The importance of language and value: Panel speaks following the screening of “Talking Black in America”

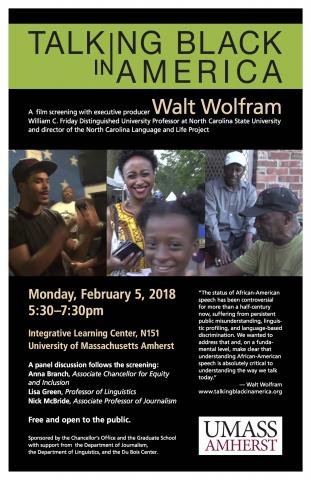

(Photo courtesy of the UMass journalism department.)

AMHERST — What distinguishes African American speech from American speech? How are the differentiations of sounds recognized by the general population? How is the speech, therefore, regulated and reformed to fit into an institutionalized structure? What false narratives are associated and how do these narratives contribute to the oppression of African American communities?

The 2017 documentary “Talking Black in America” was screened Monday night in the Integrative Learning Center, followed by a panel consisting of Executive Producer Walt Wolfram and three University of Massachusetts professors who expanded and questioned points brought up in the film. The room was then opened for a Q&A.

The event was sponsored by the Chancellor’s Office and the Graduate School with support from the journalism department, linguistics department and W.E.B. Du Bois Center. In the large auditorium sat several students who traveled with their teacher from Springfield’s High School of Commerce, along with university faculty, staff and students.

The film covered African American English as a misunderstood variety of speech in America, in which linguistic discrimination affects the way educational achievement and literacy is perceived. The one-hour documentary interviewed an array of linguists, historians, teachers and various others, young and old, on the value of African American language, the effects of linguistic isolation, the great varieties living within African American speech and its history.

“Language is music,” said linguist Arthur Spears in the film’s opening sequence. “There are many types of Black English here in the United States … The language can give you access or it can give you a barrier.”

In the film, UMass Linguistics Professor Lisa Green speaks on the development of African American English, stating that the systematic process starts early on in development. She challenges the notion of African American English being perceived as broken or as “mistakes,” in comparison to the standardized “right way” of speaking that is often perpetuated in classroom and professional settings. New York University linguist Dr. Renée Blake discusses how she relates to students when teaching African American English linguistics and the battle that takes place in reversing systematized stereotypes.

“The biggest misconception people have of African American people is who African Americans are. I actually don’t think it’s about language. It’s about people,” she said.

The panelists spoke to the audience about their own experiences, expanding but also challenging some elements of the film.

“Growing up in the Bronx, ‘ill’ was a word we used a lot,” said UMass’ Associate Chancellor for Equity and Inclusion, Anna Branch. She began to speak about her appreciation of switching her speech between a relaxed environment and a working environment, which was a component touched on in the film where often times speech was changed depending on the environment people found themselves in. Branch also questioned tensions that exist for Students of Color. While there may be cultural appreciation for the language in popular culture, that same language may not provide access in professional settings.

“There are so many things to think about,” Branch said to the audience, explaining that there are many interwoven complexities involved.

In Green’s interview in the film, she gave the audience questions to think about regarding the expectation of African Americans to perform within their speech, and if the associations of certain phrases are what it means to “talk Black.” She brought up the point of contact, questioning the line of African American English on one hand and White American English on the other. She said that the film underscored how children’s speech and language develops over time.

Journalism professor Nick McBride told the audience about his love of the First Amendment and blues music, before explaining the long history of African Americans in this country and their continual fight for their music and also a voice.

“Rap is the grandchild of this tradition … fighting the power,” said McBride. “Without African American speech and identity, we have no America.”

The panel then opened up to questions from the audience, covering white commodification of hip-hop, the film’s purpose, the role linguistics play in education, how certain structures are reinforced as “right” without much challenge and the perceived “language of opportunity.”

“There’s so many ways of communication. It’s about power and systematic oppression,” said Carlos McBride, who spoke from the audience explaining that we not only speak through our words, but through how we walk or how we shake someone’s hand. “We’re in a day and age when we are led by a violent administration; language is really important right now,” he said.

Ocean Eversley, BDIC in communications and African-American studies major, said she could not imagine a blues song or jazz song without the sound of black voices. She added that she cannot say that academic English is necessarily superior to the wisdom of black ten-year-olds in the Bronx.

“Listen to what people have to say and value its substance,” she said.

Email Caeli Chesin at mchesin@umass.edu or follow her on Twitter @caeli_chesin.