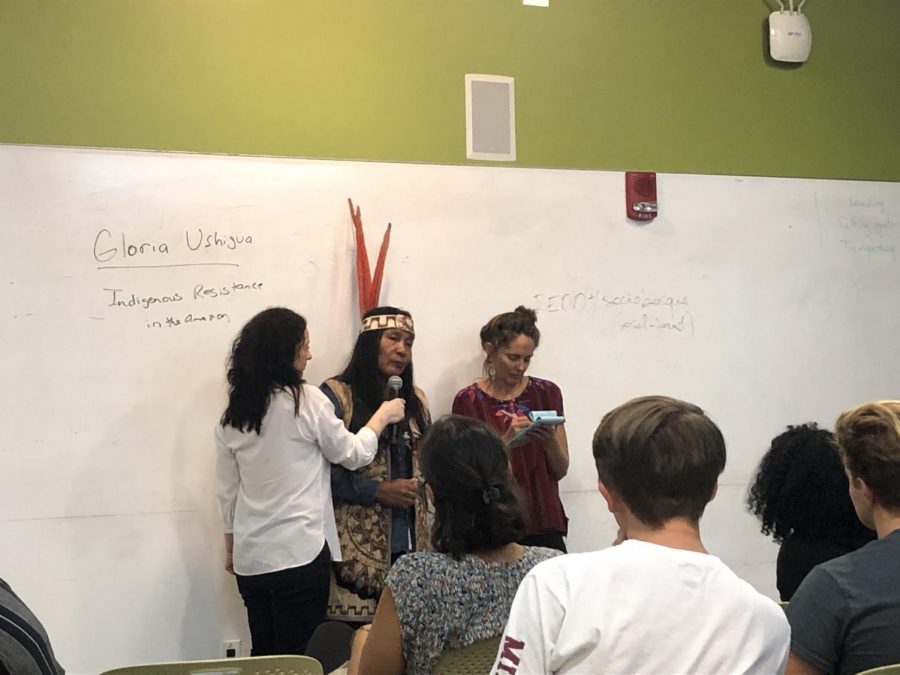

Environmental rights defender Gloria Ushigua discusses her activism at UMass

“The territory is mine; the territory is of the spirits living under the earth and under the water.”

*Editor’s note: Ms. Ushigua gave this speech in Spanish, her second language. Manuela Picq, a professor at Amherst College acted as moderator. The reporter, Harry Ortof, is not proficient in Spanish. Anytime Ms. Ushigua is quoted, it is in full attributed as “…as paraphrased by Manuela Picq.”

Leader of the Sápara women’s organization Ashiñwaka Gloria Ushigua spoke about her activism in the Ecuadorian Amazon Wednesday, Sept. 25, five days after the UMass Amherst Sunrise Movement’s “Walk Out for Climate” rally. The event also included a brief Q&A with audience members.

Ushigua primarily defends her ancestral land from state-owned and private companies trying to harvest oil in Sápara territory. As a result of her work, she has been increasingly harassed by public officials and law enforcement—on August 19, 2015, three policemen broke into Ushigua’s house, shocked her with tasers and beat her. The next year on May 2, 2016, Ushigua’s sister-in-law Anacleta Dahua Cují was murdered.

In 1998, Ushigua moved to have Sápara recognized as a nation. She began with organizing with the women in her community since the men wouldn’t allow her to be president of the entire Sápara nation.

“We had an assembly of women and they positioned me as the president of the nation. The men were very upset. They complained a lot, but at [the] end of the day, all the other women held me up and we convinced them, just by their regular complaints, in letting me lead the politics for the entire territory,” Ushigua said.

After a countrywide protest organized by two indigenous organizations failed to achieve their goals, Ushigua moved to New York. With the help of an organization called Vida Y Tierra, Ushigua traveled the world and met other indigenous people.

“There are indigenous peoples everywhere, and I understood that they had lost their land, too. They told me that they, the outsiders, would come in, develop programs, [make] promises, encourage us to sign treaties [and] conventions for them,” Ushigua said. “The governments came in with treaties and licenses and they didn’t do the treaties with us. They actually did the treaties with international companies.”

In 2013, a Chinese oil company tried to extract the oil from Ushigua’s land, prompting her and other Native women to present a document to the Ministry of Energy in Quito — however, the Ministry refused to accept their documents. Ushigua and other Native women wrote letters to the Chinese government, criticizing them for not consulting them before moving forward with the oil extraction in their territories. After a while, the Chinese government told the Ecuadorian government they would not extract any more oil in their territories.

When asked why climate change urgently needs to be addressed, Ushigua said:

“Because where I live, we don’t go to the supermarket…I just put out my hand and pick up my food…We fish, I hunt, but there’s no more food. There’s no more food, the rivers are overflowing, the…are coming and [chopping down] all the trees. It’s happening everywhere. Life is dying – and all of that for money… you are young, you can keep up the struggle with this, you can take the message to people to stop all this business that’s killing life.”

One audience member asked Ushigua, “What is the way we, as Americans, can help pressure leaders of countries that have the Amazon rainforest or other countries?”

“Send letters — lots of signatures. If you send a letter with 20,000 signatures, it will make an impact. In [Ushigua’s] case with China, it shows presence, concern, that the world is watching, and you aren’t indifferent to what’s happening… be present through letters and signatures.”

You can donate and sign a letter of support for Ushigua’s people here.

E-mail Harry at [email protected], or follow him on Twitter @HarryOrtof.

Email Harry at [email protected], or follow him on Twitter @HarryOrtof