The town of Amherst – what’s in a name?

In Amherst, the town itself isn’t the only thing named after a controversial commander.

Portrait of Lord Jeffrey Amherst.

AMHERST ─ Otherwise a quaint town in western Massachusetts, Amherst is home to 28,000 college students—many of whom are unfamiliar with the origins of their new surroundings.

Tucked away in the midst of farmlands, Amherst has gained worldwide recognition as a top-tier town for higher education. Nonetheless, people rarely ask the simple question: Where does the town’s name come from?

Jeffrey Amherst was born in England in 1717. For the majority of his life, Amherst served as a successful military commander for the British, leading troops in Canada and North America before serving as commander-in-chief of the British army on two separate expeditions. He held positions such as Governor of Quebec and Crown Governor of Virginia, and was eventually named a Lord.

But this decorated war hero image may mask a disturbing ideology when it comes to the French and Indian War.

In order to deal with hostile Native Americans, Amherst advocated for a sinister alternative to physical fighting; he wanted to gift blankets contaminated with smallpox to local tribes. It is believed by many that this heinous crime wiped out dozens of Native Americans.

Although historians argue whether or not Amherst followed through with the plan, one thing is for certain: a British trader did gift a tribe smallpox-infected pieces, a practice approved by the British military. Although this fails to prove a direct connection between Amherst and infected blankets, it likely led to a rampant outbreak of smallpox among the Natives in the Ohio Valley.

There is no solid proof that Amherst followed through with this plan, but his disregard for natives at the time is noted.

“You will do well to try to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, as well as to try every other method that can serve to extirpate this execrable race,” Amherst wrote in a 1763 letter.

In 1759, before he had even become a Lord, a small town in western Mass. was named for him. In 1958, the Amherst Historical Society stated that when the town was named, Amherst was “the most glamorous military hero in the New World. … …the name was so obvious in 1759 as to be almost inevitable.”

Today, citizens in the United States frequently question the sensibility of honoring historical figures with a dark past. Many people believe that by altering statues, names or other long-standing monuments, history is being erased. Opponents of these monuments believe that honoring controversial figures, such as Confederate generals, is disrespectful.

The tension can develop into violence, as shown by the 2017 white supremacy rally in Charlottesville, VA. which resulted in the death of a young woman. The rally was protesting the removal of a Robert E. Lee statue in town.

Statue of Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, Virginia.

In Amherst, the town itself isn’t the only thing named after the commander. Both the prestigious liberal arts college in town and the commonwealth’s flagship campus bear his name.

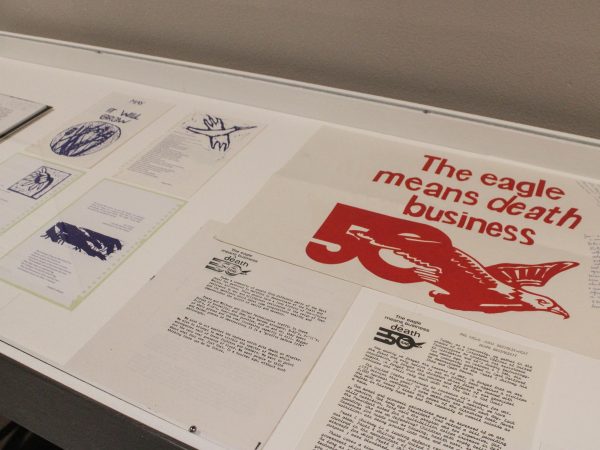

Just two years ago, Amherst College dropped its unofficial mascot “Lord Jeff,” drawing national attention. After protests and campus forums — and despite backlash from alumni — the students succeeded in their goal to eradicate Lord Jeff from campus, and the school adopted the Mammoth to replace it.

Amherst College is not the first school to change a controversial mascot. In 1972, after a group of Native Americans complained about the UMass’ Redmen mascot, the university switched to the Minutemen.

UMass mascot Sam the Minuteman.

Four high schools in the area still maintain Native American imagery in mascots, names, or logos. Efforts led by high school students to change offensive names often lead to disappointment. For instance, students at Amesbury High School have attempted to change their name, the Indians, and their mascot, a Native American, to no avail. Agawam High School students have also attempted to change their logo depicting a Native American, but were unsuccessful.

Unlike many high schools, higher education has embraced the change. Thanks to a push by Native American activist groups, the NCAA singled out 31 colleges with racially-charged mascots in 2005. The organization issued a self-evaluation of team imagery to ensure that offensive language and mascots would not be used any longer. Included on this list was nearby Merrimack College. To conform to the new standards, Merrimack kept their Warriors name but changed the former Native American chief logo to a Trojan warrior logo.

Many local colleges changed mascots prior to the NCAA’s policy. Springfield College’s sports teams, once the Chiefs, adopted the Pride as their mascot in 1997. UMass Lowell’s teams, also previously the Chiefs, have been the River Hawks since 1991. Dartmouth College, formerly the Indians, replaced their mascot with the Big Green in 1969.

There will always be two sides to the argument of changing names; those that want to keep tradition, and those that want to create a comfortable and inclusive environment for all. In situations such as Amherst, the wrongdoings of the commander are blurry, but his intentions were clear enough to change the mascot. Changing the town name, however, would likely require more concrete evidence.

In regard to mascot names such as the Indians, Chiefs or Redskins, these situations are much easier to solve. With names rooted directly in oppression, racism and violence, the connotation that these names carry is harmful to Native Americans today. These names are more likely to be overturned than the Lord Jeffs, due to the concrete evidence of their derogatory origin. But Native American activist groups will tirelessly fight for respect until every derogatory mascot is expelled. There is no doubt that even in the 21st century, these arguments will continue to divide people for years to come.

Email Matt at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter @MattBerg33.

"Three words: Vice President Oprah." -Obama

Email Matt at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter @mattberg33