On October 16th, the UMass Museum of Contemporary Art hosted a reception to celebrate the unveiling of Tammy Nguyen’s new exhibit, “The Political Uses of Madness.” The Connecticut-based artist and current Wesleyan University professor drew direct inspiration from Daniel Ellsberg’s lecture on nuclear war policy of the same name.

Invited by UMass to go through the Ellsberg archives, Nguyen transformed anti-nuclear materials from the eclectic whistleblower and activist into a dissonant, yet harmonious exhibit of abstract artworks.

Ellsberg, who donated his voluminous archive to UMass in 2019 before his death in 2023, is best known for his disclosure of the Pentagon Papers, a massive study on the Vietnam war by the RAND Corporation, where he was an employee. By leaking the papers to the press and exposing over a decade of lies by the U.S. government, Ellsberg risked prison time and kicked off a dramatic struggle between press freedom and government secrecy.

What is less known about Ellsberg, though, is his commitment to anti-nuclear activism, which was spurred by his proximity to nuclear war planning during his time at RAND. His peek behind the curtain of America’s nuclear capabilities terrified him. He wrote and spoke extensively about its dangers, leaving behind a paper trail that now resides on the 24th floor of the DuBois library.

Nguyen’s exhibit brings those archival materials to life.

It features nine paintings done on paper and stretched over circular wooden panels, a reference to the nine rings of hell from Dante’s Inferno. The entire space is soundtracked by a turntable playing a record of a Vietnamese woman and Ellsberg singing a capella.

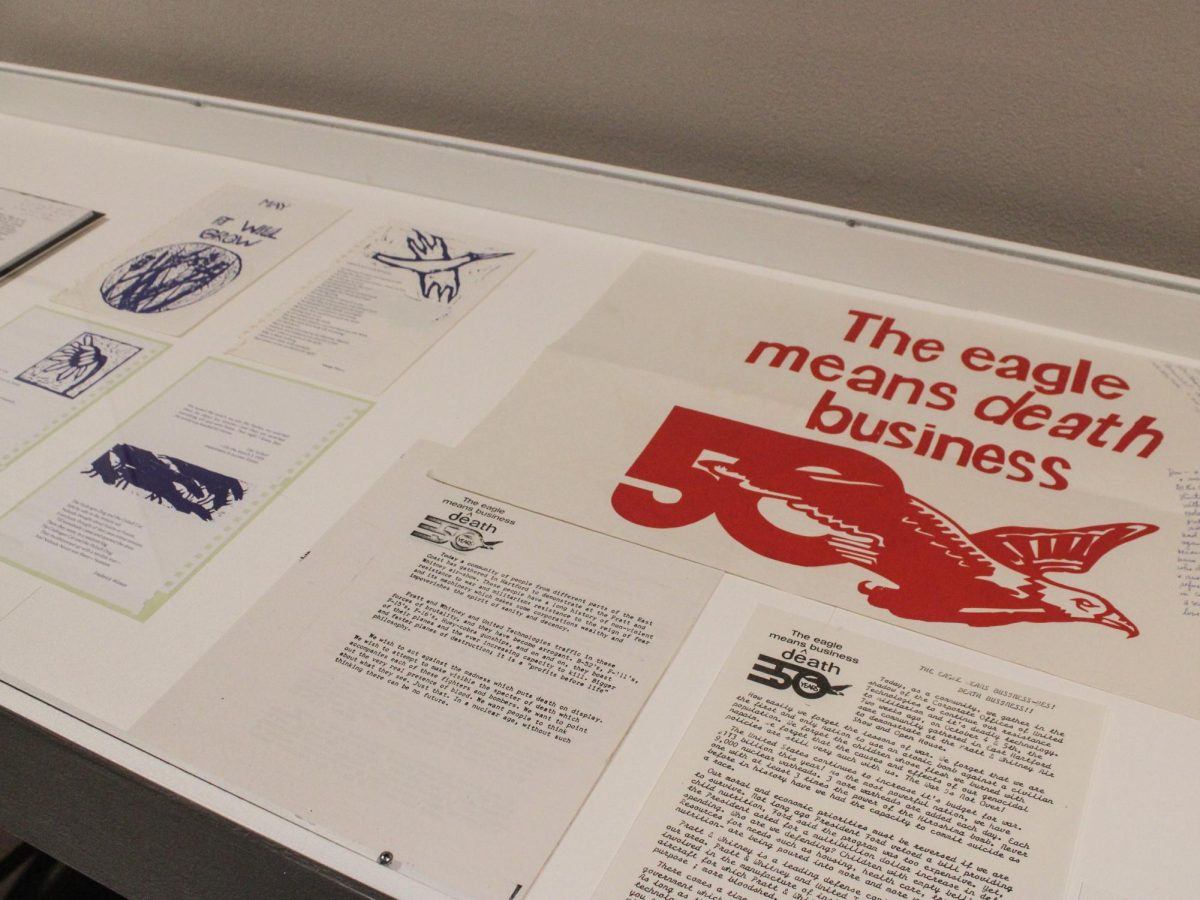

At opposite ends of the exhibit sit two glass cases. In one lies pages from It Will Grow, an anti-war poetry collection, decorated with illustrations similar to an illuminated manuscript. These pages inspired four of Nguyen’s paintings. Also in the case were books, Vietnam war protest materials, and a page from the manuscript of the Ellsberg lecture, all found in the archives. The other case features specimens from the UMass Herbarium, derived from the many motifs of wheatgrass and daisies found throughout the collection. “I need vegetation. I need madness,” said Nguyen.

A multimedia artist, she used other techniques aside from painting to create a chaotic look of madness in her art. Nguyen utilized hot stamping and rubber stamping. Half of the stamps she created herself by drawing up the initial design on a computer before turning it into a brass tool that can be heated up and hot-stamped into metal foils. Her use of water-based materials like calligraphy ink and watercolor was an intentional choice to create a more meticulous look, allowing her to fully immerse herself in the details. The paintings also feature words and quotes from Ellsberg’s essays that are woven throughout the art like cobwebs.

Nguyen says the north star of her work is the concept of a symphonic space, like a forest rich with biodiversity, where the viewer feels welcomed to observe. “There’s an invitation for you to suspend yourself in this imaginative space that borrows from a lot of disparate histories put together.” Each painting in the exhibit is derived from different but interlinked anti-nuclear stories, poetry, art, and documents from the archives, which she describes as “Easter eggs.”

The driving inspiration for the exhibit came from Nguyen’s Vietnamese heritage. The daughter of two Vietnam War refugees, Nguyen credits the Vietnam War for shaping much of her life and upbringing. To her, the heart of being an artist is figuring out “Who am I? Why am I the way that I am?”

Growing up, Nguyen’s father worked closely with journalists as a translator in Saigon. She says he was enamored by figures like Ellsberg after he disclosed the Pentagon Papers. As a child, Ellsberg was like a “cartoon of justice” to Nguyen.

In his lectures on “The Political Uses of Madness,” Ellsberg explores the idea of leaders using “madness” (in this case, the threat of nuclear warfare) as a geopolitical strategy. Nguyen was drawn to the lecture for its provocativeness, and the way it had pieced together grand political theories with concerns of everyday people “who find themselves as one person on a planet dealing with nuclear threat.”

Nguyen’s favorite painting from the exhibit was Vera B. Williams, a portrait of the children’s writer who was also a nuclear disarmament activist during her lifetime. As a child, she would read Williams’ book, A Chair for My Mother, every day with her father. When sifting through the Ellsberg archives, she happened upon a copy of Williams’ poem, Parents, adorned with a drawing of a daisy. Nguyen was moved upon realizing the connection. The painting was an appropriation of a different portrait of Williams from the Black Mountain College, where she created art and poetry for the nuclear disarmament cause.

Contending with the ideas of madness, Nguyen found herself confused and unsure of what to make of Ellsberg. She describes herself as a person of a diaspora, and speaks to the challenges of being in-between groups of friends, generations, and histories. Because of this, she says the act of having convictions can become difficult. As for Ellsberg, her admiration of him comes from this very in-between, ambiguous space, “He’s a man of strong convictions. Yet his interests were far-fetched, contradictory, extremely nuanced, and multi-layered,” says Nguyen.

The “Political Uses of Madness” exhibit will be housed at the UMass Museum of Contemporary Art until May 8th, 2026.