“Minari” tells a familiar, but unique story of the American dream

The American dream isn’t a story of rags to riches, it’s a story of difficult choices and constant survival.

“Remember what we said when we got married? That we’d move to America and save each other? Instead of saving each other, all we did was fight.”

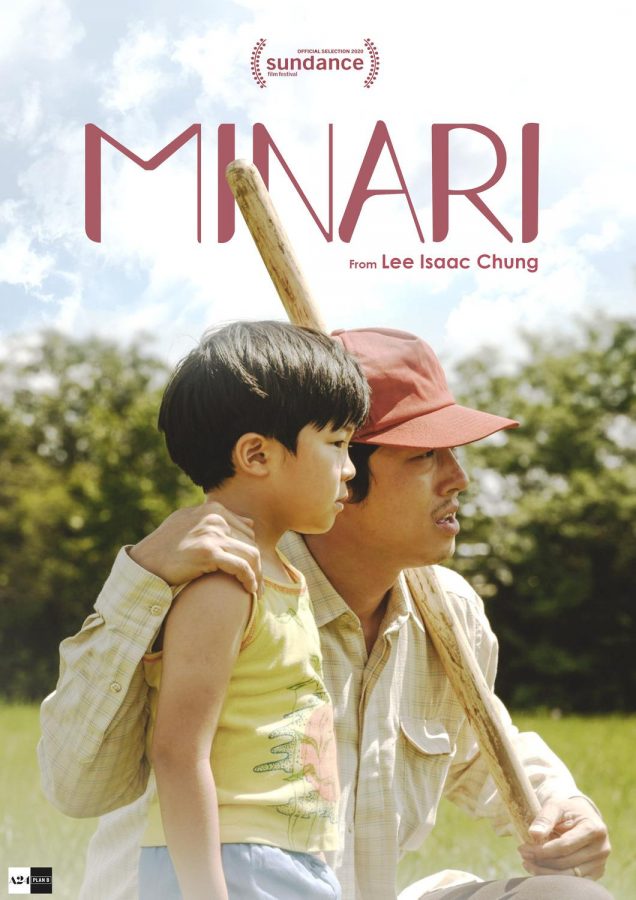

Immigrant family stories have been recreated several times, especially in recent years. “Minari” is another semi-autobiographical immigrant family story, but reformulated by director Lee Isaac Chung to the point where it stands out from the rest.

Jacob Yi, played by Steven Yeun who is most known for his role as Glenn in “The Walking Dead,” leads his immigrant Korean family in moving from a Californian City to a mobile home in empty rural Arkansas so that he can start his career in farming.

To support his family, Jacob and his wife Monica, played by Yeri Han, work as chicken sexers alongside other Korean immigrants. Money does not come easy in this empty setting and is one of many obstacles that the Yi family must overcome in this movie. What sets “Minari” apart from other American Dream movies is that it doesn’t just tackle the struggle of attempting success in America, it pushes through the coinciding struggles of acclimation to a new culture and raising a family in such difficult conditions.

The American dream is different for everyone, but to Jacob, it means one thing: freedom. Becoming a successful farmer in rural Arkansas would mean Jacob is free from his monotonous factory work and can provide money for his family in a more independent way. Jacob’s riches story is a dream that seems unattainable both to the audience and, more so, to his wife. A great draw to this story is witnessing Jacob change as he gets closer or deviates from achieving that dream.

When Chung conceptualized this film, he wanted a film that touched upon his experiences growing up around the Ozark mountains. He emphasized “that farming is really, really difficult work” to people that are unaware of the difficulties of maintaining a stable life during this time.

“Minari” begins with Jacob about to purchase water well installment on his land. When Jacob refuses to spend $300 dollars on the water well installment and opts to work on it himself. I caught myself audibly frustrated by his thinking. The audience could tell from a mile away that this decision would return to haunt Jacob. Later, he gladly purchases a $2,000 tractor from a crazed pious man named Paul who he hires as a farmer, much to his wife’s dismay. Paul then recommends that Jacob grow American vegetables for more profit. Despite the well-suited advice, Jacob wants to stick with what he’s familiar with in order to sell to the 30,000 Korean immigrants that move to America each year.

When Jacob grows the Korean vegetables, Paul believes that Jacob is not growing them correctly, but his stubbornness kicks in and neglects Paul’s much-needed advice. I give Chung props for repeatedly spotlighting the struggle to be a successful person and the initially irrational choices that need to be made even if people disagree with those choices. Moreover, it’s interesting to see how Monica reacts negatively to an initially irrational decision only to see that it pays off in the end.

As immigrants, Jacob and his family only experience a few minor incidents where they succumb to racial exclusion. In their work, Jacob and Monica are greeted with familiarity as they work alongside other Korean migrants. However, Monica feels as though exposure to other Korean people only through work is not enough. To make up for the lack of familiar community in Arkansas, Monica and Jacob decide to bridge this gap by attending a local, non-Korean church, something that at least bears some familiarity with the Yi’s.

In one scene, the priest starts his sermon by welcoming any new church-goers to stand up. The Yi’s, the only non-white group, are the sole family to do so. That sense of being put on the spot as well as that sense of exclusion amongst a large group of people is something that I resonate with a lot personally. After mass, the children, David and Anne, are questioned by other children about their Korean culture and heritage. Some of the questions that they pose may seem offensive, but it is juxtaposed by the fact that they are children who probably don’t know any better especially with the lack of diversity in their community.

What I feel like “Minari” lacks is a complete and more obvious showcase of the culture acclimation and tension in 1980s Arkansas as a Korean family. The film touches upon these issues explicitly in a few instances and when that does happen, the only times that the film does so are the scenarios listed prior. For such a big movie and given current events, I do wish that director Chung tackled these issues more forward. However, because this movie is semi-autobiographical and every interview that I’ve come across doesn’t really mention an extremely difficult cultural clash growing up, maybe Chung just didn’t find this problem nearly as apparent as his family’s economic struggle. Therefore, it is still admirable that Chung touched upon this subject. Although these issues aren’t mentioned explicitly in a lot of detail, going through this movie after an initial watching made me realize how the director addresses this through different and very clever means that I mention later.

I appreciate how Chung illustrates Monica bridging her social gap by looking for some sort of familiarity, religion. That would be something that I along with others would do personally. Don’t doubt it, when you came to UMass, one of the first things you did was find social outlets and extracurriculars that suit your own personal interests. Because of this, I was attached to Monica for her relatability.

In real life, parents often want what is best for their children. However, they will constantly combat amongst themselves for what they believe “best” actually means. Chung’s approach to this conflict is as real as it gets as he sets both Jacob and Monica against each other when what they both want in the end is a sense of unity in the family.

Monica is never happy with her family’s living situation in Arkansas. She sees the open fields of Arkansas as desolate, saying that it’s too far away from a hospital in case of an emergency, the Korean community isn’t big enough and their actual mobile home isn’t suited to her standards. Conversely, Jacob doesn’t look at what is in front of him at the moment. Instead, he looks at the big picture. If he were to successfully start his farming business, he would be able to quit chicken sexing within three years and leave more than enough money for his two children. Monica immediately wants to leave and wishes to go back to their Californian city where they moved, saying that an urban Californian community would be a better place to raise David and Anne, even if it means working tediously as chicken sexers.

However, Jacob risks everything and demands that the family stays in Arkansas to grow wealthy within a few years. These two contrasting views on raising children are apparent all throughout “Minari’s” two-hour runtime and because of this, I found myself bouncing back and forth between Monica’s reasoning and Jacob’s reasoning. The rural Arkansas landscape, while gorgeous to look at, bears a small community and a smaller Korean community. As a child, I would have hated having to live there. The situation gets so drastic Jacob cuts off the family’s water supply to save his farm. I felt less sympathy towards him as I saw his family having to fetch water from a nearby creek instead of using a faucet, but at the same time, I realize that he is doing what he is doing for the betterment of his family in the long run. At this point in the movie, he’s been cultivating his farm for quite some time, so why should he stop now? But at the same time, I questioned if Jacob was doing what he was doing for his family or for himself.

“[The Children] need to see me succeed at something for once,” Jacob said.

This back-and-forth between sides not only captured me but made me critically think about what I would do personally.

The ensemble is small, but each character stands on their own and is integral to the story-telling that it’s hard to forget about anyone.

Paul, the pious crazed man that helps Jacob farm, is so outrageously boisterous, but he lacks personal depth at first glance. One of Jacob’s first interactions with anyone is when Paul sells him the $2,000 tractor. Frantically, Paul offers to work for Jacob given that he was stationed in Korea during the war and is familiar with Korean vegetables. Because of how psychotic Paul appears, Jacob and the Arkansas locals alike feel intimidated by his presence; some of the children taunt him on the bus ride from the church. Despite external and societal judgment, Paul is good. He helps boost Jacob’s career and becomes his closest friend because of their working relationship, Paul finds himself invited to share dinner and pray with Jacob. Paul is illustrated as an unusual bridge between American and Korean culture for Jacob. I found it fascinating how Chung illustrated Paul’s character.

“Sometimes even [my immigrant parents] would say things about the local community, like, ‘What are these crazy people doing?'” Chung said in an interview with The Austin Chronicle. “Paul is based on a real person who lived in Lincoln, Arkansas… Our experience with him was that the more we got to know him, the more human he was to us, and that’s how I wanted the film to unfold – that all these relationships might start off with something strange and funny and spectacular, but they really give way to a deeper understanding of who these people are.”

At first glance, Paul is an old man who freakishly speaks in tongues under his breath and literally carries a cross on his back across town as his way of showing worship. It’s a little bit disappointing that Paul wasn’t used as a bridge for the entire Yi family, especially Grandma Soonja who was the least familiar with American culture. This goes in tandem with my previous critique that the movie does not delve into acclimation of cultures enough. Initially, I thought of Paul as a cheap unnecessary side character who acts as comic relief. I fell victim to what Chung was trying to speak against. Paul has more complexity to him than just some crazy old man. He’s the prime example of getting to know someone before judging them. It felt as though his character was a distraction, but what I was missing was the big picture: don’t judge a book by their habit of dragging a crucifix on their back across town. This literary lesson might go over some heads, but looking back, Paul’s character is as important as any of the Yi family. Chung does go into depth with the acclimation of different cultures, but in a way that is not obvious and black-and-white.

The other biggest supporting character, Grandma Soonja, is a gem and is objectively a much-needed aspect of the script. She is introduced after Monica pleads with Jacob that someone needs to watch David and Anne while they are at work. They fly Grandma Soonja from South Korea to Arkansas. Grandma Soonja on her own is great. She’s what everyone expects out of a grandma. She gives a lot of gifts to David, plays cards and wants to have a close bond with her grandchildren. I felt a warm and fuzzy feeling inside seeing the parallels between Grandma Soonja and my own mother. However, in David’s eyes, she is the exact opposite of what a grandma should be. David’s perception of a grandma is very Americanized, considering that he was born in America. He believes that grandmas should love to bake cookies, should never use swear words and should not “smell like Korea.”

David’s conflict with his grandma is much like Jacob’s conflict with Monica in the sense that both oppose each other despite wanting the same thing in the end. David dislikes his grandma because of how different she is compared to his own more Americanized expectations. Grandma Soonja dislikes David because of how out-of-touch he is with Korean culture. In interviews, Chung mentions that he put himself in each member of the Yi family’s shoes, but his earliest perspective was from David’s point-of-view. The interactions that David has with his grandma felt very real and personable because of this. They both want to get along with each other and have a true “grandparent-grandchild” relationship, but what strays the two away from this is their own preconceived notions of how the other person should act. Although the relationship begins fragmented, seeing the two learn to get along with each other was equal parts heartwarming and comical. In one scene, David wants to prank his grandma by doing something that I don’t want to say because it is both explicit and would ruin the movie. Grandma Soonja’s reaction is hilarious, but seeing the entire family discuss the situation felt sincere. Chung was able to instantaneously switch moods all throughout the movie and not once did it ever feel forced. The sense of familiarity within the Yi family made every aspect of their relationships feel natural and never out-of-place. Although this conflict is more brushed over compared to Jacob v. Monica, I found it to be an interesting commentary on keeping in touch with your cultural roots and understanding each person’s situation before passing on judgment and hatred.

“Minari” does not paint the American dream as a story of sudden riches, but rather a story of constant survival and difficult choices alongside other people affected. Throughout its runtime, the movie goes is a rollercoaster of high hopes and complete despair, parallel to the process of being successful in America. In the last scene, the Yi family is at their lowest point ever and if I were in their shoes, I would give up. However, being so far down does not stop them, they see it as an opportunity to not look back and rise even higher than ever before. Being successful is not some instantaneous occurrence that happens at the snap of the fingers, it’s a process that tests one’s willingness to move on despite trampling on hurdles along the way. I would recommend at least one watch. It’s not just a movie, it’s a lesson about the harsh truth and survival when migrating to America. As I watched the credits sequence, it felt as if my heart was broken, but then stitched together again.

“Minari” is now showing in select theaters and currently available to rent through various streaming services. Consult CDC Safety Standards before viewing in theaters.

Email Aaron at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter @WhatTheFacundo.