Birds of prey, including a falcon and an eagle, were showcased at the W.E.B. Du Bois Library on Friday by Tom Ricardi, a wildlife biologist and licensed animal rehabilitator.

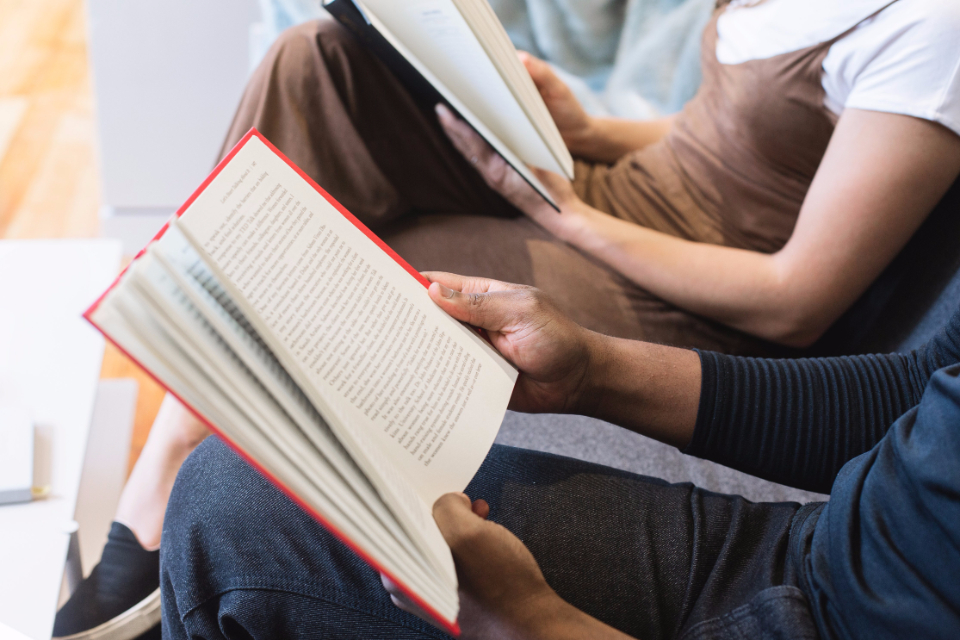

The homecoming event, held in the lower level of the library, amassed a standing-room-only crowd of students, alumni, university staff and local community members. Some lined the railings of the descending staircases to get a better view.

Ricardi stood at the front of the crowd. Behind him were five travelling crates of varying sizes. A few audience members guessed what bird was in each.

A majority of the audience was UMass students. Lexie Thomas, an animal science major, hoped this experience would broaden her knowledge of birds, which she has limited personal experience with.

“I’m excited to see the animals up close, and to talk to someone who works with them personally, because they likely have a greater knowledge than our professors just telling us things,” Thomas said.

Ricardi, a former environmental police officer of 38 years, is the owner and operator of the Birds of Prey Rehabilitation Center, located at his home in Conway. He cares for dozens of birds of prey, all of whom have suffered injuries.

“I have a project that I’ve been working on for many years, and it’s rescuing, rehabilitating, and releasing back to the wild birds of prey,” Ricardi said.

One student decided to come based on their own experience with animal care. Bella Dame, an animal science major, works for a reptile rehabilitation center. She was looking forward to seeing the difference in Ricardi’s work compared to reptiles.

Others, like Echo Munoz, a sustainable food and farming major, were drawn to the event due to their interest in birds.

“I am a birder outside of school hours,” said Munoz. “Whenever there’s a bird event, I decide to attend it if it’s in my free time.”

One by one, Ricardi brought out the raptors: a black vulture, a barred owl, a northern saw-whet owl, a peregrine falcon and a golden eagle. The audience fawned and gasped for each one, many taking out their phones for pictures.

“I’d like to make a really special point to young people. These are not my pets. I don’t name them. I think it’s a disservice to wildlife,” Ricardi said.

He explained that none of these raptors could be released back into the wild, as they had sustained permanent injuries that impacted their survival skills. The black vulture, for instance, was rescued by the public works department in Springfield. They were knocking a building down, and falling debris hit the bird, injuring its wing beyond repair.

This past year has been busy, according to Ricardi. He has received a lot of birds afflicted by rodent poisons, including the barred owl.

“[Poisioned rodents] are like a living mouse trap,” Ricardi said.

When a rodent is poisoned, they can live for several days after. Now an easier target, when birds eat the prey, they can suffer secondary effects of rodenticide, sometimes even to lethal levels, according to the National Audubon Society.

These aren’t the only threats to birds of prey. “We’ve got a lot of birds here in New England that are on the state-threatened list because of habitat loss,” Ricardi said. “We’re losing a lot of birds as days go by.”

Ricardi warned that human infrastructure and technology cause a lot of bird injuries. Birds fly into windmills and cellphone towers, or they confuse solar panels as bodies of water.

Moreover, birds fly into windows, unaware of their presence until they make contact. Ricardi has rescued two peregrine falcons this year that have flown into windows.

According to Ricardi, birds also fly into the sides of cars as they hunt for prey. He explained that birds are often near highways because people litter. They throw food out of their windows, which attracts rodents and eventually birds.

“Unfortunately, wildlife is the last thing to be considered,” he said.

For his last bird, Ricardi brought out a golden eagle. The bird appeared comfortable with Ricardi, alternating between spreading his wings wide and nuzzling against the rehabilitator.

About 15 years ago, a woman called Ricardi, and she said there was a brown bird stuck on a power line with a broken wing. The golden eagle’s wing was shattered, and it couldn’t heal properly. The eagle has been with Ricardi since.

“People say to me, what a great hobby you have. Let me tell you, it’s 24/7,” Ricardi said. “And if I’m going to do a job, I’m going to do it the right way. So when that phone rings, if it’s important enough for a person to call, I answer the call and go out and rescue the bird.”

Police officers across western Massachusetts contact Ricardi if they encounter an injured bird while on patrol. Ricardi also collaborates with local animal control and MassWildlife, the state government’s division of fisheries and wildlife.

“If you find a young bird, best advice, leave them alone. If they are injured, call [MassWildlife]. Get a hold of rehab or a rehabilitator and check that bird,” he said.

As a child, Ricardi shared that the first thing he would do each morning is go outside and look for birds. He said that he’s always loved wildlife, a passion he accredited to his fourth grade teacher, who came to class each day with binoculars around her neck. She worked with birds.

Beyond the work he does in Conway, Ricardi holds birds of prey programs across the region. Lauren Hubbard, associate editor of digital content for UMass Libraries, arranged the program with Ricardi after the university asked them to host an event related to the peregrine falcons nesting on the library’s rooftop. Their nest is livestreamed on Youtube, which is extremely popular on and off campus, according to Hubbard.

“I immediately thought of Tom Ricardi, because he’s such an engaging speaker, and what better way to learn about raptors than to see them up close and personal,” Hubbard said.

This isn’t Ricardi’s first time at UMass. According to Hubbard, he’s been here in 2015, 2016, 2021 and 2022.