How does the Electoral College actually work?

The electoral college is a system that dates back to the beginning of US history that we still use to this day

With election night over and votes still set to be counted and recounted, it is easy to get confused about how United States elections work. Although many of your favorite news stations have projected a winner for the election, voting and counting do not end on election night, but rather on Dec. 14 through a system called the electoral college.

The election is not decided by the amount of votes a presidential candidate gets, known as the “popular vote.” It is instead decided by electors, or representatives states choose to cast their votes. This process comes from the Constitution, as a compromise between a vote only in Congress, and a popular vote. In the 1700s and early 1800s, the candidate with the most votes would become President, and the second most votes became Vice President. The 12th amendment was added to make it so there were two separate votes for President and Vice President.

So have any of these procedures changed up to the present day? Not really. Now, when you go to the polls and cast your vote, you are still not deciding who will become president. Instead, you are telling electors from your state who you think should be president, and they get to decide. The amount of electors each state receives is based on the Census, with one elector for each senator and representative, and three electors representing the District of Columbia. A candidate must get at least 270 electoral votes out of 538 to win. All states, besides Maine and Nebraska, give all of their votes in a winner-take-all system to the candidate receiving the most votes. Maine and Nebraska appoint an elector for each Congressional district, and the other two electoral votes are decided by the popular vote. 29 states, as well as the District of Columbia, have laws requiring electors to pick the president-elect by the popular vote. Some electors over the years have violated their state’s laws binding them to the popular vote, but not many.

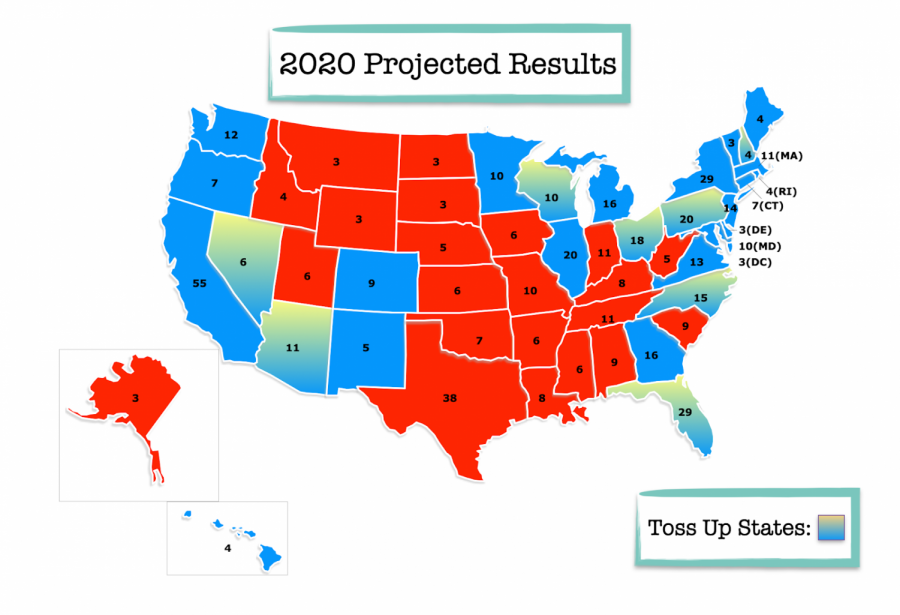

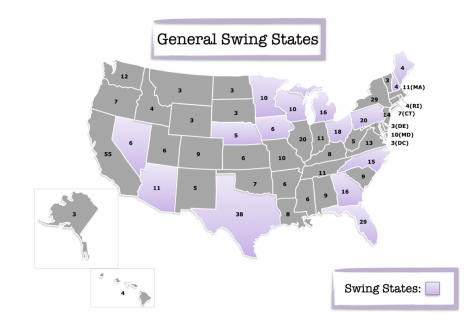

A lot of states make similar voting decisions from year to year, like Massachusetts usually voting Democratic, or Texas usually voting Republican. There are a handful of states which vary enough each election day, considered swing or battleground states. These are states where the winner could take votes by a slim margin, so they are sometimes contested. Some places usually considered swing states are Florida, North Carolina and Nevada. During this year’s election, states to watch were very unlikely ones with places like Georgia, which usually voted red, voting a majority blue. This made the results of the projected election very different than pollsters could have guessed.

This year, the schedule for when the electoral college starts to make decisions begins after election day, in December. Any election disputes have to first be resolved by Dec. 8, which includes any recounts and court cases contesting the election. On Dec. 14, electors meet in each state where they cast votes and send them off to various people. These people include the president of the Senate who is the Vice President of the U.S. and the secretary of state. By Dec. 23, ballots must be received by the president of the Senate. On Jan. 6, votes are counted, and on Jan. 20 the president-elect will finally become the president of the United States.

All of this information applies to this year’s election in a few ways. First, while people have complained about not finding out who will be president on election day, the reality is we do not actually find out until over a month after. This trend of knowing who would become president on election night was actually started by broadcast networks in the 20th century. We may know the popular vote and a projection of who the winner is, but until the electoral college votes, we do not truly have a president-elect.

The other way the electoral college applies to this year’s election is through lawsuits. This has been one of the most contested elections since Bush v. Gore in 2000 and the Trump team has many lawsuits in court. The electoral timeline states must be resolved by is Dec. 8, meaning they only have roughly two more weeks to resolve the lawsuits. The Trump team and the Republican Party have currently brought around 18 lawsuits, of which they have had two decisions upheld, eight rejected or denied, and eight pending in the courts. The first upheld decision was for the separation of mail-in ballots in the state of Pennsylvania. The second upheld decision was a request for voting locations in Nevada to be kept open later, of which they stayed open until 8 p.m. Most of the pending cases are stated to have no legal basis for the claims.

Email Talya [email protected] or follow her on Twitter @TorresTalya