UMass vs. Goliath: How can universities keep marginalized students in STEM?

With dwindling retention rates for students of color in the College of Natural Sciences and abysmal rates for women in the College of Information and Computer Sciences, how does the UMass administration respond?

Dr. Gilda Barabino, center in the blue green jacket, posing with University of Massachusetts Amherst faculty and staff. (Julia Donohue/ Amherst Wire)

AMHERST– At the University of Massachusetts, faculty and staff gathered in March to launch the ADVANCE program. After introductions, City College of New York Dean Dr. Gilda Barabino, a recipient of the President Medal of Science, electrified the crowd with personal anecdotes of her accomplishments in the STEM field.

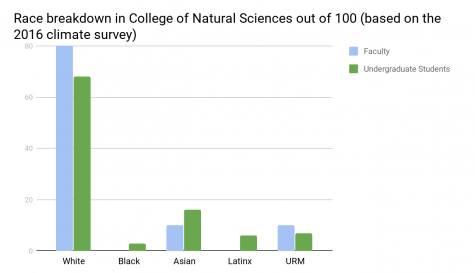

The ADVANCE Institutional Transformation grant was awarded to UMass with the intention to engender a healthy environment that will bridge gaps of gender and racial diversity present in UMass STEM colleges, as well as empower underrepresented faculty. According to the campus climate survey of 2016, black, Latinx and biracial faculty represented only 10 percent of faculty in the College of Natural Sciences (CNS).

Despite the progressive conversations around creating greater racial diversity in STEM, there was a tangible absence in the room. Where were the students the program was intended to impact?

Sebastian Vega, a sophomore studying political science and biology, noticed the diversity difference immediately when he stepped on campus. Vega is native of Miami where “white was the minority” and UMass was “kind of a culture shock.”

Anusha Kulkarni sitting in the Integrated Learning Center. (Julia Donohue/Amherst Wire)

Like Vega, Anusha Kulkarni, a computer science sophomore, felt intimidated by the difference in her setting. Not a racial difference, but a gender difference.

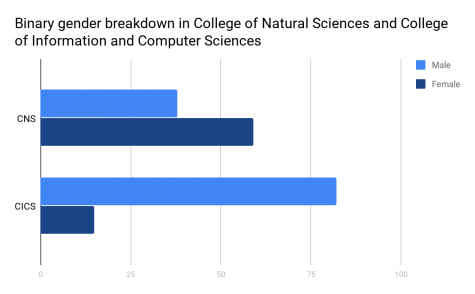

Hailing from Advanced Math and Science Academy, ranked second out of all the high schools in Massachusetts, Kulkarni developed her scientific interest in classrooms she felt were evenly divided. Yet at UMass, where the College of Information and Computer Sciences reports an 82 percent male population, Kulkarni retreated in classes.

“I don’t want to make myself stick out,” Kulkarni said. She rarely speaks up for fear of asking a “stupid question.”

“I feel like people try to think science has nothing to do with society or doesn’t intertwine with things like sexism or racism but it does,” said Juliana Babu, a sophomore biochemistry and neuroscience major who echoed Kulkarni’s discomfort.

Babu claims the consequence of male domination in STEM fields directly correlates to a negative impact on marginalized groups.

“Eugenics and things like that are literally based in racism,” she said.

“Science for a long time was very racist and sexist… it’s a field that really needs people of color in it,” Babu said as she still struggles to confront an issue that impacts her education, career and future.

How should the university confront this issue?

“Encourage more diversity in STEM,” Kulkarni suggested.

“Admit more people of color,” Babu said.

“Creating more programs or classes where you do have a more diverse field,” said Vega, who explained how these programs would benefit both the marginalized and the majority. “When you’re exposed to a more diverse group of people you’re less inclined to generate hate crimes on the basis of people you’re not familiar with.”

Joya Misra sits in her office. (Julia Donohue/ Amherst Wire)

Joya Misra, professor of sociology and public policy at UMass, analyzes the data for the campus climate survey and studies the impact of gender disparity in STEM.

“Girls and boys are equally capable in STEM fields,” Misra said, based on her decades of research. Misra continued on to discuss that while girls are performing better, they are often feeling less confident than their male counterparts resulting in a drop off in scientific career interests.

For the women who end up in STEM majors and careers, this disparity depends on which particular fields they pursue. While Kulkarni represents one of the 15 percent of women in computer science at UMass, women surpass the median with 59 percent representing all undergraduate students in CNS.

“Women have been raised to be selfless,” Misra said. For this reason, Misra concludes that biology has more women than physics because biology has clear pathways to a selfless impact on the world, for example, becoming a doctor.

As for how the university could work to be aware of these disparities, Misra asks faculty to challenge their assumptions. Faculty must “disentangle ability and background” when teaching students from lower achieving school districts.

However, a 2015 research study from the Brookings Institute revealed that black and Latinx students attending lower achieving schools is not an assumption, but a statistic.

Tracie Gibson is actively working to bridge this sizable gap. Gibson was named as the first director of student success and diversity for CNS. In only a year and a half at UMass, Gibson sees a major difference in retention between all students in the college. From the entering class of 2014, 75.1 percent of all students graduate while only 57.8 percent of underrepresented minorities go on to receive a degree.

“We try to create bridge programs,” Gibson said. These “bridge programs” include online preparatory courses and a residential program the week before the semester begins. The courses include Bio Prep and Chem Prep, the latter established ten years ago.

A board dedicated to brainstorming in Gibson’s office (Julia Donohue/ Amherst Wire)

Out of 1,400 students enrolled in introductory biology courses, which is the only requirement to access Bio Prep, 1,200 accessed the course. 85 percent of students enrolled in introductory chemistry courses accessed the sister service. Gibson then lists several community building endeavors she has established in the past year and a half: book clubs, ice cream socials and a speaker series to name a few. Highly personable, Gibson beams when discussing her work.

“Can we do better?” Gibson asked herself as she reflected upon the community building she’s tried to manifest within the past year and a half.

“The answer is yes,” Gibson said.

Elizabeth Connor, the associate dean for undergraduate education and development in CNS, works closely with Gibson to engage underrepresented minorities and first-generation students. On April 16, Connor and Gibson received approval for a grant that will be used to post pictures of underrepresented minorities around campus.

“You need to see yourself in the people teaching you,” Connor said. She is attempting to engage and grow a community within CNS, but it’s been difficult. “We’re going to say we’re a community and then work on it. Hard,” Connor emphasized.

Connor begs faculty to view students with expectations. She wishes faculty would see a new student and think, “Here she is; she can do anything.”

Reflecting on her work and the work ahead of her and her team, Connor appears exhausted but hopeful. Her eyes widen and Connor rolls off a laundry list of her robust agenda. Non-stop, she passionately pushes small questions into overwhelming answers about the intricacies within incorporating marginalized communities. There is no air left in the room to breathe.

Finally, she paused.

“All we can do is try,” Connor exhaled.

When reached for comment from UMass Amherst administration, Associate Chancellor for Equity and Inclusion Anna Branch had no statement.