“Massachusetts 2050: A Warming State” the fast fashion industry and it’s environmental impacts

What labor practices and environmental impacts are you supporting when you buy into the fast fashion industry?

Editor’s Note: Amherst Wire is launching a new series, “Massachusetts 2050: A Warming State” to investigate the effects of climate change in our communities and how our state is responding to its imminent impact. The series is targeted to ask specific, in-depth questions on what climate change looks like now and will look like in the future, and the hope there is if a change is instilled amongst the public. This series began production a little over a year ago, but was interrupted due to the COVID-19 pandemic and due to this, it contains initial contributions from some of the Amherst Wire alumni.

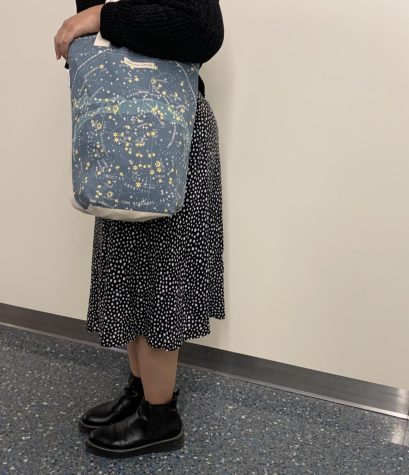

Like this shirt? It could be yours for only $15!

But, how much does it really cost? How much carbon is entering our ecosystem from this white shirt? How much water was used in the making of it? How many times can you wear it before the fabric will start falling apart? Three, maybe four times?

What is fast fashion?

Fast fashion is an approach to the design and marketing of clothing fashion that emphasizes making fashion trends quickly and cheaply available to consumers.

The idealization of the industry has led many Americans to value cost over quality, where our items have become more of commodities than keepsakes. Fast fashion, in turn, feeds into the culture of always wanting more.

While the figures are debated, according to the UN Environment Program, the fast fashion industry is the cause of “10 percent of humanity’s carbon emissions. That’s more emissions than all international flights and maritime shipping combined.”

The goal of fast fashion is to make and globally distribute clothing as quickly and cheaply as possible. From making and gathering materials to importing textiles to factory production to shipping, every practice the industry partakes in is carbon-emitting.

A reporter for the New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal, Dana Thomas, wrote a book, “Fashionopolis: The Price of Fast Fashion and the Future of Clothes”, which describes the industry as the ability to sell clothes cheaply, while also reaping a sizable profit. The book explains how production is outsourced to independently owned factories in developing nations, where there is little or no safety and labor oversight and wages are generally poverty level, or lower.

Thomas reported that, of the fast fashion produced clothing, “20 percent goes unsold,” making the underpaid labor then disposed of in our already overflowing landfills.

“One kilogram of cloth generates 23 kilograms of greenhouse gases,” Thomas writes in her book, whose research included that, on average, each American purchases 70 new clothing pieces a year.

The fast fashion industry also depletes a significant amount of the world’s water supply.

“Non-organic cotton, known as unconventional cotton, is among agriculture’s dirtiest crops,” she writes. “Conventional cotton isn’t much better, as on average to grow one kilo the plant requires “2,600 gallons (ca. 10 m³) of water.”

To contextualize the extreme water usage of the fast fashion industry, according to The World Resources Institute, “it takes about 700 gallons (2.65 m³) of water to produce one cotton shirt. That’s enough water for one person to drink at least eight cups per day for three-and-a-half years.”

There are people and animals who lack access to clean water while the fast fashion industry uses and pollutes what The World Resources Institute quotes as “20 percent of all industrial water pollution worldwide.”

“Every day, billions of people buy clothes with nary a thought — nor even a twinge of remorse,” Thomas reports in her book. People seldom consider all the impacts caused by production before buying a new shirt, and often people do not want to know.

How do we play a role?

In order to better understand how the UMass community contributes to the fast fashion industry, Massachusetts 2050 conducted survey interviews of 61 university students, asking questions concerning their fashion habits.

Many of the questions were aimed at discovering their attitude toward environmentally unhealthy fashion decisions, such as wearing clothing only once or wearing only a small fraction of their wardrobe.

Then came the most crucial question: what stores do UMass students frequent the most?

The top results for UMass students’ favorite clothing stores were American Eagle(12.3 percent), Savers(7 percent), Target(7 percent) and Urban Outfitters(7 percent). While Savers promotes the reuse of gently used clothing, it is important to examine the practices of the other stores to dissect whether they deserve our attention and money.

It is common for corporations to mislead the public with claims of environmental consciousness. For example, while Target had dedicated a whole page to their “sustainable products” and their efforts to reduce their carbon footprint, their sustainable products are actually divided up by individual private labels owned by Target. Out of their 42 different brands, only a handful use sustainable practices.

American Eagle could be considered slightly more environmentally conscious, although many environmental justice proponents, like the Environmental Justice Foundation and Canopy, would say that their goals are not strong enough. They have a stated set of environmental goals, which include a 40 percent reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 and a commitment to ensure that 100% of viscose fibers come from non-endangered forests. The issue with their environmental commitments is that a majority of them do not have a set time pressure. They also claim to commit to using 50 percent more sustainable polyester, which raises the question: what exactly does “sustainable” mean, in this regard?

According to a 2020 Vogue Business article, consumers and experts alike say it’s difficult to know which brands truly meet higher ethical standards while greenwashing, a form of marketing deceptively used to persuade that an organization’s products, aims and policies are environmentally friendly. While many brands claim an environmentally friendly agenda, no one can say, for certain what that agenda is. Less water? More humane sources? Livable wages for the harvesters of the cotton? The term “sustainable” is coined by these companies because it lacks a standard definition.

The fashion industry’s corporate social responsibility has increased through the years via organizations like Fashion Revolution, which creates clear reports about certain aspects of social or environmental impact.

On Fashion Revolution’s 2019 Transparency Index Multiple, Target scored in the 31-40 percent transparency range, meaning they are publishing suppliers lists as well as detailed information about their policies, procedures, social and environmental goals, supplier assessment and remediation processes.

Another one of UMass students’ favorite brands, Urban Outfitters scored in the 0-10 percent in the transparency range, meaning they are disclosing nothing at all or a very limited number of policies.

While consumers are targeted by these “green initiatives,” it is important to investigate further whether clothing was made using sustainable practices in terms of low water usage, no pesticides and fair wages for the growers.

In Conclusion

Let’s consider this shirt again.

How can it be more sustainable? We’ll explore answers in Suggestion for Better Fashion Habits.

Email Chloe at [email protected]

Email Melissa [email protected]

If you have an idea for a future article in the series or would like to contribute, please email Emilee Klein at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter @emileeklein