The rainbow diet: Surviving anorexia and gay body expectations

One student tells his story of living with an eating disorder for almost five years and the body ideals that caused it.

May 11, 2018

On the surface, University of Massachusetts Amherst freshman Jacob Russian is just like everyone else.

He wakes up from his bed in his Southwest Residential Area dorm, maybe glances at his phone for a few seconds, and starts off his day by following his basic morning routine. He’ll then get dressed in an outfit he thinks will look nice for the day.

But, if for whatever reason it doesn’t pass his standards, he’ll strip back down and try on a new set of clothes in the hopes of finding an outfit that’ll make him look thinner than the previous one did.

Russian’s retelling of his daily life brought back flashbacks of myself, a 207.8-pound freshman in high school, attempting to pick out clothes that would properly hide the excessive fat on my body. While our thought processes were similar, even sharing the repressed realization that all the clothes we tried on looked the exact same on our bodies, there’s a catch to Russian’s story.

He is far from being considered obese, or even overweight. Instead, he teeters on the lower end of what the body mass index scale deems “average” and “underweight;” a result of his five-year battle with a severe eating disorder known as anorexia nervosa, often shortened to anorexia.

Anorexia is a chronic mental illness where a person suffering from it finds themselves restricting their food intake in order to become thinner; usually resulting in them reaching an unhealthily low body weight and holding an extreme fear of gaining weight.

According to the National Eating Disorder Association, anywhere from an estimated 0.3 percent to over 2 percent of people will suffer from anorexia in their lifetime. Out of these estimates, men make up around 0.1 to 0.3 percent of the statistics — however, these numbers could be higher due to men being less likely to seek treatment from eating disorders due to the stigmas surrounding them.

“The [medical] field has unfortunately viewed eating disorders as a women’s issue,” said licensed clinical psychologist Jennifer Lexington, who has been working as a staff psychologist for UMass’s Center for Counseling and Psychological Health for the past 13 years.

Russian is also part of the disproportional amount of men with eating disorders — an estimated 10 million. Of that number, 42 percent identify as gay.

“It doesn’t start out as toxic as it becomes,” said Russian. Since the eighth grade, he has gone through two periods of drastic weight loss caused by starving himself, multiple years of counseling, and countless restricted or missed meals.

At his worst point, occurring just one year ago in spring 2017, simple acts such as standing up would leave him feeling dizzy.

While he knew there was an issue with how his body was acting, he refused to admit that his low weight was the cause of his deteriorating health.

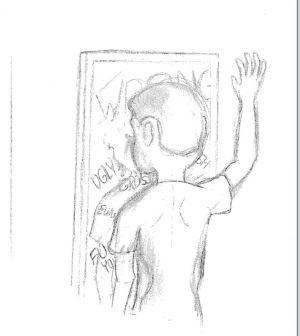

“The more I participated in the things I was doing the worse it got, and it just changes your entire mentality and your perception of your body,” said Russian.

Even now as he continues to slowly recover after a challenging first semester of college, Russian still struggles with deciding what he wants to put into his body and then having to stare at the aftermath of his meals in the mirror.

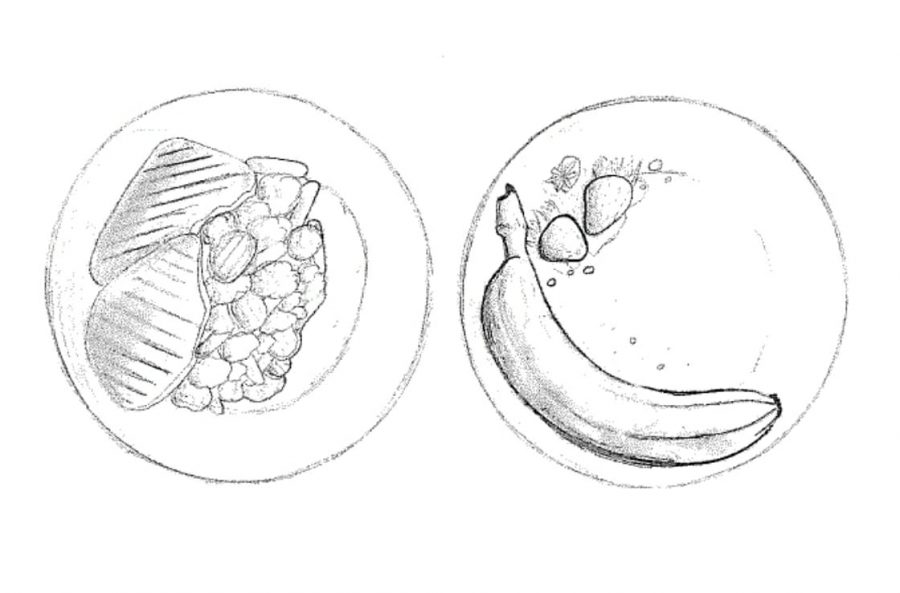

Before he puts anything on his plate at the dining commons, Russian will always take a moment to look at the nutrition label for any item that catches his eye. He’ll scan over the palm size card to check the calories, serving size, etc., and decide whether or not it will be something that, in his mind, will make him gain weight.

“When it was at its worst, I would just look at the calories,” said Russian. The foods he would eat would mostly be based on if they had a low calorie count. After coming to a realization about his health during the winter break before his second semester of college though, he now tries to hold himself more accountable for his eating habits.

“If you have an eating disorder, when you come to college, it gives you a lot of freedom and a lot of opportunities to not take care of yourself,” said Russian. The lack of supervision that college provided allowed Russian to skip out on meals as he pleased with no one there to bother him about it.

Once done eating, the food that had just entered his body would have an almost immediate effect on him — not on his body like most would think, but on his mind.

“If I go to the bathroom and I look in the mirror, I feel like I can see what I’ve just eaten,” said Russian, and he is not alone with these thoughts.

Over her 13 years at CCPH, Lexington, who takes an interest in GLBTQ issues, has encountered a number of people, including gay men, who have struggled with eating disorders.

“I think a lot of gay men I meet with put a precedence on body image,” said Lexington, who attributes this trend to the gay community’s heightened focus on one’s attractiveness. From her observations, it can be easy for gay men to feel the need to be thin or muscular and partake in unhealthy behaviors, such as starvation and excessive working out, if it means there’s a better chance at finding their perfect partner.

However, for Russian, his eating disorder still progressed during his three-year relationship with his current boyfriend; even reaching its harshest point.

“Although I’m dating my boyfriend, I feel almost uncomfortable because I feel like I’m being judged based on how I look; regardless of if that person is interested in me,” said Russian. “Because I perceive the expectations of the gay community as so harsh, I’m almost like afraid being around more gay people because I wonder what they think.”

When he came out as gay in the latter half of his middle school career, Russian felt pressured to find acceptance in his newly joined community — the hope being he could find a place where he belonged. This then became the basis for what grew into his eating disorder.

“When I was coming out, I already felt like I didn’t fit in with anyone around me,” said Russian, whose friend group growing up consisted entirely of straight people. Even now in college, the only gay male he talks to on a regular basis is his boyfriend. “As a way to fit in … naïve, young Jake thought that the best way to fit in would be to look like a group that already existed in the gay community and being thin and looking young would probably be my best shot at that.”

Sub-groups in the gay community, like the one Russian described, are a prominent part of gay culture in the U.S. The terms associated with them can be found integrated in top downloaded gay dating apps, such as Grindr and Scruff, as well as being part of the everyday vocabulary for most people who are connected to mainstream gay culture.

It’s a culture that can seem almost hidden to those who don’t inhabit it.

“To straight people, gay people are just a group,” said Russian. “I don’t think they realize how [the gay community is] partitioned internally and how there are different body expectations for different people.”

This aspiration to fit in with these expectations and body ideals, along with feeling a disconnection from other gay men, is what he attributes to his “distorted view” of what regular gay men may think of him.

That connectedness to the gay community that Russian was missing while growing up has been found to possibly lessen the likelihood of gay men to develop an eating disorder.

To help gay men feel this sense of connectedness, Russian thinks their needs to be a change in the overall mindset of how the gay community shows tolerance and acceptance to its members, as well as a change to the kind of body of expectations they push on them, too.

“Passive acceptance for the perpetuation of unrealistic stereotypes within the LGBTQ+ community must be denounced and terminated,” said Russian in a Daily Collegian op-ed he wrote last January about the issue of gay stereotypes. “We must all consider the detrimental repercussions of allowing entirely unreasonable beauty standards to infiltrate the consciousness of developing young adults.”

While he is now comfortable sharing his story in hopes of shedding light on what he believes is an underrepresented issue on college campuses, it doesn’t mean recovery will be something that’s soon to come.

There are no solid estimates on how long recovery can take people going through an eating disorder, as it varies from person to person and for many, the end may seem out of sight. Some, including Russian, even believe they are struggling with a disease that can’t be beaten, only held off.

For Russian, his condition has been slowly improving as his second semester of college comes to a close. When he returns to his hometown of Milford, Massachusetts for summer break, he does plan on seeing a counselor again, but his past will always leave him uncertain for the future.

“The thing with eating disorders … at least in my opinion, you can’t really escape them forever,” said Russian. “It kind of waxes and wanes.”

However, that doesn’t mean he’s ready to give up any time soon.

Email Brian at bchoquet@umass.edu or follow him on Twitter @brianshowket.