As demand soars, universities struggle to keep up with surge in mental health patients

April 18, 2017

Emily Dykstra had finally worked up the courage to reach out for help. She picked up the phone, dialed the number for the school’s counseling center and began the process of securing an appointment. When the time came to schedule her first visit, the voice on the other end told her she could be seen in a few weeks.

A few weeks, to her, seemed far too long.

“Mental illness isn’t going to wait … it could get so much worse in that time,” said Dykstra, a junior at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “In that time frame, who knows what could happen?”

Now vice president of the UMass chapter of Active Minds, a national nonprofit organization that strives to eliminate the stigma associated with mental illness, Dykstra has observed the shortcomings of resources at her school.

A boom in patients

Dykstra’s situation is the reality for many college students suffering from mental illness. The demand for counselling has grown fast, and universities have been forced to respond.

With a surge of patients visiting college counseling centers around the country, the Center for Collegiate Mental Health (CCMH) found in their 2015 annual report the average demand for counseling center services grew at least five times faster than average institutional enrollment over the last six years.

According to the report, counseling center usage increased by almost 29.6 percent nationally over five years, while the average institutional enrollment grew by only 5.6 percent.

Harry Rockland-Miller, Ph.D., the director of the UMass Center for Counseling and Psychological Health (CCPH) since 1995, said that the situation at UMass is not unique.

“It’s a national phenomenon,” Rockland-Miller said. “We’re seeing a slow, but steady and consistent increase in utilization both here and across the country.”

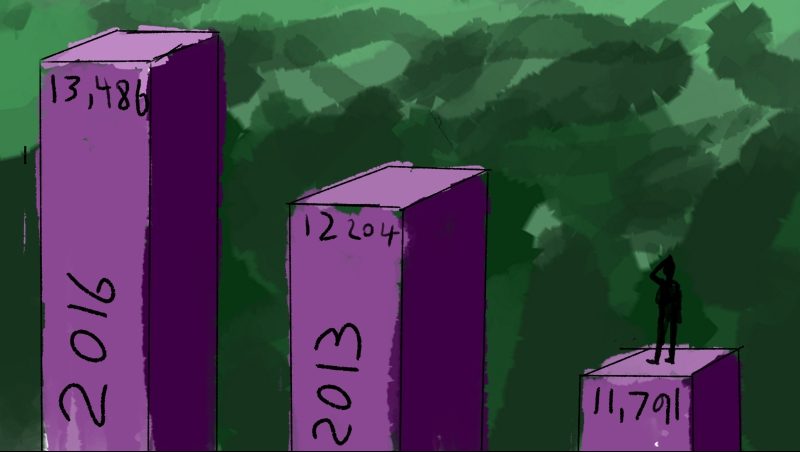

From 2011 to 2012, there were 11,791 total visits to CCPH. The next year, 12,204 visits were paid to the center, followed by 13,486 visits the year after that. Center employees expect the increase to continue, and are estimating 14,184 visits this year.

Rockland-Miller attributes this growth to a variety of factors, including a reduction in stigma against mental illness, increased access to care, change in family structure and earlier identification of people with mental health needs.

Approximately 100 new people come into CCPH every week, Rockland-Miller said. Last year, the center saw 10.5 percent of the total student population — some 2,800 students.

Rockland-Miller said CCPH is handling the increased demand as best as they can with what they have.

The center receives over $3 million in funding each year. The money comes from three sources, the largest being the student health fee, as well as fees collected directly from psychiatric billing and a select number of state-funded employees.

Rockland-Miller said that very few large campuses provide long-term or even medium-term psychotherapy. In the meantime, he said, CCPH has been working to gradually hire more staff to help meet students’ needs.

To Rockland-Miller, mental health must be seen more as an investment. He is impressed by a study done by the RAND Corporation, a research and development think tank. The report explains results from a survey assessing the impact of investment on mental health programs at California public colleges.

The study predicts that with an increase in students receiving treatment, an additional 329 students will graduate because of this mental health treatment every year.

RAND discovered that investing in mental health can increase the welfare of society as a whole. The benefits after an increase in treatment and resulting decrease in dropouts is estimated to be as high as $56 million for every year of increased investment. This is due to an expected increase in lifetime earnings for additional graduates.

In the end, they found the estimated net societal benefit for California is $6.49 for each dollar invested in prevention and early intervention mental health programs.

“I think that every school needs to take a serious look at that,” Rockland-Miller said.

The state of CCPH at UMass

When Iliana Marentes was a freshman, she found herself emotionally at rock bottom.

She walked into CCPH, and within a half hour, she was sitting face-to-face with a counselor who she felt genuinely wanted to help her.

“I think in that moment, it was life changing,” Marentes said of her visit. CCPH was there for her emergency, when she needed support the most.

Marentes, 21, is a junior at UMass Amherst. She serves as a liaison between Active Minds and CCPH. She believes CCPH has great support systems in place for emergency situations.

“It was supportive in more ways than I expected it to be,” Marentes said. “They really were checking in and making sure that two weeks later I wasn’t going back into the hole I was in.”

On that day, Marentes utilized CCPH’s crisis intervention service. When she walked in, they addressed her right away because it was an emergency.

Less extreme cases begin with a phone call. When students initially call CCPH, they schedule a 10 to 15-minute phone call or in-person screening appointment with a clinician. This scheduled meeting helps the center address the nature and urgency of a student’s concerns. It also helps to determine what measures should be taken next.

From there, students will schedule an initial appointment for consultation at CCPH, be referred to a community resource or go in for an urgent appointment. UMass Amherst students are entitled to four free counseling sessions a year covered by the student health fee, paid by all students taking five or more credits per semester. After that, each session is billed to the student’s insurance.

Rockland-Miller said the center has various strengths. CCPH is responsive, collaborative with the community, offers timely care and emergency and urgency access is robust, he said. It also helps students develop a plan, talk to their professors, and help them build a solid support group, said Marentes and Dykstra of Active Minds.

CCPH has a long list of counseling programs for students: individual therapy, group therapy, mindfulness and meditation workshops, “Let’s Talk” drop-in sessions at locations around campus and Connections in Color, a discussion group for students of color. The complete list can be found on their website.

UMass students also have the Center for Women and Community and the Men and Masculinities Center at their disposal, which aid CCPH in serving people on campus.

Centers see wide range of patients

Mental illness can impact anyone. People of all races, genders and sexual orientations have suffered from mental illness and have reached out for treatment.

Rockland-Miller sees patients who come for anything from a situational crisis that they need to talk out one time, to people with various disorders, substance abuse and other long-term concerns.

UMass students predominantly show signs of anxiety and depression, according to Rockland-Miller, which CCMH research has also continually found to be the most common concerns for college students.

The AUCCCD 2016 director survey found that anxiety continues to be the most predominant and increasing concern among college students seeking mental health treatment at 51 percent, followed by depression at 41 percent. Other concerns include relationship concerns at 34 percent, suicidal ideation at 21 percent, self-injury at 14 percent and alcohol abuse at 10 percent.

According to the Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors (AUCCCD), about 34 percent of students treated for mental illness are men, who constitute about 43 percent of the student body as a whole. Women, on the other hand, make up 64.3 percent of students treated, but are only roughly 55 percent of the student body.

Rockland-Miller said that men are underrepresented at CCPH as well, aligning with national clinical trends

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), the discrepancy between male and female patients comes from their willingness to reach out.

“Men of all ages and ethnicities are less likely than women to seek help for all sorts of problems —including depression, substance abuse and stressful life events,” the study said.

Transgender students make up less than 1 percent of mental health patients on college campuses, a number that roughly reflects their portion of the student body. However, transgender people as a whole have one of the highest rates of suicide attempts of any population.

Over 40 percent of transgender people attempt suicide at some point in their life, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Expanding their role

Dykstra emphasized that the timespan between routine appointments at CCPH can often be troublesome.

To her, the overarching problem is that CCPH is understaffed in relation to the the size of the university, leading to a delay in care for routine appointments.

“If they expanded to twice the size that they are, it would make a huge difference,” she said.

There are 34 counseling staff members — 24 professionals and 10 trainees who are receiving more advanced degrees but are qualified to see students.

According to Rockland-Miller, the average time between phone screening and first meeting is nine days. He pointed out that certain months are busier than others, which can impact wait time. Especially by the end of spring semester, the number of patients they’re seeing has been building up since the previous fall.

Because of these constraints, CCPH is primarily focused on short-term treatment. The center often refers students to off-campus resources if they need continual care.

According to Marentes, preventative care also needs to become a higher priority for the university.

“My question is, why do we wait until that point? You don’t wait until you get cancer to go to the doctor,” Marentes said.

“They’re putting so much effort into these emergency situations, but there’s many people who do feel pushed to the side,” Marentes continued. ”From the student’s perspective, you can sometimes feel ignored, which is the worst feeling when you’ve finally gotten the courage get help.”

However, Rockland-Miller said the capacity for center to offer preventative care is somewhat offset by the need to respond to direct clinical requests.

“I think we’re doing as much [preventative care] as we have the capacity to do. I’d like to do more, and we have done more and more every year,” he said.

A national shift

Emily Dykstra’s experience with having to schedule distant appointments is actually part of a national change, according to CCMH.

She is not the first student to observe UMass prioritizing emergency services to cope with the rising population of students finding their way into waiting rooms. It all comes down to who must be seen right away — and who can wait.

The 2015 CCMH report states that students with a history of “threat to self” thoughts or behaviors, such as serious suicidal thoughts and self-injurious behaviors, use 27 percent more services than students who do not.

CCMH also found that many schools have attempted to meet the climbing number of students in need by reallocating resources to prioritize emergency cases.

UMass has been doing this for years, according to Rockland-Miller. He explained that the university was actually a leader in the nation for developing what is known as a clinical triage system. Within this system, there are three degrees of care: emergency, urgent and routine.

“If the demand exceeds your immediate capacity, which at most large universities it does … you have to decide who you’re going to bring in first, and who you’re going to bring in second,” he said. “You never want to miss someone who is emergency or urgent.”

Emergency individuals will be seen right away, and anyone classified as urgent will be seen in 72 hours.

For UMass Amherst students, CCPH has an emergency line that is operated 24/7. During regular business hours, students can call 413-545-2337 for immediate attention. On weekdays after 5 p.m., weekends and holidays, students can call University Health Services at 413-577-5000.

For more information on services and resources, visit the CCPH website.

Amherst Wire writer Jon Decker contributed reporting.

Email Amanda at [email protected], or follow her on Twitter @Amanda_Levenson.

Email Jon at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter @Jon_H_Decker.