The value of space: Reviewing Glenn Kaino in Mass MoCA

A peak into the curation of Mass MoCA’s immersive exhibit

About thirty people wait patiently on the stairs overlooking Building 5 at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art in North Adams. Soft, instrumental music plays as overhead lights flicker and shift, stirring shadows in the distance. A museum attendant gives the signal to move ahead, and the line stands and walks toward the installation. Together, viewers move through light and shadow, taking a journey through time and space in Glenn Kaino’s immersive artwork entitled “In the Light of a Shadow.”

Kaino’s installation, which opened at Mass MoCA in April and will remain on view until September 5, 2022, stuns visually through its vastness. The installation expands over three exhibits with a collection of multi-media artworks; the first exhibit houses found objects hanging underneath a boat made of wooden fragments, the second features a projected video accompanying a metal cylindrical sculpture, and the third exhibit holds tropical plants growing from hollowed rocks adjacent to two cloud chambers — machines that allow viewers to see electrically charged particles.

The multi-faceted works bluntly invoke themes of collective action, yet without the guided curation and wall texts typical of most juried exhibits, the collection exudes chaos. Without the curator, the primary message becomes convoluted as the installation targets two divergent events in history: the past protests of Selma, Alabama from 1965 and the 1972 protests of Derry, Northern Ireland. The two events relate only through their shared historical labels of “Bloody Sunday”; otherwise, their connection stirs confusion.

However, like the balance of light and shadow, the dynamic between Kaino and Denise Markonish, Mass MoCA’s senior curator and director of exhibitions, work harmoniously. Kaino’s vision becomes aptly articulated through Markonish’s curation of space, resulting in a visually stunning multimedia exhibit that reminds viewers of all what they missed in art museums during the pandemic.

Upon entering the main exhibit, a small room foreshadows the installation with carved fragments of wood with various inscriptions, such as “We Can’t Breathe” and “Worker’s Rights,” emblazoned on the front panel. The wooden panels, situated on canvas, form an arrow pointing toward the adjacent wall, where fragments with additional inscriptions are on fire. Flames flicker behind a wooden fragment that states, “We shall overcome.”

In the football-field sized gallery space of Building 5, a dismantled sculptural boat appears to emerge from the center of the ceiling. As if time has suddenly stopped, accompanying fragments of wood and stone surround the sculpture, creating an illusion of an abrupt explosion hanging overhead. Below, a lighted pathway allows viewers to walk underneath the sculpture while strobe lights shine behind the hanging objects, projecting shadows of crosses, ships, rocks, and human figures on the walls. Viewers may momentarily be reminded of Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” as the shadows reflected on the wall become the visitor’s present reality.

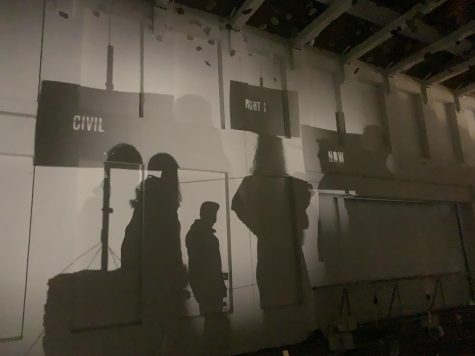

Near the end of the installation, viewers stop at the end of the walkway near a mirrored cutout of Ireland’s Free Derry Wall, which forces them to view their own reflections. Lights suddenly flash on the participants, and viewers are met with their reflection again, but this time through their shadowed silhouettes on the wall. Protests signs are reflected above the visitors’ shadows with messages of “Civil Rights Now” and “Climate Action” signaling worldwide protests and a need for universal participation.

As viewers turn around, the suspended boat forms an ouroboros, a serpent eating its own tail, igniting symbolism of the cyclical nature of protests and revolution throughout history. The music stops, and the lights brighten, allowing for a closer inspection of the hanging objects. The shadowed ships are made of rock with postcards from Selma, Alabama as the ship’s sails.

But even after the flashing lights, projected shadows, and the soundtrack, the connection between the protests of Selma and Derry remains ambiguous. Without reading the entry wall text, viewers will likely not recognize the historical events or their relationship to each other. The combination of protest signs at the end of the walkway with messages like “Climate Action” further muddles the artwork’s intent. While the exhibit clearly denotes the power of social action, the spotlight on Selma and Derry seems oddly specific and lacks the note of universality the artist seemingly hopes to project. Yet through the following exhibit, Kaino’s artwork and Markonish’s curatorial focus on transitional space guide the reader to a clearer understanding of the installation’s meaning.

Visitors exit through an adjacent exhibit that houses a circular jail complete with metal bars. Footage from the May 29, 2020 peaceful Black Lives Matter protests in Los Angeles are projected onto a blank wall across the jail. Viewers watch live footage of Deon Jones, a member of Kaino’s studio, attempt to leave the protest and then get shot with a rubber bullet by police. The video transitions to photos of Jones’ hospital visit where he received stitches. After the hospital photos, the footage shifts again, and the art performance begins. Jones sings a rendition of U2’s “Sunday Bloody Sunday” as he stands inside Kaino’s sculptural jail. In between clips of Jones’ singing, the video flashes from protests in Selma to protests in Derry.

When the film ends, visitors can circulate the jail, hitting the metal bars with force, which plays notes from the U2 song; the audience participates in a physical action, igniting a musical response. Both video and sculpture work in tandem: After watching the projected clips of the Black Lives Matter protest, witnessing the recorded violence of the police’s rubber bullets, and then physically hitting the metal bars to initiate the notes of the song, the viewer becomes apart of the artwork. As visitors circulate the jail, banging out a musical note, it becomes difficult to separate the U2 lyrics from the recent political events: “I can’t believe the news today, oh, I can’t close my eyes and make it go away.” Kaino successfully creates an emotional connection for the participant, while further highlighting the need for unity.

Through this adjacent exhibit, viewers are brought to the present through the events of the past year. The peaceful protests for George Floyd, the rubber bullets shot by the police, and the ongoing revolutions for justice and equality align with the past events of Selma and Derry. The transitional space of the gallery allows viewers to navigate the artwork, creating context and providing clarity.

The last exhibit requires visitors to climb stairs to the upper mezzanine, which overlooks Building 5’s large gallery space. The center of the room holds a platform of growing plants nestled in hollowed rocks, while the adjacent wall houses the two cloud chambers, each of which contain a rock. The chambers, used to detect ionising particles, allow viewers to witness the movement of electrically charged particles coming off the rocks they hold.

The accumulation of plants and visible particles signify growth, new perspectives, and ultimately, a sense of hope. Overlooking the suspended ouroboros, the viewer is reminded of the cyclical nature of history, connecting the protests of the past to the present; Selma and Derry no longer seem like a distant memory.

Although it’s a fantastic spectacle, the immense detail found in Kaino’s work overwhelms viewers through chaotic thinking. Yet, the careful curation of Markonish and the use of transitional rooms hone Kaino’s voice, articulating meaning through the museum’s physical space. As Markonish bridges the gap between artist and viewer, the relationship between artist and curator strengthens, creating a unique, multisensory experience that can only be enjoyed in person.

Email Chelsea Staub at cstaub@umass.edu, or follow her on Twitter @chelaucar

"Whether you succeed or not is irrelevant, there is no such thing. Making your unknown known is the important thing--and keeping the unknown always beyond...