UMass Dining: the price of being “number one”

Food insecurity is a growing issue on college campuses.

(Patrick Kline/Amherst Wire)

“What are people without meal plans doing for food?”

“Where can I find extra money to afford food?”

These are questions being asked by Cornell University students in a GroupMe thread called ‘The Whole Community,’ a place where undergraduates can ask questions and discuss their issues. Food insecurity is a growing issue on college campuses, and with rising costs of tuition and living expenses, these questions are becoming more difficult to answer.

The Department of Agriculture defines food insecurity as a state in which “consistent access to adequate food is limited by a lack of money and other resources at times during the year.”

UMass Hunger and Homelessness Campaign Coordinator Jonathan Lee said organizations such as MASSPIRG, The Center for Education Policy and Advocacy (CEPA), and Alpha Phi Omega (APO) have been more focused on redirecting wasted food and making sure it becomes food for students in need.

“To alleviate food and toiletry insecurity for students, we run donation drives, supply closet drives, and we’re the main organization on campus that makes sure the Dean of Student Affairs toiletry supply closets are filled, as well as donating foods to CEPA and APO for their packaged meal plans,” Lee said.

However, with the University of Massachusetts raising the prices of meal plans for the coming semester, low-income students are having difficulty affording the most basic meal plan, ‘DC Basic’, which costs $2,779.

“Even affording that is unbelievably expensive,” Lee said.

“It’s obviously going to affect low-income students, but the Food Access Coalition’s plan is that we make a consistent, scheduled solution for students, so they don’t go hungry on campus and make sure there are always resources for them to come and get food.”

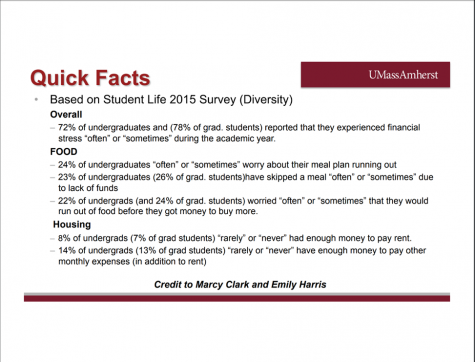

According to the 2015 Student Life Survey, 24 percent of UMass undergraduates “often” or “sometimes” worry about their meal plan running out.

Programs such as The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which is the largest program in the domestic hunger safety net according to the USDA, are beneficial to eligible low-income individuals and families because it offers them nutritional assistance.

But having such a large program can hurt eligible residents rather than help them. According to Mass. Legal Services, Massachusetts ‘SNAP Gap’ is the difference between the number of low-income Massachusetts residents receiving MassHealth who are likely SNAP-eligible and the number of people receiving SNAP. In Massachusetts, the size of this gap is currently about 680,000 people.

Quality of food can also vary. In 2018, the Food Bank of Western Massachusetts provided 9,682,097 meals. However, 44 percent of that food was canned goods, bread and cereals, while only 29 percent was fresh fruits or vegetables. This lack of nutrient-dense foods can lead to diet-related diseases like obesity and diabetes.

In the 2007-2008 school year, the price for room and board at UMass Amherst was $7,478. In the 2018-2019 school year, it costs $12,626, a whopping price rise of nearly 100 percent in just ten years. It’s not surprising that students can’t afford pricy meal plans.

Even Ivy League schools are affected by food insecurity. Gloria Coicou, founder of the Healthcare Students Association at Cornell, created an initiative called ‘Mobile Bread and Butter Food Pantry’, which provides free food to students to address food insecurity and food waste on campus.

“The food pantry is open to everyone whether you have a need or not. I want it to be a stigma-free area and be comfortable with taking part in it,” Coicou said. “Cornell students may look like they don’t need help or have the financial security to afford food, but that’s not the case. The need is there.”

There are several long-term initiatives universities and communities can invest in, including home gardens, sustainable agriculture and increasing agricultural biodiversity. According to the USDA, for every dollar spent on seeds and fertilizer, home gardeners can grow an average of $25 worth of produce.

To feed a growing population, large corporations began using genetically modified organisms (GMOs) to meet the high demand for food, which degrades the environment, rely on fossil fuels and use large quantities of pesticides and fertilizers. Studies involving small farms have shown that decreasing pesticide usage can increase yield by up to 42 percent.

UMass Dining was unable to be reached after multiple requests for comment.

Reach Harry at hortof@umass.edu.

Email Harry at hortof@umass.edu, or follow him on Twitter @HarryOrtof

"I walk, I look, I see, I stop, I photograph." - Leon Levinstein

Email Patrick at pkline@umass.edu and follow him on Twitter at paterickkline