In 2019, artist John C. Anderson, driving and listening to an NPR broadcast on global warming, heard a broadcaster say that over 3 billion birds, or around 30% of the bird population, had died over the past half-century, in part due to environmental encroachment. Shocked, he pulled over to listen closely to the broadcast and ensure that his ears were not deceiving him. To his dismay, the words he had heard were true.

“So I just had been thinking about, how do I make a piece about this?” Anderson said. “It was so compelling. I just went back to my studio.”

Using wood, rubber, steel, and paint, Anderson realized his vision over the course of about six months. The final product, “Tell Me When the Last Bird Sings,” features hand-painted birds within clock-like frames that vary in size, each one tethered to a hook by strips of bicycle tire.

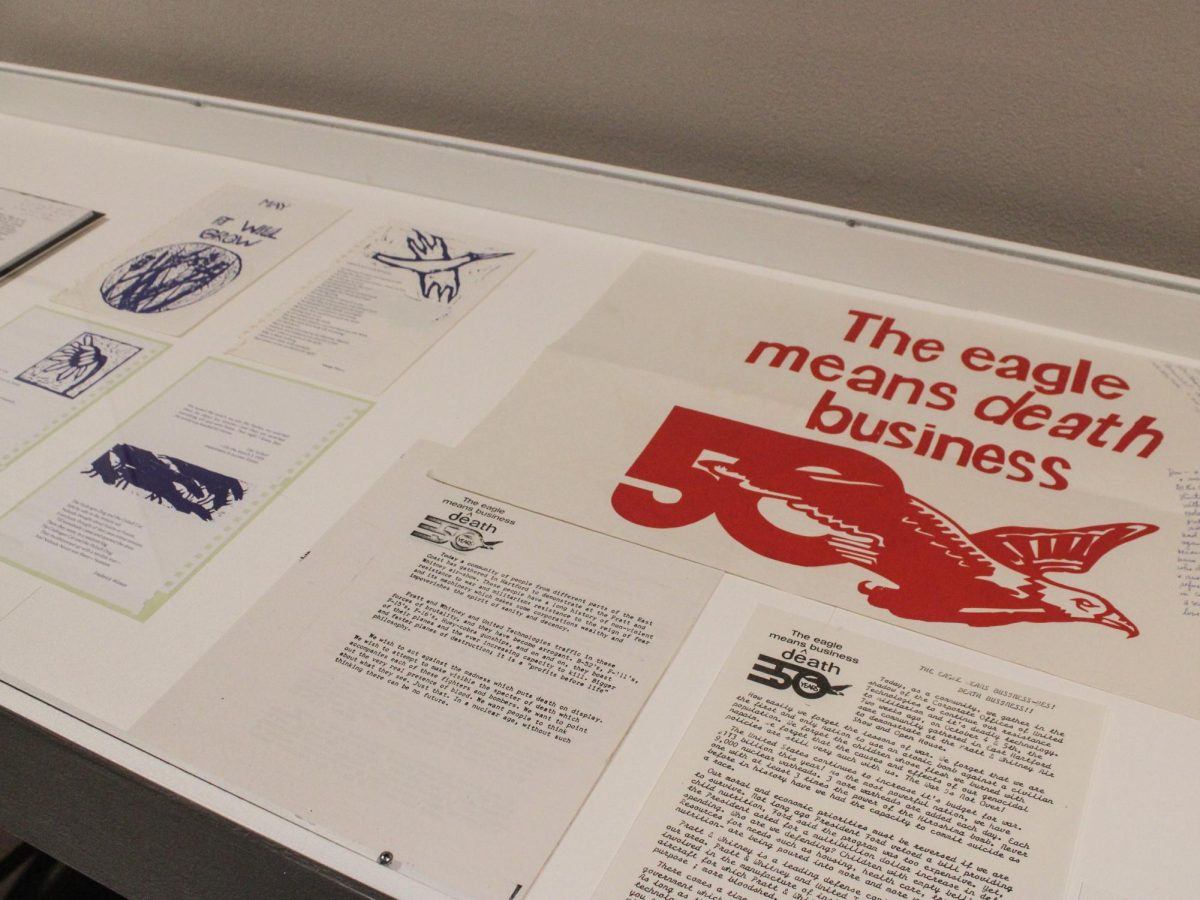

This piece is one of 50 showcased at the Hampden Gallery’s first triennial, entitled “Reflecting on the Past / Dreaming the Future.” The exhibit features the works of 37 artists living or working within 50 miles of the University of Massachusetts Amherst campus.

The landmark triennial is part of the Hampden Gallery’s 50th anniversary celebration, a milestone that honors the gallery’s past while also looking to the future. But to the artists who organized and participated in the event, its relevance goes beyond just an anniversary.

Nick Capasso, the exhibit’s juror and director of the Fitchburg Art Museum, explained that though human beings are always pitted between the past and future, “there is probably a little more urgency to our awareness of that balance because things seem to be changing at a very rapid rate,” he said, alluding to America’s fraught political landscape.

Anderson invites viewers to think about this rapid change in “Tell Me When the Last Bird Sings.”

The artist studied ornithology texts and taught himself how to paint in the early stages of the project, taking cues from his wife, a fellow painter.

The strips of bicycle tire are visibly stretched, and, as Anderson put it, “it should feel when you’re looking at it like they could snap; they could fall apart at some point. Maybe not in our lifetime, but it’s not going to be there forever.”

Additionally, some of the birds are hidden by clock frames, which may initially be frustrating to audiences. However, Anderson hopes these viewers will then ask themselves: “If this is frustrating, how does it feel knowing that real birds are vanishing from the planet?”

Political and environmental themes are present throughout Anderson’s work, and he says his projects are usually animated by a cause dear to him, “because I’m a human being living on the planet.”

Susan Montgomery is another artist whose works, “Flypaper Killers” and “Purveyor of Poison,” are featured in the triennial.

Both projects are part of Montgomery’s “Poison” series, which features female protagonists who were associated with, accused or convicted of poisoning.

The two women presented front and center in “Flypaper Killers” are Margaret Higgins and Catherine Flannagan, Irish sisters convicted of poisoning Higgins’ husband by contaminating his tea water with flypaper, which used to be made with arsenic.

Higgins and Flannagan were subsequently executed, but, considering factors like the era’s sexism and lack of medical knowledge, it is very possible that the sisters were actually innocent.

Moreover, “Purveyor of Poison” displays a female wallpaper seller wearing a dress made of wallpaper samples, a common method women used to sell those particular wares.

Other artifacts of poisonous products surround the woman, including a teapot made with toxic glaze, a dead mouse killed by arsenic, and a portrait of William Morris, a textile designer and leader of the arts and crafts movement.

Despite Morris’ insistence that arsenic posed no harm to people, the volatile chemical was poisoning those who worked with his products, like the woman in the painting.

To create these works, Montgomery started with drawing and gradually added light layers of watercolor. However, creating watercolor pieces on such large scales was challenging, and Montgomery would often employ the help of her husband or children to move her work from the wall to the floor or table.

“I felt like it just matched up perfectly because of my interest in history and women’s stories,” she said. “This unveiling, and then the sense of doing them now and feeling like they’re reclaiming, showing women’s agency now in this little bit of a revenge way.”

Through her artistic process, Montgomery was able to capture the histories of Higgins, Flannagan, and the wallpaper seller within her works and reveal their stories anew from the lens of the present.

Other pieces of her work will be available at the Augusta Savage Gallery in an exhibition that features watercolor pieces by both Montgomery and the late UMass Amherst professor Richard Yarde, Montgomery’s former teacher. It opens on Nov. 14 at 5 p.m. and runs through Feb. 26.

Montgomery and Anderson are only two of the many artists whose work is on display at the Hampden Gallery Triennial. The main gallery is on view until Dec. 3, and the Incubator Project Space is open through May 8, 2026. Other mediums showcased at the exhibition include paper collage, oil, acrylic yarn, mushroom spores, and video installations.

Capasso hopes that as viewers walk through the gallery, “it would stimulate thought about both the past and the present.” With such a wide variety of styles and mediums, artists say the Hampden Gallery Triennial encapsulates the creative energy of the region.

Max Della Fera can be reached at mdellafera@umass.edu