Not Here, Not Now, Not This Family

This is the story of Lucio Perez, a Guatemalan immigrant who has been living in sanctuary at First Church Amherst for over two years.

March 25, 2020

Reporters Note

My reporting process consisted of interviews with various members of First Church Amherst, extensive secondary research about various forms of immigration and sanctuary law and from my own experiences at First Church Amherst. All quotes are verbatim except when bracketed words are added for clarity or a change to past tense. I used Trint, an AI powered transcription service to create a transcript of all the interviews I conducted. Because of my inability to speak Spanish, a translator was present with me during my interview with Lucio. I used two articles from the Daily Hampshire Gazette to fill in a few gaps in my reporting, specifically about Lucio’s encounter with two police officers in Hartford CT and when he left Cooley Dickinson Hospital. I personally attended the two-year event for Lucio.

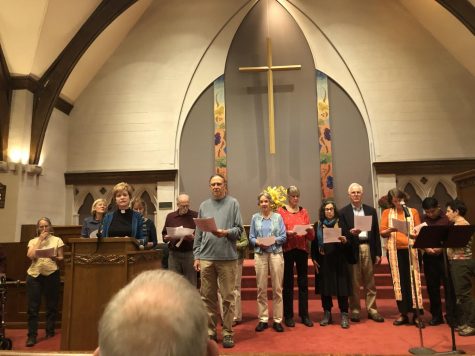

At first glance, First Church Amherst seems like any other church in a small New England town. Gothic architecture, grey brick, imposing yet extravagant from the outside, but rather modest on the inside. A chest-high wooden pulpit stands in the sanctuary next to a flower-filled vase, and a large wooden cross is suspended from wires connected to the ceiling. A guitar rests next to a speaker and microphone. A lush red carpet engulfs the floor, suppressing the sound of churchgoers’ footsteps.

There are over 11 million undocumented immigrants currently living in the U.S. The National Sanctuary Movement found that only 36 of them were living in sanctuary in 2018. This is one of their stories.

Lucio Perez, an undocumented immigrant from Guatemala, has been living in sanctuary at First Church for over two years—888 days as of Tuesday, March 24, 2020. On October 17, 2019, First Church Amherst rang the church bell 730 times to illustrate his time in sanctuary. Camera crews and reporters from all over Western Mass. were there to inform the world that he’s still living there.

Sanctuary is legally defined as “a place of refuge, where the process of law cannot be executed.” However, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), “a city may call itself a ‘sanctuary city’ or a ‘welcoming city’ without implementing any new policies.”

Reverend Vicki Kemper, the pastor at First Church Amherst, approached the podium. Lucio sat in the front-most pew with his wife and three children. It was the only day that week they saw their father.

“None of us could have imagined that two years later, Lucio would still be here,” Rev. Kemper announced.

On January 25, 2017, President Donald Trump issued the Executive Order “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States,” which declared the administration’s immigration and removal policies. The EO denounced sanctuary laws, claiming they “have caused immeasurable harm to the American people and to the very fabric of our Republic.” The EO also threatened to defund sanctuary cities, which was deemed unconstitutional by the Department of Justice. According to the Center for Immigration Studies, only nine states have “laws, ordinances, regulations, resolutions, policies, or other practices that obstruct immigration enforcement and shield criminals from ICE.”

Rev. Kemper began preaching sermons about immigrant justice in early 2017—how to prepare for anti-immigration policies and support immigrants and refugees. In June of 2017, the church voted to become an immigrant-welcoming congregation, making a commitment to promote immigrant justice.

According to the SPLC, “sanctuary policies and laws restrict when and how local law enforcement can engage with the federal government in immigration enforcement, in order to maintain local law enforcement’s ability to work with and in the immigrant community.” Cities cannot protect someone from deportation but can ensure the federal government cannot enforce immigration laws. Amherst’s Sanctuary Bylaw states that no Amherst police officer can participate in “federal immigration enforcement activities, including participation in inquires, investigations, raids, arrests or detentions that are based solely on immigration status.” The bylaw also ensures the Department of Homeland Security cannot “deputize local officers as immigration agents, like those in place at Bristol and Plymouth Counties.”

Becoming a sanctuary church was something First Church was not well-suited for. In June of 2017, it was undergoing major renovations. “The building was torn up. Literally, you could not get from the first floor to the second floor, and it was going to become even more torn up,” Rev. Kemper said. “Also, we didn’t have a shower or anything like that. We felt we weren’t well suited to offer sanctuary to someone.”

Just a few months later, on October 18, 2017, Lucio showed up at their doorstep, asking for sanctuary.

He had 24 hours until ICE sent him back to Guatemala.

“We will continue to stand with Lucio and his family,” Rev. Kemper declared.

After the audience sang “Paz y Libertard” (Peace and Freedom), Lucio walked up to the podium to give a speech. Lucio had notes, but rarely looked at them; his speech was genuine. Reverend Margaret Sawyer translated for the audience.

“We’re walking on a journey God wants us to be walking on altogether; God gives us the strength to keep going forward.” He looked at his children. “I think all of us who are mothers and fathers know how difficult it is to live away from our children.” Sanctuary has been an immensely difficult obstacle for his children; Tony, Lucio’s second-oldest son, worries about his mom’s ability to care for four children by herself. Lucy, his daughter, spent almost all last summer at the church because she didn’t want to be away from her father.

“I see them arrive almost every week and they always greet their dad with a tremendous amount of love and care,” Toby Bobbitt, a member of the Sanctuary Working Group said.

“Two years is short, and two years is long; I’ve learned to not turn my back on others,” Lucio added. “I thank you for looking towards the future.”

A Life-Altering Encounter

In 2009, Lucio, his wife Dora and their children stopped at a Dunkin’ Donuts in Hartford, CT. The parking lot was full, so Lucio parked in an emergency spot. He told his children to come with him, but they refused. Lucio went to get coffee while his wife went to the restroom.

“Wait for me, I’ll help you carry the drinks,” she said. Less than five minutes later, as they were leaving, two policemen were behind the car.

“What’s wrong with you?” One of the policemen yelled at him.

That’s when the problems began. The Daily Hampshire Gazette reported Lucio was arrested, charged with child abandonment and given a deportation order by ICE. He was given five stays of deportation by the Obama Administration, but was ordered to leave during his first check-in with ICE after President Trump was elected.

The deportation process isn’t instantaneous; detained non-citizens have the right of counsel, access to courts and the right to bond hearings when detention becomes prolonged. Although Lucio had access to a lawyer, he failed to provide proof of residence and documents that confirmed he’d been in the country for 10 years.

Lucio’s lawyer suggested he file an appeal claim, which he did. According to the Immigrant Legal Resource Center, an appeal is heard by the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA). If the BIA finds the judge made the wrong decision, the case will be sent back to redo the decision, and possibly the entire case. If the BIA agrees that the person is eligible for deportation, the person will be issued a “final removal order” that allows the Department of Homeland Security to deport them. As a result, the process can take anywhere from a few weeks to more than a decade.

(Harry Ortof/Amherst Wire)

Until The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRARA) was passed, immigration law declared “in any case in which an alien is ordered deported from the United States under the provisions of this Act, or of any other law or treaty, the decision of the Attorney General shall be final.”

For an entire year, Lucio didn’t hear from his lawyer—whenever he called, there was no answer. Finally, on September 13, 2017, his lawyer called him.

He had 35 days to leave the U.S. ICE required that he bought a one-way ticket back to Guatemala.

That same night, 43 members of First Church Amherst held an emergency congregational meeting. “This is literally unheard of, that a call went out and less than 12 hours later, we had a meeting,” Reverend Vicki Kemper said. Lucio arrived at First Church through the basement entrance with his daughter and a close family friend. “We said to [the congregation], here’s the situation: he’s supposed to report to ICE tomorrow—he could need sanctuary as soon as tomorrow, or he may just want to continue to pray and think about it for a few weeks.”

They didn’t know what providing sanctuary would entail, or how long Lucio would need it. But the scripture study, the prayers and the situation facing immigrants were clear—their faith called on them to work for immigrant justice.

“People understood that,” Rev. Kemper said. “But what was hard was for some people was the fact that we had virtually no process around this. It was like an instantaneous thing. And so literally, no one said, I don’t think we should do this. There were two or three people who said, I’m uncomfortable with the process we’re using to make this huge decision so quickly.”

After over two hours of discussion, the church unanimously voted to offer Lucio sanctuary.

Ralph Faulkingham, a member of the board of trustees and the clerk of the church, recounted that night.

“It’s still seared into my memory, the sense of the hair rising on the back of my neck as I realized that we were embarking on something where we really had no idea… we’re just taking a leap of faith and hoping that we can pull it off. I still look back at that time as a time of enormous anxiety and that maybe we’re making the wrong decision. But at the same time, I think most of us felt we could not turn our backs on this man.”

A Sunday school room became Lucio’s permanent home.

(Harry Ortof/Amherst Wire)

When I initially went to First Church Amherst to speak with Rev. Kemper, I was intimidated by the brass metal doors looming over me; they seemed too hostile for a church. On the door was a phone number I had to call to be let into the building. On a small side door to the right, another piece of paper said, “PLEASE MAKE SURE THIS DOOR LATCHES BEHIND YOU WHEN YOU LEAVE.” I was confused—weren’t churches supposed to be accessible to everyone? Rev. Kemper later explained that locking the building was one of the changes made after Lucio entered sanctuary. They also had to create a training and organization system for people to be in the building with him 24/7. There are specific guidelines the volunteers must follow.

The guideline document states “accompaniment work is primarily about being a physical presence at the side of those who have made the difficult decision to enter sanctuary. Although you may feel a pull to protect Lucio and others in sanctuary, your primary job is simply to be here.”

Ralph accompanied Lucio during the first few nights of his sanctuary. “I was sleeping overnight from seven p.m. to seven a.m., and I did not sleep well.” Ralph was in the Hawley room, which is tucked away in the northwest corner of the church basement. He slept on a cot in his sleeping bag, anticipating the worst-case scenario. “I had keys, I had my cell phone available, I had an attorney’s number to call. If it was anybody from ICE, I knew exactly what to say, I’d been trained. I was half expecting something like that to happen. But we’ve had no evidence that ICE came near or even contemplated violating the grounds of the church or stepped foot on church property.”

The Board of Trustees made sure part of the donations were used to support Lucio’s family—a membership to the YMCA so his children could have something to do after school, or an iPad for Lucy so she can FaceTime her father.

But sanctuary requires far more than money or volunteers. It requires surrender.

Surrender of schedules. Surrender of time and energy. Surrender to an amoral political system that believes sanctuary laws have desecrated our country. Surrender to ICE agents, politicians and lawyers that answer to different value systems than people of faith. Lucio is imprisoned, waiting for legal justice to take place.

“You just have to be willing to put your own and the church’s plans on the shelf to an extent, because [sanctuary] has a tendency to take over a lot of things because it’s very demanding,” Rev. Kemper said. “But at the end of the day it’s about the core of our faith, which is loving God by loving our neighbors.”

Sanctuary also requires Lucio to give up his independence. He might have to return to Guatemala after over two years of living in sanctuary. He cannot work, cannot live with his family, cannot leave the church without fear of an ICE agent detaining him. His family is deprived of a father, something many families take for granted. He makes phone calls to check in on his kids at night—his wife Dora calls him during her work breaks.

Community and Faith

Because First Church Amherst is part of the United Church of Christ, their polity is different from other churches. Some churches have bishops and priests who make choices for their church. Congregational churches don’t have hierarchy—they make choices together. They believe there is no ‘best’ way to do something, and that God can speak through anyone.

“We take great care when we make decisions… to me, that feels like the right way to make decisions,” Rev. Kemper said. “We value everyone being involved more than we value efficiency, and we value everyone having a voice over clear lines of authority.”

Over the past two years, a community has grown around First Church—people from all walks of life have come together to support Lucio and his family during his journey. First Church Amherst has seen about 400 different households donate in some way, shape or form. Volunteering to drive Lucio’s family to and from their home in Springfield, cooking meals, accompaniment work, gathering for potlucks, all of these have been around the same central idea—providing Lucio with a loving, supporting community. About 35 to 40 people sustain Lucio on a weekly basis.

(Harry Ortof/Amherst Wire).

“It’s just been an incredible outpouring of support,” Ralph said. “I’ve made friends, I’ve come to see allies in places I didn’t imagine. So, it’s been enormously heartening to realize what an incredibly rich, caring community that I’m a part of.”

Sanctuary isn’t like signing a petition or casting a vote. It has a clear, immediate difference in someone’s life.

Religion, especially Christianity, plays a large part in many Guatemalans lives. A study done by the Global Religious Futures Project found that over 95 percent of Guatemalans identified as Christians in 2016. But for Lucio, it’s more about his relationship with God.

“Your faith always has to remain active,” Lucio said. “Because faith is what moves mountains. Our trust always has to be with God, even if we’re going through something difficult.”

And he did go through something difficult. Something completely unforeseen.

An Impossible Choice

Sunday, May 13, 2018. Mother’s Day. 207 days after Lucio entered sanctuary. The congregation members celebrated in the morning with food and each other’s company. In the afternoon, after the celebrations, Lucio felt a very sharp pain in his abdomen. At around midnight, he started vomiting—a lot. Lucio thought it was just a virus, but the pain worsened. The next day, he met with his team. Something wasn’t right. They asked if he was feeling alright—they didn’t see how sick he was the day before. He told them about the sharp pain and vomiting, and they became very worried.

“I think you’re really sick,” someone declared. “We’re going to call your doctor.”

At around 7 p.m., a doctor arrived to examine Lucio.

“I don’t know what you have, but it can be really bad,” she told him. “You have to go to the hospital.” He said no.

Because of the ankle bracelet Lucio wears, ICE always knows his location; leaving the church could lead to his deportation. The doctor begged him to go to the hospital. He said no again. She gave him some painkillers, which gave him a fever. He started to sweat. “Now you really have to go to the hospital. the doctor stated. “I’m not leaving until you go.” With his condition getting worse every minute, Lucio decided it was time to go to the hospital. He didn’t care about the risks—his health was more important than getting detained by ICE. Lucio was transported to Cooley Dickinson Hospital for an emergency appendectomy. He was there for four days.

“No fue fácil.” It wasn’t easy.

As an equal opportunity health care provider, Cooley Dickinson worked closely with Lucio’s team to make sure ICE didn’t detain him. The Daily Hampshire Gazette reported during his return to Amherst, “more than two dozen people — local religious leaders, politicians, activists and concerned supporters — turned up at the hospital on Thursday to form a caravan of support for Perez, who rode in a car with the Rev. Vicki Kemper of First Congregational, Northampton Mayor David Narkewicz and the Rev. Peter Ives of Northampton.” Cooley Dickinson released a statement, stating they “[have] not, and will not, provide immigration authorities information regarding our patients unless compelled by law.”

Ringing the Bell

After a prayer for Lucio and his family by Reverends Jose and Maria Pagan, the churchgoers line up in front of a side door on the left side of the sanctuary. Behind the door is a bare concrete room with a long piece of rope dangling from the ceiling. When the rope is pulled, the large church bell rings out for all of Amherst to hear. Three women stand in the room to count the rings and help people pull the rope. Each of them held a piece of paper with tally marks on it.

I’ve never rung a church bell before, so I ask one of the women what I’m supposed to do.

“Just pull down with all your might, then let the rope slide through your hands,” one of them tells me. “Do it as many times as you want.”

I grip the rope with both hands and pull with all my might. A few seconds later, I hear the bell make a loud and satisfying DING. I pull down on the rope again, hoping the bell is loud enough for someone in Washington D.C. to hear.