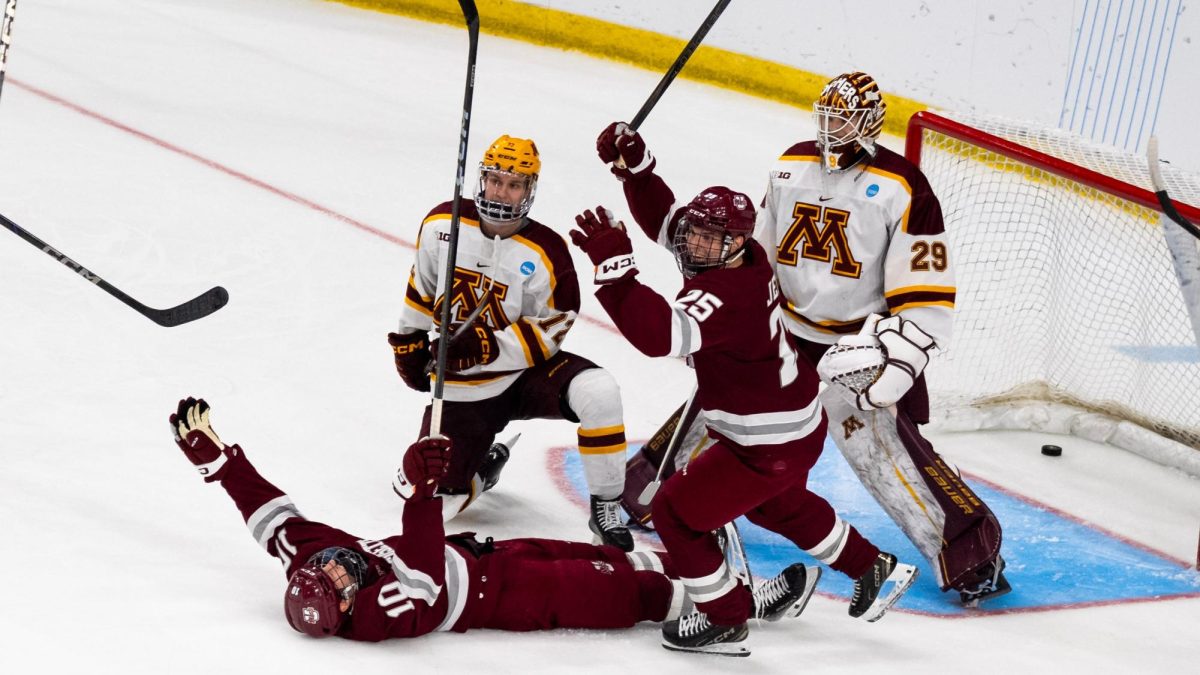

During an NCAA Tournament Game on Mar. 24 between USC and Mississippi State, one of the brightest and most talented players in the country and USC’s star guard, Juju Watkins, suffered a devastating ACL tear that will sideline her for the offseason and most of the upcoming season.

This highlights a significant issue in women’s sports today. These injuries come from a gap in funding, research and support for female athletes. Female athletes competing in collegiate or professional basketball are two to eight times more likely to suffer ACL injuries than male athletes are.

The lengthy recovery periods they have to endure limit their opportunities to become successful athletes and reach their full potential. The disparity in injury rates between men and women is well-documented and researched. Still, Scott Myrick, the Assistant Athletic Trainer for the UMass Women’s Basketball team, emphasized that it is not a simple issue.

“They’ve looked at differences between females and males, everything from bone structure to the way females are built, to hormonal cycles,” said Myrick. “But there hasn’t been any one particular thing that stands out as being the end-all-be-all.”

The absence of the current Big Ten Player of the Year in the following games caused the school to see a notable drop in attendance, which dropped by 30%, and television ratings, which dropped by 22%. Watkins is part of the new generation of women’s basketball players, which includes popular athletes such as Caitlin Clark, Angel Reese, and Paige Bueckers. This injury is also a major blow to her future draft stock and her chances to cement her name in women’s professional basketball.

“[ACL injuries] are easily one of the most common injuries that we see,” said Myrick. “If you’re at the college level, you could easily anticipate seeing one or two every one to two years, and that wouldn’t be unusual.”

The trainer also pointed out that while UMass has made significant investments in women’s basketball injury prevention and research, the same can’t be said for every school.

“The resources here, the facilities that we have, do a really top-notch job as far as I’m concerned, of giving us what we need to work with the female athletes, to take care of them, to help prevent injuries,” he explained. “I’ve been in other institutions, so I feel like this really is better than other places that I’ve been.”

Across many athletic programs at colleges in the U.S., there is still a significant gap in funding and research for injury treatment, and a lack of support for female athletes, especially when compared to male athletes. Female athletes, on average, have shorter careers and aren’t given the same opportunity to develop and showcase their abilities at the highest level.

Just six percent of all strength and conditioning research is based on women, and less than 34 percent of all sports medicine journals have ever published the results of studies that included women.” This limits the advancement of effective training and recovery protocols, as the research isn’t made to tailor towards women. Female athletes often receive treatment that doesn’t meet their needs, increasing both the risk of initial injury and future injuries.

One of the major talking points within sports is that female athletes don’t deserve the same level of respect as they are not as talented as male athletes, but this overlooks a major factor: women’s sports don’t see nearly as much investment on a national level. The disproportionate way in which funds are poured into men’s athletics at the collegiate and professional levels leaves women’s sports at a disadvantage. All this does is reinforce the stereotype that women’s sports are less valuable, which reflects broader gender disparities in athletics.