Why does UMass love Coke? Students question pouring rights at flagship campus

A $6 million deal has made UMass Amherst Coca Cola country.

This article has been updated to include UMass’ response to a letter sent by the Student Government Association about their pouring rights contract with Coca Cola.

AMHERST – Inside three of the University of Massachusetts’ four dining halls, you can find at least one Coca Cola soda fountain hunkered down at a beverage station. Crates full of glass cups sit a few feet away as a wide array of sugary drinks are at your disposal.

The same goes for Blue Wall Cafe and at Chicken and Co. @ Southwest, where students have access to Coca-Cola Freestyle, a touch screen soda machine that can serve over 150 coke products. Even if you don’t drink soda, your ice still comes from these branded machines.

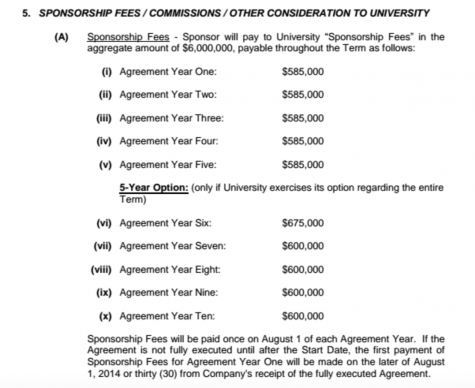

You could say UMass has a coke addiction, but the university doesn’t heavily push the all-American beverage onto students out of fandom. It’s thanks to pouring rights contracts, a common practice among universities where beverage companies pay large sums of money – $6 million in UMass’ case – to have their product exclusively distributed on campus.

“University will use its reasonable, good faith efforts to maximize the sale and distribution of Company Beverages on Campus,” according to UMass’ agreement with Coke. “At a minimum Company Beverages shall be widely available for purchase by consumers on the Campus, and will be sold and/or served as part of all meal plans provided to University students and/or others on the campus.”

With the first half of the contract ending July 31 and the second part up for renewal August 1, students have created a petition urging the university to opt-out of the deal. It’s a move that would have UMass miss out on over $3 million over the next 5 years.

UMass’ social responsibility should outweigh this lost income though, according to Jon Blum, who helped create the petition with his group Uprooted and Rising at UMass Amherst. As part of a national movement, Uprooted aims to end the involvement of big food and beverage organizations have in higher education.

“We are trying to create a productive dialogue to explain to students on why pouring rights contracts restrict their freedom to purchase the beverage products that they want,” said Blum, a sophomore economics major at UMass. “We also believe that neither pouring rights nor Coca Cola represents the values of this campus.”

Their efforts likely won’t get immediate results due to a clause in the contract stating, “University shall notify the Company of its intentions to renew no fewer than 180 days prior to July 31, 2019.” However, UMass’ Student Government Association is using these next five years to build a foundation for a campaign against the contract.

In April, members of SGA approved to endorse a letter asking UMass to rethink their relationship with Coke and create a task force to research the transition to a local beverage provider.

UPDATE: In a recent response to SGA, UMass Chancellor Kumble Subbaswamy agreed to create a working group next semester to review the contract. The letter also revealed that under Massachusetts law, UMass cannot deny any company from bidding for the contract.

“Therefore we are unable to endorse or commit to not renewing the current vendor Coca Cola when the contract is next up for renewal,” Subbaswamy wrote in the letter.

Key points from the contract reveal that, aside from a handful of distinct exceptions, Coke products are the only beverages allowed to be distributed and sold on campus. Instead of Lipton, Muscle Milk or Rockstar Energy Drink, students only have access to Honest Tea, Core Power and Monster Energy. Some exceptions include freshly made smoothies and juices, unbranded fresh milk and Ocean Spray juices. But, odds are, if you see a drink on campus, it’s a Coke product.

UMass is also allowed to stock up to 20% of its shelves with locally made beverages. The one stipulation being that a similar Coke product must also be made available.

Blum cites this restriction on local products as one of the most pressing issues of the contract. It strictly limits UMass’ ability to supply more locally-based and humanely produced beverages, also known as ‘real food.’

UMass has committed to the purchasing of ‘real food’ through the Real Food Campus Commitment, an agreement that challenges schools to have 20% of their purchases be real food. Chancellor Subbaswamy signed the agreement in 2013 with the goal of hitting the mark in 2020. Its progress is unknown, but UMass claims it’s “on track” for the goal.

“UMass Dining proclaims: ‘Our sustainable practices not only benefit our campus but our global community as a whole,’” wrote Blum in an op-ed covering pouring rights at UMass. Over the years, UMass Dining has pushed sourcing more food from local farms and has invested $4.5 million in local farming initiatives, but students like Blum believe more can be done. “By ending the contract, UMass Amherst can live up to this vision.”

Coke’s shoddy ethics is also a concern for unsatisfied students. The petition cites multiple reasons why Coke fails to align with UMass’ sustainability efforts. One example includes the company’s excessive use of water supplies in India. It also outlines the company’s violations of labor rights, another disqualifier to be considered ‘real food.’

Despite their bad track record, universities are using the money from these deals to help offset costs that are a result of cuts in state funding. From 2001 to 2017, Massachusetts slashed funding for higher education by 14 percent, totaling over $200 million. According to a campus-wide email from Chancellor Subbaswamy, UMass could also face an $8.2 million deficit for the 2019-2020 school year due to proposed tuition freezes from the Massachusetts Senate.

But with the exception of $60,000 allocated towards merchandising each year, UMass’ use of the funds is a mystery. The UMass News and Media Relations office has yet to respond to the Wire’s inquiry about the contract and the allocation of the funds.

Before the initial records request for the contract, Coke’s ties to the campus were also unknown.

“…University agrees that the amount of Sponsorship Fees to be paid to University by Sponsor under this Agreement, and the other terms and conditions hereunder, will be kept confidential by University…,” states the contract. This is a common stipulation among other pouring rights contracts. Parts are often redacted or universities refuse to release the agreement altogether, according to a 2018 Muckrock investigation.

Even without a contract to comb through, students at John Hopkins University in Baltimore, Md. have spent the past semester advocating against their contract with PepsiCo, Coke’s main competitor for pouring rights contracts. Through Pour Out Pepsi, students like Katie Smith have made it their mission to educate students about the deal and the beverage they are, essentially, forced to consume.

“There are so many aspects people don’t realize,” Smith said. As an intern with her school’s dining department, she’s scheduled multiple meetings with administration to discuss the contract. Similar to UMass, 80% of beverages sold on-campus must be Pepsi products. John Hopkins will also receive $2 million over the span of its contract, according to Smith. Additionally, Pepsi’s violation of worker’s rights goes against John Hopkins’ ‘real food’ initiative. With no access to the actual agreement, Smith’s group can’t know for sure if the university is being completely transparent or honest.

Universally, students are unaware of these contracts. Pour Out has taken strides to educate their peers, but progress has been slow and time is a factor. Like UMass, their contract is up for renewal later in the year.

“The issue is, the people who know about the Pepsi contract at all is pretty small,” said Smith, noting the group’s online petition has only received around 200 signatures. That’s around 3.5% of the school’s 5,600 undergraduate class. “Whenever we talk to students, they are like ‘yeah that is kind of sketchy’…but its hard to get through to more students.”

Ending these contracts isn’t out of reach for proactive schools. In 2015, San Francisco State University students successfully advocated against the school’s request for a pouring rights contract.

Only time will tell if these results are possible for UMass or John Hopkins, but Blum is willing to take any victories his group can get. Whether that be informing more students about pouring rights or inspiring positive changes to future contracts.

“The campaign is deeply looking forward to engaging with this issue and fighting for a future where UMass no longer has a contractual relationship with problematic companies such as Coca Cola,” Blum said.

Email Brian at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter @brianshowket

"The hero of my tale–whom I love with all the power of my soul, whom I have tried to portray in all its beauty, who has been, is, and always will be...