The Elephant in the Room: Tiger parenting and Asian American suicide

Racially motivated violence and high expectations are detrimental stressors for Asian Americans

Racially motivated acts of violence towards Asian Americans have been at the forefront of the media recently. A study released by the Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino states that Anti-Asian hate crimes have increased by 149% in 16 of America’s largest cities, spiking in March and April of last year when the coronavirus pandemic was still in its early stages. However, an overlooked racially motivated cause of violence in Asian Americans, even before the spike in hate crimes, is suicide most likely caused by discrimination or a harsh style of parenting.

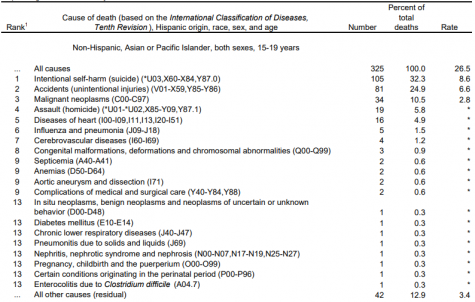

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states that in 2018, intentional self-harm (suicide) is the leading cause of death in Asian Americans age 15-24. This cause of death does not lead for any other group of people.

Even in Asian Americans age 25-34, suicide is the second-leading cause of death.

This begs the question: why?

The American Psychological Association states that Asian Americans that were born in the United States are at a higher risk for mental illness due to cultural clashes between American culture and Asian culture instilled by elders.

Being of Filipino descent while living in Los Angeles where practically half of my friend group has Asian backgrounds, I witnessed “Tiger Parenting” both first-hand and second-hand.

Tiger Parenting is defined as a form of strict parenting where parents push their children to high standards. This usually means attaining high levels in academics and high levels in “sophisticated” extracurriculars such as music. Oftentimes, these Tiger Parents believe that continuous criticism and a focus on their children’s shortcomings will motivate their children to fix their flaws.

However, licensed therapist John M. Kim said in an article he wrote for Psychology Today that Tiger Parenting often leads to two after-effects: anxiety and depression. The anxiety arises from fear of not being good enough in the future; the depression arises from being discouraged based on past failures.

“They want their children to succeed and live a happy life,” Kim said in his article. “But it is a happy life as they have defined it based on the culture they have grown up in.”

Kim encourages parents to incorporate more positive-based motivation into their relationship with their children. All children should live a life feeling joy as opposed to living a life full of fear of disappointing others.

This cycle of Tiger Parenting is difficult to stop. Even if a child is okay with this form of parenting, they might adapt it for when they have children of their own and continue the cycle.

Many people are empathetic towards others that have experienced this harsh style of parenting. In fact, a subreddit called “r/AsianParentStories” has a community of almost 60,000 people who share their (bad) stories of Asian parenting.

As I skimmed through the plethora of posts on the subreddit, I noticed two things. One is that almost every post talked about the disheartening aftermath of the disapproval from these kinds of parents. The second is that even if parents are supportive of their children’s lifestyle or decisions, that child still feared the possibility of disappointing their parents because of prior experiences.

Someone I know who wishes to remain anonymous, and is of Filipino descent, was recently kicked out of his house during the pandemic by his parents because he changed his major from nursing to financial analysis. In Filipino culture, children are almost always “encouraged” to become a nurse. STAT reports that 4% of all nurses in the United States are Filipino. This might not sound like much, but to put into perspective, 20% of all nurses in California are Filipino. Although my friend has figured out a housing situation for himself, he still has not returned back to his original home or even contacted his parents since the incident. He is still struggling mentally, but he has declined all of our suggestions to seek professional help.

Although my own parents are supportive of what I do now, it wasn’t always like that and I felt that same fear of disappointment. Many of my own friends suggested therapy to which I agreed to eventually, but reluctantly. I was intimidated mainly because I thought that going to a therapist wasn’t normal. But eventually, something clicked.

I was watching “BoJack Horseman” and I heard a humorous yet inspiring joke that went something like:

How many therapists does it take to change a lightbulb?

Usually only one, but only if the lightbulb wants to change.

Yes, I know that it sounds crazy that a show about a talking anthropomorphic horse changed my views on therapy, but it is valid and I think the joke makes a good point.

However, for many Asian Americans, wanting to change and fighting the stigma behind therapy is not the only obstacle. According to the American Psychological Association, Asian Americans need culturally tailored care. The article states that one in two Asian Americans suffering from mental illness will not seek assistance because of language barriers. Additionally, a study in 2002 cites that only 2.3% of 90,000 doctoral-level psychologists are of Asian descent, adding to the difficulty of a language barrier. Hopefully, in the future, more people of Asian descent will aspire to be psychologists to fill in this gap.

Information about this is rare. According to PhD candidate Amelia Noor-Oshiro, there has just been one national study conducted on Asian American mental health. That study conducted by the Massachusetts General Research Institute dates back to the early 2000s. The Asian population in America has increased by 72% since the study was conducted. Therefore, a newer study is much more warranted now with the larger population and observations may have also changed since then.

The numbers cited by the CDC date back to 2018, so experts are not fully aware of how the coronavirus pandemic and the rise in Asian hate crimes have affected the data.

“Communities of color also have trouble accessing mental health treatment, so we don’t know how these groups — Black, Latinx, Asian, and Indigenous Americans — will be affected [by the pandemic],” psychologist Rhonda Boyd said in an article by the Philadelphia Inquirer. “Hopefully more data will come out and we’ll get a better picture.”

Although I discussed Asian Americans and Tiger Parenting, everyone’s struggles with mental health are valid regardless of race or cause. A psychology professor I talked to once said “It’s good to tune up your car once in a while; it’s good to tune up your brain and seek professional help once in a while as well.” For those of you that are struggling mentally, I highly suggest seeking professional help.

Here is a list of resources that I recommend you look into if you are struggling mentally:

The national suicide hotline prevention lifeline is (800) 273-8255.

The Center for Counseling and Psychological Health (CCPH) has a variety of mental health resources and counseling, ranging from individual therapy sessions as well as group sessions. They have crisis services, call the 24-hour hotline at (413) 545-0800.

Clinical and Support Options (CSO), a group of behavioral health and substance abuse services with outpatient locations in the state. Walk-ins are encouraged and the closest walk-in center to the UMass Amherst campus would be the Northampton location. Their number is (413) 582-0471.

Resources outside of the UMass and Five College community can be hard and stressful to find. The following links including Psychology Today and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMHSA), can help you find mental health resources near you.

Email Aaron at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter @WhatTheFacundo