Almost 50 years later, the Pentagon Papers are still significant

Daniel Ellsberg set the precedent for leaked documents to be published by the press.

The New York Times report that John Bolton’s unpublished manuscript revealed President Donald Trump withheld $391 million in aid to Ukraine unless they investigated the Biden family and other Democrats is the most significant revelation in Trump’s impeachment trial so far.

“Over dozens of pages, Mr. Bolton described how the Ukraine affair unfolded over several months until he departed the White House in September,” the article states. “He described not only the president’s private disparagement of Ukraine but also new details about senior cabinet officials who have publicly tried to sidestep involvement.”

There was another point in American history when thousands, not dozens of pages led to one of the most important Supreme Court cases in American history and the impeachment process against former President Richard Nixon—the Pentagon Papers.

By 1971, the Vietnam War had been taking place for 16 years with no end in sight. The National Archives estimates that 58,220 US soldiers lost their lives during the American occupancy, while over 500,000 Vietnamese civilians were killed.

(Christopher Michel/Wikimedia Commons)

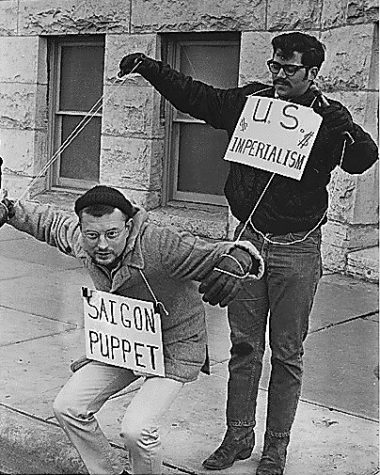

The war was immensely unpopular in the US—anti-war protests were widespread throughout the country, and tensions ran high. On May 4, 1970, four Kent State University students were killed after the Ohio National Guard fired into a crowd of students.

In 1967, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara began to try and answer the question on everyone’s mind—what was the US doing in Vietnam? McNamara gathered a team of experts and analysts to study government archives, dubbing the top-secret project the Pentagon Papers. One of the men hired to work on this project was a former marine with a PhD from Harvard: Daniel Ellsberg.

Ellsberg worked at the Rand Corporation, a think tank that researches public policies for private and public agencies. One of their clients at the time was the Defense Department. Initially, Ellsberg was a “hawk,” someone who was very pro-war. But after reading the papers in their entirety, Ellsberg changed his view on the war and became a “dove,” someone who is anti-war.

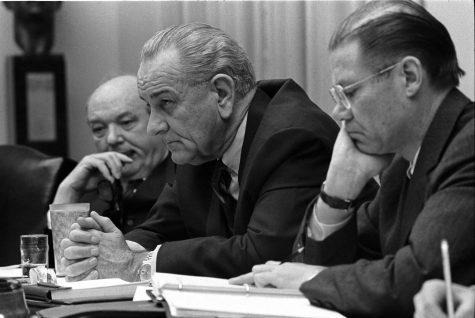

The Pentagon Papers found that four different presidents—Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson—had lied to the American people about the state of the war in Vietnam.

Despite their access to an immense amount of data showing the US’s goals in Vietnam were not being reached, these administrations chose to tell the American people the US was succeeding. In 1969, Ellsberg decided he needed to expose their lies.

But there was a problem. Ellsberg didn’t have the legal authority to publish these documents, meaning he could be charged with treason if he was caught. Furthermore, only 15 copies of the report existed—someone was bound to notice if one went missing.

To avoid getting caught, Ellsberg created a system—at the end of each workday, he’d cram as many pieces of the 7,000-page report he could fit into his briefcase and walk over to a friends advertising agency. There he would painstakingly photocopy each piece of paper one at a time, then return the documents to Rand in the morning. It took Ellsberg more than a year to finish photocopying the entire report.

(Yoichi Okamoto/Wikimedia Commons)

Ellsberg’s initial plan was to use congressional immunity to publicize the report; members of Congress are exempt from arrests for treason, breach of the peace or felonies. Ellsberg contacted four Senators— Chair of the Foreign Relations Committee J. William Fullbright, George McGovern, Mike Gravel and Charles Mathias. All four of them declined. Rather than give up, Ellsberg went to the only institution with the prestige, manpower and legacy to publish these documents. The New York Times.

Neil Sheehan, former Saigon bureau chief for the United Press International was the perfect man for the job—the anti-war articles he wrote for the Times demonstrated this to Ellsberg. The two met at Sheehan’s home in Washington to discuss the report. Ellsberg even gave Sheehan a key to his apartment in Cambridge so he could take notes on the report.

But Sheehan and his wife Susan went one step further, taking a piece of the study from Ellsberg’s apartment to a copy shop and creating a duplicate without Ellsberg’s knowledge. Ellsberg was out of harms way—all the liability was now on Sheehan and the Times.

However, before the report could be printed, Sheehan needed to convince the Times managing editor A.M. “Abe” Rosenthal to publicize it. Although Rosenthal was a hawk, he decided to publish the documents because of their significance. Rosenthal sent 75 Times reporters, editors and other staff to a Hotel Hilton in midtown Manhattan to begin working on “Project X.”

(W.Wolny/Wikimedia Commons)

On June 13, 1971, the Times published the first of three excerpts from the Pentagon Papers. The headline read, “Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement.” The day after, Attorney General John Mitchell orders the Times to cease further publication of the documents, citing “irreparable injury to the defense interests of the United States.”

After declining this request, the Department of Justice sues the Times for a temporary restraining order to halt further publication. Judge Murray Gurfein grants the DOJ their request—the Times couldn’t publish any more documents until the case is decided in court.

Meanwhile, at the Washington Post, editor Ben Bradlee had read the Times report and immediately set upon getting his own copy of the Pentagon Papers. With the injunction seeming like it would doom his plans, Ellsberg contacted a Post editor he knew named Ben Bagdikian and gave him a copy of the Pentagon Papers. The Times had taken three months to analyze the documents—the Post had just over 12 hours.

The stakes for the Post were much higher than the Times; the Post’s lawyers vehemently argued against publishing, knowing a federal court had just issued a restraining order against the Times. Second, Post executives were worried the chair of the FCC, which was controlled by the Nixon administration, wouldn’t renew their broadcasting licenses. Furthermore, the Post Company was planning to go public; if the publisher, Katherine Graham, were charged with a felony, investors would back out of the deal, which would cause the Post to go bankrupt.

(Harris & Ewing/Wikimedia Commons)

Despite all these risks, Graham decided to publish the documents. On June 18, 1971, the Post headline read “Documents Reveal U.S. Effort In ’54 to Delay Viet Election.” The DOJ immediately sued for another restraining order but were denied their request by Judge Gerhard Gesell. Meanwhile, Ellsberg had sent the Pentagon Papers to several other prominent newspapers, including the Boston Globe and the Christian Science Monitor.

On June 19, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. circuit voted to uphold Judge Gessell’s injunction, which he denies again. However, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reverses Judge Gurfein’s decision to deny the injunction.

On June 26, the two cases were combined and expedited to the Supreme Court, where the case became known as New York Times Co. v. United States. On June 28, the Grand Jury in Los Angeles charged Ellsberg and his co-conspirator Anthony Russo with theft and espionage. Ellsberg surrenders to the FBI and admits his role as the whistleblower.

On June 30, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that the US government didn’t sufficiently prove the leaked documents were an immediate threat to national security. The Pentagon Papers could continue to be published—in his opinion, Justice Hugo Black stated “the Framers of the First Amendment, fully aware of both the need to defend a new nation and the abuses of the English and Colonial governments, sought to give this new society strength and security by providing that freedom of speech, press, religion, and assembly should not be abridged.”

In May of 1973, Judge Matthew Byrne dismissed Ellsberg and Russo’s case after learning the Nixon administration had hired “plumbers” to break into Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office to find negative information about him.

So, why are the Pentagon Papers relevant today? Because it established an important precedent for the press—unless the documents presented an immediate danger to national security, newspapers could publish leaks they feel are newsworthy. Second, it shows the power of checks and balances; while the executive branch sought to keep the Times and the Post from publishing the Pentagon Papers, the judicial branch overruled him.

Regardless of what Trump’s lawyers say, John Bolton and the American people have the First Amendment on their side.

Email Harry at [email protected] or follow him on twitter @HarryOrtof.

Email Harry at [email protected], or follow him on Twitter @HarryOrtof