“Back to the Woods” Taylor Swift and the New Trend of Rugged Authenticity

On her new album, Taylor Swift debuts a much more muted, insular sound, but it may just be the next step in the evolution of modern pop.

On July 24th, Taylor Swift surprise-released a new album, titled folklore. The greyscale cover featured the young pop star standing in a forest, dressed in a plaid coat and prairie dress, dwarfed by trees. The woodsy aesthetic seems intentional: Swift’s last few albums featured more frequent dalliances with genres like hip hop and EDM, ironic for an artist whose entree to the pop culture zeitgeist was a country tune titled “Teardrops on My Guitar.” folklore, on the other hand, features a much more muted sound, focusing more heavily on the singer-songwriter aspect of her music, with much more sparse instrumentation. While the sudden pivot was nearly as surprising as the release, it actually puts her in line with other latter-day pop singer-songwriters.

In the mid-2010s, both Justin Timberlake and John Mayer suddenly moved to the Midwest—in each case, specifically to Montana, with Mayer buying a secluded ranch outside Bozeman, and Timberlake buying a house in the prestigious Yellowstone Club, an ultra-exclusive part-club-part-ski-resort in Big Sky, with combined entrance and membership fees of over $300,000. For Timberlake, it was in addition to his Los Angeles home, while for Mayer, it involved selling residences in both LA and New York. The moves came at relatively opportune times in each artist’s life—for Mayer, after a series of fairly controversial statements in magazine interviews (including one for Playboy, which the Washington Post described as “cuckoo-racist”), and for Timberlake, after the worst album reviews of his career so far, as well as some controversies over general social tone-deafness.

And in each case, the respective changes of scenery achieved the same result: new albums, with new musical themes and aesthetics befitting their new surroundings.

On January 2, 2018, Timberlake released a minute-long trailer on YouTube teasing his upcoming album, Man of the Woods, which he claimed was inspired “more so than any other album I’ve written, [by] where I’m from.” The video features Timberlake sprinting through a corn field, brooding in a pasture, dancing around a campfire, etc., dressed outdoorsily throughout. The album, released the following month, featured tracks with titles such as “Flannel,” “Montana,” and “Livin’ Off the Land;” its cover featured a straight-on shot of Timberlake, roughly bisected on a diagonal, giving the appearance that a pro-quality photo of the artist in a blazer was being torn away to reveal a faded Polaroid of his real self underneath, bedecked in jeans and flannel.

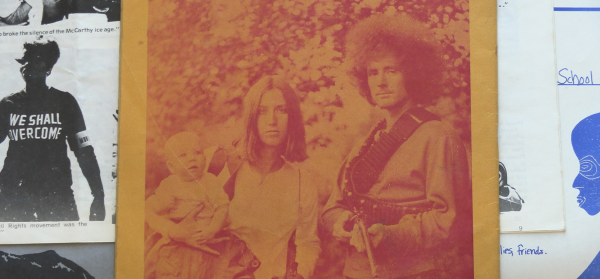

Similarly, Mayer adopted an entirely new aesthetic himself: where once his public style could probably be reliably categorized as “fratty slacker,” post-Montana move, he went full Western: shoulder-length hair, nondescript jacket, and Stetson hat, in every public appearance. And while Mayer was never a stranger to blues riffs or the guitar, the music he created in isolation eschewed the smooth, adult contemporary pop that had become his stock-in-trade, in favor of a much more roots-rock sound, focusing largely on acoustic guitars and harmonica.

However, these returns-to-nature and aesthetic shifts show the cracks in their respective facades fairly plainly. Timberlake, of course, is from Tennessee, but hardly “of the woods”: at age 12, he and his mother moved to Orlando so that he could appear on The New Mickey Mouse Club show, and by age 14, he was a member of *NSYNC. Mayer, who titled his first heartland rock album Born and Raised, was himself born and raised in—respectively—Bridgeport and Fairfield, Connecticut.

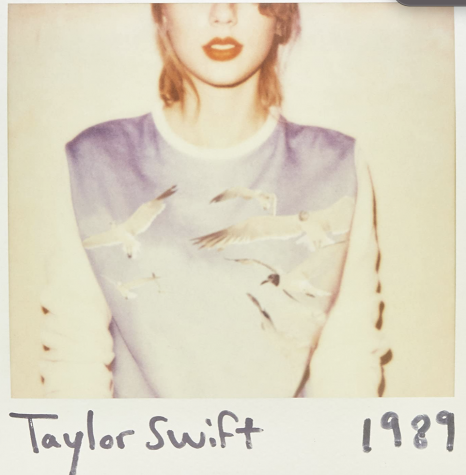

More than either of them, though, Swift has a more tangible grasp on the subject matter: despite not coming from humble origins herself—her father is a Merrill Lynch financial adviser—Swift got her start in the country music scene while living in Nashville. She later made the transition to straightforward pop around the time of 2014’s 1989, with further explorations into synth and electronica on the albums that followed, but at her core, she has a closer connection to autobiographical folk music than either of the aforementioned men: Timberlake’s career started in bubblegum pop and transitioned into R&B with a hip hop flavor; and while Mayer may have started with earnest acoustic confessionals, his first album, Room for Squares, already relied more heavily on the jazzy soft rock for which he would become most well known.

What, then, took Swift in such a disparate direction with folklore? Applying the same logic as with Timberlake and Mayer, what is Swift escaping? Perhaps a perceived lack of authenticity—the word “inauthentic” has cropped up in reviews of her music as far back as 2012’s Red. Perhaps it was a response to the criticism she received for staying silent on political issues for so long, even among writers who simultaneously admitted that she had no “duty…at all…to voice a political opinion.”

More likely, though, it seems that it was prompted by the same crisis we have all experienced: COVID-19. In announcing the album on Twitter, Swift mentioned that it was written and recorded entirely “in isolation.” After canceling all of her 2020 concert dates and sheltering in place, she allowed her “imagination [to] run wild.” The difference shows in the results: left with only her thoughts, the songs she wrote are much more introspective than her usual fare. Gone are the triumphalist kiss-offs and defiant post-break-up anthems of “Shake It Off” or “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together;” in their place are contemplative second-guesses, that a former love may actually have been “the 1,” or admitting fault in a toxic relationship in “this is me trying.” Her songs have always been extremely personal, even leading to song-by-song speculations about which song was about which former beau, but this album feels much more mature and contemplative, taking the long view by considering the past and future, rather than simply the present. Songs on folklore even make explicit reference to songs on previous albums, as if rethinking prior feelings.

Past even her usual creative topics, Swift incorporated genuine storytelling into her repertoire: in the album’s announcement, she explained that she ended up writing songs not only about herself and her own experiences, but also “from the perspective of people I’ve never met, people I’ve known, or those I wish I hadn’t.” In the past, she occasionally delved into stories about third parties—2008’s “Love Story,” for instance—but typically, they were stand-ins for Swift herself. With folklore, however, Taylor expands her songwriting palette by writing songs about completely disparate characters—a love triangle which recurs across multiple songs, a biographical tale about the life of beleaguered Standard Oil heiress-by-marriage Rebekah Harkness.

Albums made among isolation are not new, of course: even Swift’s collaborator on folklore’s “exile,” Justin Vernon of Bon Iver, wrote that band’s first album while sequestered in a hunting cabin deathly ill with an infection. Even writing and recording during a pandemic is not specific to Swift: Tyga released an unofficial quarantine anthem of sorts, the obnoxious-cum-infectious “Bored in the House,” in March, and Charli XCX recorded this year’s how i’m feeling now entirely from her home studio. But for Swift, solitude led to a period of creative rumination, which she clearly felt paired best with music that matched the lyrics’ contemplative tone. In some ways, it may seem odd or disingenuous to suddenly get sincere by going “back to the woods”—the way songsters of the 1990s feigned artistry simply by going “unplugged.” In reality, as John Mayer and Justin Timberlake have shown, this is simply another step in the evolution of the modern pop singer-songwriter.

Email Joe Lancaster at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter @JoeRLancaster