How prescription opioids helped fuel the Massachusetts heroin epidemic

Rob Lelacheur of Milford was prescribed OxyContin in the 12th grade after breaking his ankle. He had no idea at the time that this would mark the beginning of a long-term battle with opioid addiction that nearly took his life.

Lelacheur trusted his doctor. He took his dose as directed.

When the prescription was cut off, he began to go through withdrawal. Seeking relief, he turned to a friend who bought him loose prescription pills from the streets.

“Whatever he put on the table, it made me feel better,” Lelacheur said. “Because I was a full-blown opiate addict in withdrawal.”

Eventually, Lelacheur began buying loose pills for himself.

“By the time I knew what was happening to me, it was already too late,” he said.

Lelacheur is one of thousands of opioid addicts in Massachusetts whose struggle began with a prescription.

The opioid epidemic

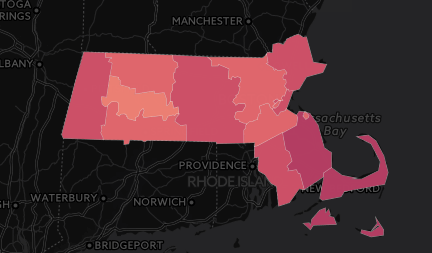

Fatal opioid overdoses have skyrocketed in every county in Massachusetts since 2000.

According to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH), 355 people in Massachusetts died because of an opioid overdose in 2000, or 5.6 for every 100,000. By 2015, that number jumped nearly fivefold to 1,747, or 25.8 for every 100,000 people.

State leaders have taken notice. Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker called the issue an “epidemic” that has touched nearly every corner of the commonwealth.

Amherst is not exempt. In 2014, a 20-year-old student at the University of Massachusetts Amherst was found dead from a heroin overdose. In 2015, 17 Hampshire county residents died as a result of an opioid overdose, according to the state’s DPH.

Massachusetts is not alone. According to the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), deaths attributed to opioid overdoses have dramatically increased nationally since the late 1990s and early 2000s. As of September 2016, opioid overdoses are responsible for an estimated 30,000 deaths per year, nationally.

Driven by prescriptions

While just 10 percent of fatal opioid overdoses in Massachusetts in 2016 were attributed to prescription opioids such as OxyContin, OxyCodone, Percocet and Vicodin, according to the Massachusetts DPH, prescription opioids have played a major role in fueling the broader opioid epidemic.

These prescriptions have become more common over the past two decades as pharmaceutical companies have pushed drugs to treat both acute and chronic pain. Before the 1996 release of OxyContin by Purdue Pharma L.P., opioid prescriptions were rare and reserved for extreme conditions like cancer.

The boom in opioid abuse across the country has coincided with the rise of prescription painkillers in the late 1990s.

In Massachusetts alone, the number of opioid prescriptions rose from just over 1 million in 1996 to over 4.5 million in 2013, according to the DPH’s Prescription Monitoring Program.

A 2015 report from ASAM points out that, “from 1999 to 2008, overdose death rates, sales, and substance use disorder treatment admissions related to prescription pain relievers increased in parallel.”

The ASAM report found that “the overdose death rate in 2008 was nearly four times the 1999 rate; sales of prescription pain relievers in 2010 were four times those in 1999, and the substance use disorder treatment admission rate in 2009 was six times the 1999 rate.”

Purdue argued in 1999 that less than one percent of patients who are prescribed opioids become addicted. But recent studies have cast serious doubt on that figure.

Like Lelacheur, many of the people prescribed an opioid by their physician — 23 percent, according to ASAM — develop an addiction.

Roughly three in four heroin users nationwide began their abuse with a prescription opioid, according to a New York Times report.

Massachusetts State Rep. Carole Fiola, who represents Fall River, one of the state’s hardest hit towns, said she believes prescription opioids are the most significant factor contributing to the opioid epidemic.

“There are a lot of factors that are contributing to [the epidemic], but the number one factor we see is that a lot of people got hooked on ‘properly prescribed’ pain medication…who then turned to heroin when they couldn’t get access to it anymore,” she said.

“In my core group of friends that I have in recovery … 10 out of 10 of us had all started with pharmaceuticals,” Lelacheur said.

‘One day, they just cut me off’

When Lelacheur first began using his prescription painkillers, he wasn’t aware of how dangerous they were.

“One day, they just cut me off,” he said. “When they cut me off, I think I had my first case of withdrawal. Even though I didn’t know what it was.”

Before he knew it, Lelacheur — then in his early 20s — was doing anything he could to get opioids through any avenue necessary. He stole money from his parents and sold his possessions in order to buy pills from street dealers.

Eventually, like in the case of so many other Americans, he began to turn to street heroin — a cheaper and more potent alternative.

But street heroin is even more dangerous than prescription pills, and many users are willing to jeopardize their lives in order to satisfy their addictions.

Reducing prescriptions

As experts discover more evidence about the dangers of prescription painkillers, many states, including Massachusetts, have begun to take steps to curtail their influence.

In 2012, Massachusetts legislators passed a bill that made it mandatory for all physicians to enroll in the state’s Prescription Monitoring Program. More recently, the state’s legislature passed a bill in 2016 limiting first-time opioid prescriptions to a seven-day supply.

Earlier this year, state legislators also expanded opioid abuse education requirements for public schools in an effort to increase awareness of the dangers associated with them.

These regulations, along with increased awareness among physicians, have helped lower the number of opioids being prescribed. Between 2013 and 2016, the rate of opioid prescriptions in Massachusetts fell dramatically, from 11.1 percent of all residents to 4.9 percent, according to the state’s Prescription Monitoring Program.

Critics, however, argue that such regulations, while well-intended, may cause even more problems in the short term as more people begin using heroin after their prescription is cut off.

In 2014, over 30 percent of all opioid overdoses were attributed to prescription painkillers in Massachusetts. By 2016, that figure fell to about 10 percent. However, total deaths caused by opioids have only increased in that time. Between 2014 and 2015, opioid deaths rose from 20 per 100,000 people in Massachusetts to 25.8. By September of 2016, more people had overdosed on an opioid than in all of 2015, according to state estimates.

Heroin is often more potent and more lethal than prescription pills since its production is unregulated. Street heroin is increasingly cut with fentanyl, an opioid that can be 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine and can be extremely dangerous. The drug’s potency can also change from batch to batch, without the user knowing.

Deaths attributed to fentanyl have increased considerably in recent years. In 2014, roughly 30 percent of all opioid overdoses in Massachusetts were attributed to fentanyl. In 2016, that figure exceeded 60 percent, according to the state’s DPH.

A new beginning

While Lelacheur takes personal responsibility for what happened to him, he says he was not warned by his doctor about just how dangerous opioid dependency can be.

Recovery was a daunting prospect for Lelacheur, in part because of the stigma surrounding addiction.

“I was definitely ashamed,” he said.

People were quick to judge — to assume he had bad parents or was a bad person, which wasn’t the case.

“It wasn’t who I was,” said Lelacheur. “Just because I was a heroin addict doesn’t mean that I wasn’t a human being.”

But Lelacheur knew he was getting in too deep.

“I knew that if I didn’t do something about it, I was either going to end up in prison or dead, within a short period of time,” said Lelacheur.

After years of struggling with addiction, Lelacheur decided it was time to seek treatment. He found a support group. Though it wasn’t easy, Lelacheur got sober.

Recently, Lelacheur tore his MCL at work. Despite his history of drug abuse, his doctor still wrote him an opioid prescription.

“I went in, and after telling them that I am a recovering alcoholic and heroin addict, the first thing he did was write me a prescription for Percocets,” he said.

Lelacheur refused the prescription. “That little white pill will kill me — it will take my mother’s son, it will take my sister’s brother, my niece’s uncle,” he told his doctor.

Pain relief alternatives can be costly, time-consuming and typically less effective in the short term than prescription opioids are. Because alternatives are less convenient, Lelacheur believes doctors are too quick to prescribe “the magic pill,” and move on to their next patient.

When Lelacheur was first prescribed an opioid, he was too young to realize the potential danger. His doctor thought the pills were necessary, so he trusted the decision.

“I definitely think I was prescribed a pill that I didn’t need,” he said.

Lelacheur believes that overprescribing opioids and the stigma around addiction create a vicious cycle for addicts.

To people suffering from addiction, Lelacheur offers this advice: “Ask for help, there are plenty of people out there who aren’t going to judge you.”

Lelacheur stressed that addiction can happen to anyone.

“It doesn’t matter where you are from or how you were raised — and I’m a perfect example of that,” he said. “It’s taking actually normal people and turning them into actual monsters.”

If you or someone you know is suffering from addiction, call the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (SAMHSA) hotline at 1-800-662-HELP, or find treatment at https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov/.

Email Bryan Bowman at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter @BryanBowman14.

Email Nicole Defeudis at [email protected].

Email Jacqueline Pollock at [email protected].

"One day or day one. You decide."

Email Nicole at [email protected], or follow her on Twitter @Nicole_DeFeudis