A college town’s last bookstore

With two prestigious colleges and a flagship university, Amherst was once a town bustling with bookstores. Now, a particular technology giant may crush the last independent bookstore left standing.

November 18, 2015

A tall man with thick-rimmed, circle-framed glasses sits in his tiny office in a basement filled with books. His voice is hoarse, his papers scattered. He recounts the first bookstore he ever owned, Goliards, one of seven bookstores in town. The store was named for the late medieval-early Renaissance band of defrocked priests and monks who roamed around Europe having orgies and writing lewd lyrics to church music, a name so perfectly “scholarly and a little out there at the same time.”

Flash-forward 32 years and that man, Nat Herold, now co-owns the last standing independent bookstore in town.

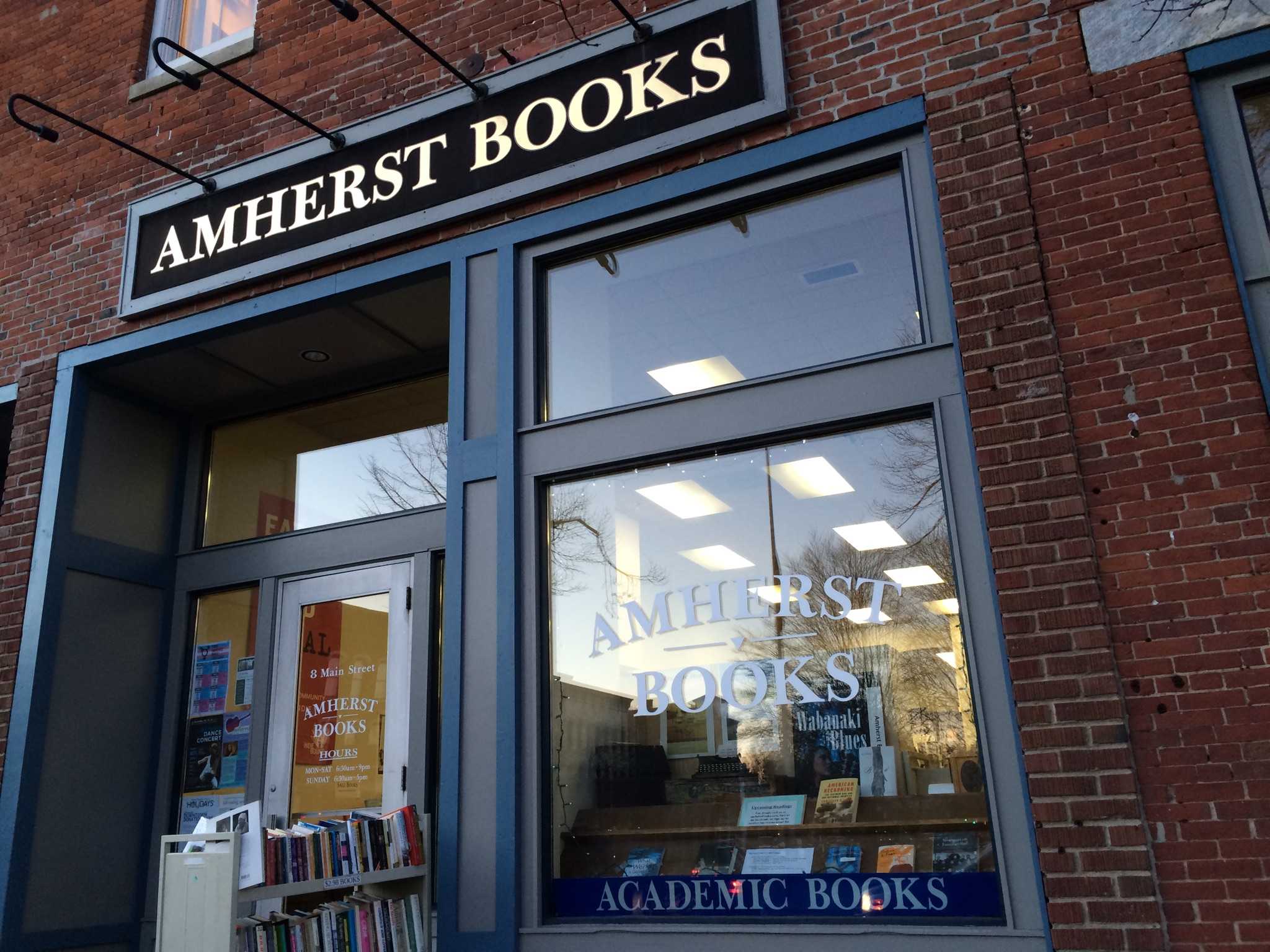

Herold is a bookstore veteran. He and partner Mark Wootton have spent the last decade fighting alongside other bookstores against a shifting digital culture that no longer needs them. The pair bought Amherst Books in 2003, with help from about a dozen investors. Now a charming two-story bookshop on Main Street with used books, new books and textbooks, Amherst Books is the bibliophile’s haven, providing an escape for a leisurely read or spontaneous book purchase.

For others, it is a place to go to take photos of books they later buy on Amazon.

“Amazon is kicking in our last leg,” Herold says while swiping cards through a “Square,” the small Apple device that allows local vendors to perform payments. He sits at a small table with a display of books written by a University of Massachusetts Amherst alum at the university’s Howard Ziff Gallery dedication. The event invited alumni and students to remember Ziff, founder of the UMass Amherst Journalism Department – and an initial investor in Amherst Books.

At 13 different events in the month of October, Herold sold books at UMass, Amherst College and Hampshire College, in addition to 11 events at the bookshop itself. A poetry reading or book launch party accompanied by wine and cheese is a ritual practice.

“I’ve had to start asking people we do events for to contribute a couple bottles of wine,” Herold says.

Back in 2003, the store closed for one to two months for renovations before its grand opening that spring. New computer systems were installed, new wiring fixed, new rugs put in. The bookcases were painted and mounted on wheels, so they could be spun around and rearranged for events.

“We must have had a party or something the first day we were opened,” Herold says, surveying the archives of his mind.

* * *

A few miles away from Amherst Books is a sleek new bookstore with no books. It is a single, brightly-lit room with white walls and three visible employees. Its products are cheap, its customer service renowned – together they ignite an unstoppable force of consumer technology and free market principles. It is called Amazon@UMass.

UMass has followed Purdue and the University of California, Davis in striking up a contract with Amazon to make the internationally recognized e-retailer the official textbook seller on campus. The “virtual bookstore” is located in the Lincoln Campus Center and offers free, one-day shipping on textbooks, as well as two million other products for its Student and Prime membership-holders. Books and goods alike are stored in the state’s Amazon warehouse – rather, “fulfillment center” – in Stoughton.

Kevin Crocker, economics professor at UMass, says that the idea of large corporations monopolizing the textbook market is nothing new at the university: Amazon, he says, is no different than its predecessor, Follett, which ran the university’s former textbook annex. Despite this, Crocker is deeply concerned with the impact corporations have on local bookshops.

“I hate the idea of Amazon being here on campus,” he says. “But I understand it.”

Whether professors order their course textbooks at Amazon or Amherst Books, the process is the same: complete an online form detailing which book and number of students are enrolled and, if the book is not readily available, it can be ordered from the publisher.

Crocker has tried to support local bookstores in past years. To offset costs for students, he worked with publishers to condense a course textbook, picking only necessary chapters, though these shortened copies went to waste when students did not buy them. Food for Thought bookstore, which closed last year, could not return tailor-made textbooks and lost money on those not bought. Now, Crocker uses free, open-source textbooks and online articles to eliminate spending for students.

According to the Daily Hampshire Gazette, the five-year deal with Amazon includes commission guarantees of $375,000, $465,000 and $610,000 to UMass for the first three years, a 2.5 percent commission on qualifying revenues of items shipped to campus, or 0.5 percent on items shipped to the local area. Compared to the Textbook Annex that closed last year and was operated by Follett Higher Education Group of Chicago, students are expected to save roughly 31 percent on textbook costs by purchasing through Amazon.

Director of Amazon Student Programs Ripley MacDonald is pleased with textbook sales this year.

“Our focus isn’t on competitors,” he says. “Students are ultimately the ones who make the choice on where they want to buy their textbooks.”

And students consistently choose Amazon.

Though Amherst Books provides used and new textbooks, orders books on demand, and receives many ordered books within one day like its competitor, it is outmatched. Cheap costs, quick delivery and convenience supplied by the internet mammoth is at the forefront of the typical book buyer’s mind.

The American Booksellers Association, a trade group that promotes independent bookstores, reportedly had 3,100 members in 2000 and only 1,712 members as of May 2015, though membership has steadily increased since the 2007 recession.

Even book “megastores” have taken a hit from Amazon and the popularity of electronic books. The 40-year-old Borders chain filed bankruptcy in 2011. Its longtime rival, Barnes & Noble, has been on a downward trend over the past decade. According to the Wall Street Journal, Barnes & Noble closes an average of 15 retail stores per year, with 42 closures in the past two years alone.

The cheap prices set by Amazon make it increasingly difficult for retail stores to compete.

Though his western civilization professor urged students to buy Marx’s “Communist Manifesto” at Amherst Books, UMass student Jordan Tolbert purchased the book on Amazon for 50 cents, “or 60 cents… something like that.” Amherst Books sells 10 variations of the manifesto, the cheapest selling at $5.95.

“As a college student, you can only pay what you can pay for,” he said.

* * *

Herold is unsure of what the future holds for Amherst Books. The staff is smaller, the work hours longer, the salaries sliced. He does not begrudge students for purchasing cheaper textbooks on Amazon – in fact, he says, if you can save money in school, “more power to you.”

The bookstore’s co-owner says its best customers are tourists, including parents taking their children on college tours in the spring.

“They don’t live near a place where there’s a good bookstore, so they come in and they’re just, ‘Wow,'” he says. “Sometimes they buy books and sometimes they won’t, but they’ll always be grateful that we’re here.”

Email Kristin LaFratta at klafratt@umass.edu, or follow her on Twitter @kristinlafratta.