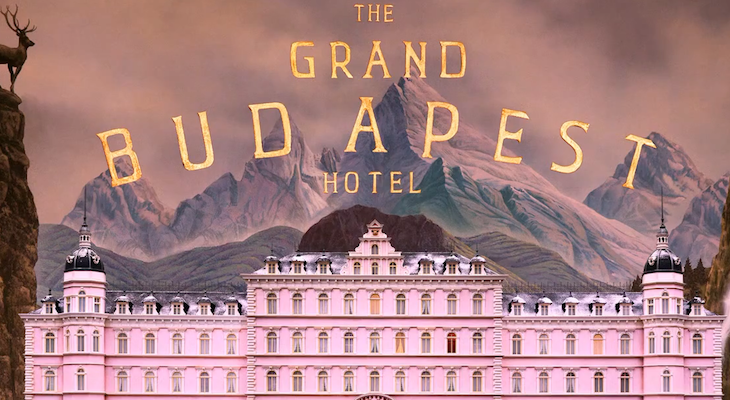

Extravagance through simplicity: an analysis of The Grand Budapest Hotel

There has been an incredible rise in big budget films and productions. A film just 10 years ago would have been thought to have a “massive” budget of 100 million dollars, but now, we see that it is the “norm” for films to exceed that number. More than 20 films in 2014 had budgets of over 100 million dollars. Within these “blockbusters,” we see a substantial increase in action flicks, particularly of the superhero genre, and more movies depicting lavish lifestyles.

Two of 2013’s biggest films were Martin Scorsese’s “The Wolf of Wall Street” and Baz Luhrman’s “The Great Gatsby.” Both of these films showed offensively indulgence, and both, unsurprisingly, were made with budgets of 100 million or more. These films also both received critical success and were honored with nominations at the 86th Academy Awards. Aside from the visual effects category, “major” Oscar contenders like “Birdman” this year had a budget of more than 60 million dollars. These smaller budgets don’t limit the film’s illustrations of luxury especially in “The Grand Budapest Hotel.”

“The Grand Budapest Hotel” is such a complex story that the director, Wes Anderson, divided it into seven “chapters.” The movie starts with an old man telling a story, one that was shared with him years earlier by the owner of the once extravagant Grand Budapest Hotel. Multiple sub-plots unfold including a mystery murder, a stolen painting, a love story, and a wrongful prison sentence. Much of the story takes place, and is told, in The Grand Budapest Hotel and Anderson truly makes this hotel look decadent.

Anderson is known to be a unique director and right now, that’s what the film industry needs. He has a very distinctive style, one that can be described as “quirky.” Anderson, who is as adept at writing screenplays as he is at directing, writes his own screenplay for each movie he creates. He is also known for his use of “ensemble casts” for his films, and seems to enjoy casting Bill Murray and Owen Wilson, both of whom he has worked with seven times. Anderson produces a film about a hotel suited only for the wealthiest people of the time on a budget of 30 million dollars; by today’s standards for films, that is an incredibly frugal feat.

The production design team was helmed by Adam Stockhausen, who worked with Anderson previously on “Moonrise Kingdom,” with Anna Pinnock. The motifs portrayed in this film are noticeably colorful and artistic, in a very simple, almost childish way. There is a scene where the audience is watching one of the main characters take a trolley up the side of the mountain to reach the hotel. As the scene pans out, the audience can clearly see that the trolley and hotel are no more than cut out pieces of paper on a backdrop. In any other movie, this would seem like a lazy special effect, but Anderson and his production design team makes the hotel look unquestionably luxurious.

In a separate scene, the camera zooms out from inside the dining room of the now-decaying hotel. Even as the viewer is meant to believe that the hotel is falling apart, the dining room looks so decadent that it would be a surprise to no one if a ball was to be held there that evening. Anderson is no stranger to fabricating cinematographic environments with his production design team; he did a beautiful job with painting a colorful, innocent picture of the wilderness for his characters in “Moonrise Kingdom,” and again with “Fantastic Mr. Fox,” using stop animation as his medium.

There is always going to be the argument that more money brings more box office success and finding ways to illustrate extravagance is a skill that very few directors possess. While smaller budget films pave the way for the artistry of cinema, it can also be found in independent or smaller budget films such as “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” and this year the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences agreed.

Jesse Hernandez can be reached at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter @jesseroberto812