequency of storm surges and nuisance flooding. Some areas are at greater risk than others because sea-level rise doesn’t happen by the same amount everywhere. One of these unlucky areas is Boston.

“[Boston] sits in a place on the East Coast that is experiencing faster sea-level rise than other places around the world,” said DeConto. He shared the effects of sea-level rise to the New England coastline will flood some areas and areas not flooded would be more prone to storm surges. He said while sea-level rise isn’t going to have an immediate and direct impact on central Massachusetts, climate change will.

“The warming that is causing sea levels to go up is also going to cause issues here in the valley,” he said, which includes extreme flood events, shorter winters, with impacts on the insects, fisheries and plant life in central Massachusetts.

The first weekend I visited the Pioneer Valley was before I was in college. It was Earth Day and the annual Amherst Sustainability festival was going on in the Amherst Common. I wasn’t worried about climate change back then.

This last year, I helped report on a walk-out of more than 300 Amherst students and community members. The organizers, collaborating student groups and government officials spoke to the crowd about the need to do something in our state of climate emergency. So, as students and many others around the country have walked out in support of the cause, we have decided to walk in.

For this reason, The Amherst Wire and members of the UMass Journalism department will release a year-long series covering climate change in our nearby communities and the potentiality for hope. These stories will include breaking down research from prominent UMass scientists, talking to student activists, local farmers and fishermen, to tracking down how much plastic a typical student uses and where exactly it goes.

The original contributor of this story is Caeli Chesin, who can be reached on Twitter @caeli_chesin

If you have an idea for a future article in the series or would like to contribute, please email Emilee Klein at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter @emileeklein