Hazy smoke lingered over sweet sounds of local music and easygoing conversation as weed enthusiasts gathered for an annual celebration of the plant.

When 1,400 people attended the 31st Extravaganja festival on April 19, 2025, patrons were free to discuss openly —and smoke— a shared love: marijuana.

The free event hosted by the Cannabis Education Coalition (CEC), a University of Massachusetts registered student organization, reflects Massachusetts’ progressive strides since becoming the first New England state to legalize cannabis in December 2016. However, the CEC’s efforts have extended far beyond the states’ legalization. Founded in 1991, the UMass CEC serves as the oldest active student-run organization in the U.S. focused on reversing the prohibition on marijuana.

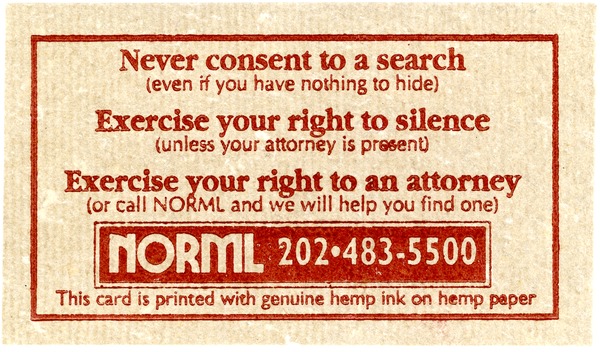

Local food vendors lined the Franklin County Fairground, dishing out everything from pulled pork sandwiches and empanadas to boba tea and ice cream, ready to satisfy every “munchies” craving a festival goer could have. Extravaganja attendees also had the opportunity to buy marijuana seeds, look at glass smoking pipes, and talk to local dispensaries like Mass Alternative Care. Extravaganja’s purpose extends beyond a general celebration of the plant, however, as the festival seeks to promote marijuana education. The Massachusetts Cannabis Reform Coalition (MassCann), a grassroots marijuana legislation non-profit, hosted an education village near the event’s entrance. As a longstanding marijuana reform group, MassCann set up four discussion panels at the event to discuss topics such as consumer rights, cannabis safety, the effects of cannabis on the body, current public policy surrounding the drug, and how to grow the plant legally. CEC president Blake Weiss, a UMass horticultural science major, emphasized the festival’s importance as a form of learning more about cannabis.

“Thanks to legalization and creation of the [cannabis] industry, we can have people come talk about consumer safety,” said Weiss.“[Extravaganja] gives people an opportunity to learn something new and connect with the people around them.”

The positive attitude regarding marijuana held by Extravaganja attendees reflects a shared belief by the U.S. people. According to a 2024 study by the Pew Research Center, “88% of U.S. adults say marijuana should be legal for medical or recreational use.” However, public opinion surrounding the plant was not always this favorable, to say the least. Stemming from efforts such as Reefer Madness (1937), a hyper-exaggerated movie warning teenagers about drugs, and harsh government stigma surrounding marijuana use, public support for the plant hovered at just 12%, according to a 1969 Gallup poll. Only a year later, one man sought to change this narrative.

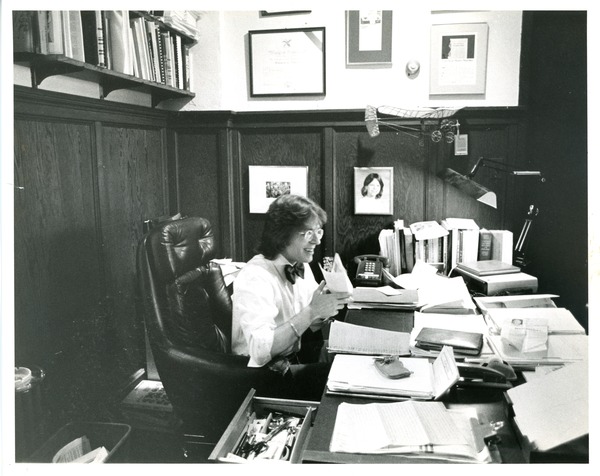

In 1970, Keith Stroup, a Georgetown graduate and public interest lawyer, founded the first mainstream cannabis reform group, the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), despite his stance being on the fringes of society. With over 60 years of continued grassroots activism and legislative influence, NORML developed into the largest marijuana advocacy nonprofit in the U.S. Without NORML and its efforts, much of the marijuana policy progress seen today would not be possible. Their unprecedented work is immortalized at UMass Amherst’s Du Bois Library, where 84 archival boxes filled with documents, images, and video recount their historical impact on the marijuana plant.

“A lot of my contemporaries thought I was throwing away my law degree,” said Stroup. “Well intentioned friends were saying, are you sure you want to do this? And I said, well, I want to legalize marijuana.”

The criminalization of pot was, and still is, controlled by political agendas. The Controlled Substances Act, passed in 1970, categorized cannabis as a Schedule I drug alongside heroin, MDMA, and hallucinogens like LSD. Nixon, described by Stroup as “an infamous marijuana zealot,” created the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse in order to confirm marijuana’s Schedule I categorization. The 13-person committee, nine of whom were individually selected by Nixon, had no actual familiarity with marijuana.

Tom Ungerleider, a member of the commission and a former professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, invited around a dozen marijuana smokers to a private event in order to learn more about the drug.

“What [the commission] saw,” said Stroup, “was everybody relaxing and having a good time, nobody was doing anything violent or radical. They recognized there was no basis to treat it as a crime.”

In 1972, the group published their findings in the Marijuana Signal of Misunderstanding and recommended that the U.S. government eliminate penalties for the possession and use of small amounts of marijuana. Nixon, with the support of Congress, rejected the findings of his commission.

Cannabis remains federally illegal in the United States. However, on May 2nd, 2024, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) officially commented on an initiative to change marijuana to a Schedule III drug, potentially altering a 50-year precedent. The first hearing, set to occur on January 21, 2025, was postponed due to an interlocutory appeal, according to the DEA.

NORML spearheaded legislative marijuana efforts throughout the 1970s, with 11 states decriminalizing the drug by 1978. After only six months in office, President Carter also commented on support for decriminalization.

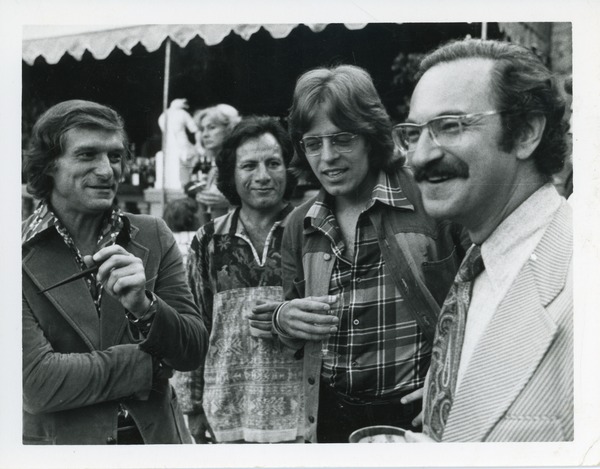

A large reason behind NORML’s early success stems from its relationship with the Playboy Foundation. Former Attorney General Ramsey Clark, who supported legalizing marijuana in his novel Crime in America, and whose father, Thomas Clark, had served on the Supreme Court, connected Stroup to Hugh Hefner and supported his legalization efforts. Margaret Standish, Playboy’s former executive director, helped push a standard commitment of around $100,000 per year from the company. Playboy also assisted NORML by regularly giving them full-page ads in their magazine.

“Anytime we managed to get some young college kid out of prison who had been locked up on a marijuana possession,” Stroup said, “Playboy covered it at the front of the magazine.”

Playboy had around six million subscribers at the time, with readers often sharing the magazine with their friends.

“[NORML] had a mailing list of 2,000 people at the time,” said Stroup, “so it was incredibly important during the early years.”

Despite early legislative progress, after 1978, NORML went 18 years without a single statewide victory on marijuana-related cases. This was primarily due to both Nixon’s War on Drugs campaign and Ronald Reagan’s “Just Say No” initiative, essentially reversing all of NORML’s public opinion progress. Additional hardships occurred after the DEA failed to prohibit the use of paraquat, a harmful pesticide, on marijuana plants in Mexico. Stroup, out of frustration, infamously outed Peter Bourne, the former director of the White House’s Drug Abuse Policy Office, for doing cocaine at a NORML party in 1977. This created a chilling effect in implementing progressive cannabis policy and reversed any positive relations NORML had with the White House.

However, the group continued to advocate for marijuana reform in defiance of years of legislative defeats, achieving success again in 1996 with California’s Compassionate Use Act. This bill legalized medical marijuana within the state. Today, 38 states allow the use of medical marijuana, in addition to 24 states legalizing recreational use.

“When you look at the progress we’ve made, it’s important to realize it wasn’t because we had any particular tricks to win. It’s because over a long period of time, we’ve won the hearts and minds of the American public,” said Stroup.

After decades of work from companies like NORML, when reform efforts were heavily opposed, American politicians are finally following public opinion. Archival records from UMass Amherst’s NORML Collection show that in the past, five college students, despite being members, showed hesitancy when publicizing their support for legalization. In a 1987 NORML member involvement survey, a former Hampshire College student, Thomas Schnieder, said his friends were “supportive but hesitant” to join the legalization efforts.

“People realize the cause is true but remain fearful of the powers that be,” said Schneider in the survey.

NORML and its staff have always known about the internal struggle to create public progress for marijuana.

“The history of cannabis policy reform is defined by incrementalism and taking two steps forward and one step back,” said Morgan Fox, NORML’s current political director. “It’s not viewed as a priority issue, at least by lawmakers.”

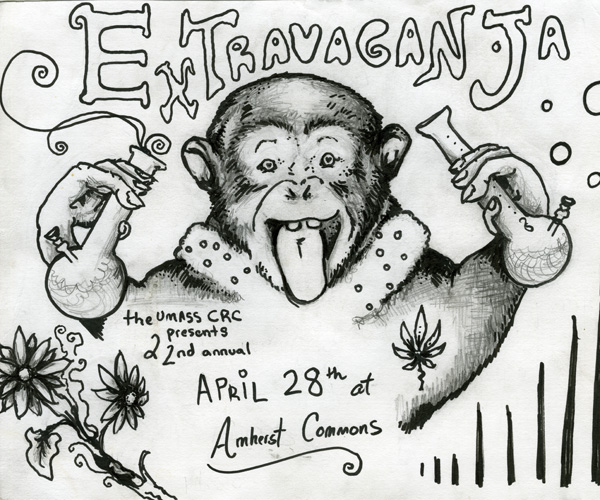

In addition to NORML, the UMass Cannabis Education Coalition is not unfamiliar to the idea of gradual progress regarding weed reform efforts. The student-run group began advocating for cannabis law reform 25 years before Massachusetts legalized marijuana statewide. Extravaganja represents a collective effort of continued advocacy built from the foundations of previous members. The UMass CEC’s 2013 Extravaja festival is seen below, representing the 22nd time the event was hosted.

Cannabis reform policy, as mentioned by Fox and Stroup, represents a decades-long, incremental effort that endured many setbacks and hardships. It is through the endeavours of groups like the UMass CEC and NORML that, despite major roadblocks, persistent advocacy forced change. While the organizations uniquely represent national and local cannabis agendas, their goal remains the same: to destigmatize negative attitudes about marijuana held by the American public and government officials through increased education and awareness.