Manilla folders containing guerrilla warfare strategy pamphlets, firearms guides, and self-defense manuals occupy five unassuming boxes in UMass Amherst’s W.E.B. Du Bois Library.

Chronicling the waning days of a leftist militant group that would come to leave an indelible mark on the American mind, the Weather Underground Organization (WUO) collection also includes internal correspondence and communiques by its members. With the majority of the collection’s material dating to the mid-to-late 1970s, it offers a unique look at the WUO during a period when their revolutionary ambitions came to sag under the weight of FBI manhunts, post-Vietnam malaise, and widening internal schisms over ideology and strategy.

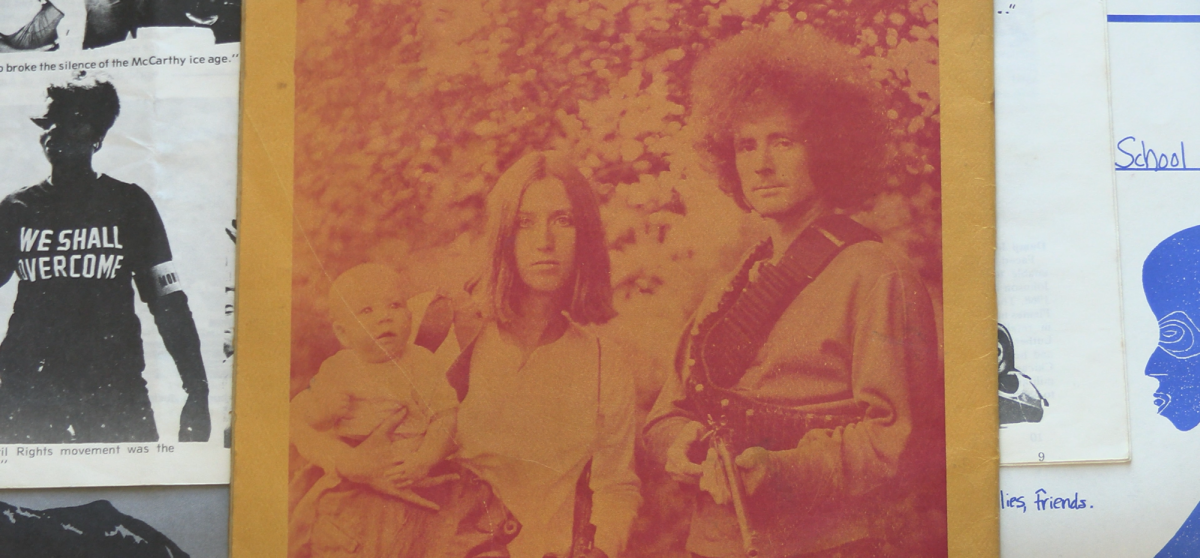

One self-defense manual in the collection has a photo on its back cover portraying a hippie couple. The woman holds an infant in one hand and a revolver in the other. The man points a rifle in the direction of the camera.

Published in the late ‘60s, the image reflects a marriage of militant action and the Vietnam-era counterculture that contrasts with Woodstock and The Summer of Love, which seem to define how we remember this period today.

Yet, according to scholars who have extensively studied the WUO and the rapidly changing social landscape of 1960s and 1970s America from which they emerged, this coupling was more common than one may think.

Jeremy Varon, a professor of history at the New School for Social Research in New York and self-described “Weather Whisperer,” wrote “Bringing the War Home,” a detailed history of the WUO and similar groups that operated at the time like the Red Army Faction of West Germany.

He characterized the late 1960s and the transition into the ’70s as an “apocalyptic” time for those who found themselves questioning the cultural and political status quo, citing the Kent State shootings and murders of Black Power leaders.

It was out of this “apocalyptic” period that saw gun-toting hippies adorn the pages of the underground press that the Weather Underground Organization was born. With an escalating war in Vietnam filling them with a sense of life-or-death urgency, the group of young college dropouts and jaded left-wing organizers aimed for a complete overthrow of the US government. To them, protests, petitions, and sit-ins wouldn’t defeat the forces of imperialism, capitalism and racism. Armed revolution, they thought, could.

A poem from the UMass collection, penned by an anonymous former member, concludes that the WUO’s mission culminated in a “dismal failure.” Yet, scholars contend that their legacy is more nuanced.

The Rise and Fall of the WUO

Known first as the Weathermen, the WUO emerged from a massive campus-centric organization called Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) which held its first meeting in 1960.

Varon described SDS as “the largest young people’s radical organization in the history of America,” with a vast membership that peaked in the tens of thousands in the mid-1960s and a presence on hundreds of campuses throughout the country, attaching themselves to the burgeoning anti-war and civil rights movements.

Varon characterized the late 1960s as a time of radical shift for the organization. As the war in Vietnam intensified, younger SDS members felt that large-scale protests, civil disobedience, and teach-ins weren’t cutting it. They began to split from older SDS members who were embracing electoral politics.

A critical history of the WUO written by an anonymous former member in 1977 is part of the archival collection at UMass’ DuBois Library. An introduction to the 52-page paper describes SDS’s evolving ideology in the late 1960s.

“The Civil Rights/Integration struggle became the Black Power movement. The teach-ins started out debating whether the US was using the most effective means ‘to bring democracy to Vietnam’ and concluded that the US was the most undemocratic and reactionary power of all,” the document reads.

Citing conversations with former members of the WUO previously involved with the student movement, Varon says that the late 1960s SDS “became infatuated with versions of Marxism-Leninism and Maoism,” letting go of a more participatory, democratic structure that had guided the group in its early days.

It was here, at the tail end of the 1960s, that SDS would hold their last meeting, as warring factions vied for control over the once humble student movement that became a formidable force in the anti-war struggle.

Lasting four days in June of 1969 at the Chicago Coliseum, a core goal of SDS’s final conference was to figure out how the group would define the working class.

During the convention, the WUO’s founding members would publish their manifesto, “You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows,” alluding to lyrics in Bob Dylan’s song “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” In this manifesto, the Weathermen argued that the working class struggle was international, painting revolutionary movements in the so-called Third World as part of a global anti-imperialist agenda, calling for similar revolutionary action in the U.S. They cited the war in Vietnam and racism in the United States, and their wider implications, as existential threats to humanity.

The Progressive Labor Party, a rival faction of the Weathermen within SDS, was expelled from the organization, with the Weathermen taking over SDS’s offices and printing infrastructure for its widely circulated counterculture publication New Left Notes.

The Weathermen “basically throw [SDS] over the cliff as a kind of pre-revolutionary petty-bourgeois formation,” Varon said.

With two opposing factions claiming to be the “real” SDS, the group was now nebulously defined, far removed from the organized mass movement they had been earlier in the decade, according to Varon.

“You could look at this as a kind of a tragedy in terms of the power that they had and then squandered,” Varon said. “Some of the former members do express regrets at having pulled the plug on SDS.”

In the summer of 1969, communal Weathermen houses, typically with a dozen members each, sprouted up across the country, checkering cities on the East and West coasts, with the Midwest being a hub of Weathermen organizing.

Chicago was the center of operations with the Central Committee of the Weathermen having the final say over decisions that filtered up from the semi-autonomous Weathermen houses across the country. The Chicago Weathermen collective was right down the street from the Chicago Black Panthers headquarters.

Coming out of the final SDS convention, The Weathermen would organize the Days of Rage, a widely publicized mass riot in Chicago, seeing it as their first of many confrontations with law enforcement and American society at large.

Throughout the summer of 1969, the Weathermen promoted the event. They attempted to galvanize young people across the country, promising to “bring the war home,” a phrase that regularly colored the pages of New Left Notes that summer. It was planned to start on Oct. 8 lasting until Oct. 11, with several evenings of marches and targeted riots.

Organizers expected thousands from across the country to take to the streets, though they attracted few. Many of the roughly two hundred who appeared on the first night were already Weathermen. By the end of the weekend, hundreds of demonstrators were arrested, dozens of police officers were injured and one was even paralyzed. Police shot several Weathermen, though none died.

The action faced condemnation from large swaths of the American left, with Fred Hampton, a senior Black Panther in Chicago, calling the Days of Rage “Custeristic,” or suicidal. He blamed the Weathermen for an inevitable increase in the policing of radical movements, particularly Black Power groups. This stung the Weathermen’s leadership, as they cited support for the Black Power movement as an impetus for their founding.

The Chicago Police Department killed Hampton in his apartment in coordination with the FBI less than two months later.

“The Days of Rage demonstrated how isolated they were while also contributing to their sense of being the only righteous white people who understood the moral necessity to wage armed struggle with this level of risk,” Varon said of the Weathermen’s first action.

Going into 1970, the Weathermen began to shift their strategy. Abandoning hopes of fomenting a mass movement, feeling that the Days of Rage proved it untenable, Weather cells began to entertain targeted bombings, embracing the limitations of their small numbers and compartmentalized structure.

Ron Jacobs, author of The Way the Wind Blew, spoke to the competitive nature of Weather collectives at the beginning of the 1970s, claiming that different cells across the country “felt that they needed to provoke a situation.”

One of these cells, based out of New York City, was planning an act of mass murder. In February of 1970, Cathy Wilkerson, a founding WUO member, holed up with a dozen other Weathermen in her wealthy father’s Greenwich Village townhouse while he vacationed. The group had dynamite delivered to the home shortly after settling in, and considered targets to bomb. Terry Robbins, a Weatherman who participated in the Days of Rage, pushed heavily to target a military dance at Fort Dix, a point of departure and return for US soldiers deployed to Vietnam.

On Mar. 6, the day of the planned attack, Robbins accidentally crossed the wires on the nail bomb he was building and destroyed the townhouse, killing himself and two other Weathermen. Dazed but uninjured, the surviving members escaped from the rubble and evaded law enforcement.

Varon describes a “mad scramble,” after the townhouse explosion, with Weathermen being forced to move underground, given the intense FBI scrutiny that followed. It was here that the Weathermen effectively became a clandestine guerilla movement.

The national leadership of the Weathermen convened at the end of 1970 embracing symbolic attacks and condemning the targeting of human beings. In the following years, the Weathermen would carry out dozens of bombings on government and corporate targets across America, typically timing their explosives to go off in the early hours of the morning, and issuing warnings to ensure janitorial staff or security guards were unharmed.

Following the end of the Vietnam War, the WUO, which had already been more or less a pariah in the eyes of the greater left, became even less relevant. Ending the war, one of their founding goals had become a concern of the past. As different Weather cadres began to entertain the idea of turning themselves in and focusing on a more conventional strategy of organizing working people, growing tired of the underground lifestyle, the group began to split apart.

At a conference of various left-wing organizations in 1976, WUO members faced scathing critiques from their peers, particularly Black and Hispanic organizers who decried them for limiting the involvement of people of color in their struggle.

Pre-existing schisms within the WUO widened after the conference. Members were compelled to draft brutal self-critiques, a practice typical of organizations with Marxist-Leninist bends. Many male members confronted their “male chauvinism” and members of both genders scrutinized their own “white privilege.”

Citing conversations with Mark Rudd, a founding WUO member, Varon says the former guerilla “feels completely comfortable saying that at its worst, [Weather] had elements of a cult.” The only distinction Rudd drew, according to Varon, was that cults typically revolve around a charismatic leader imposing their idealogy on devoted followers. “In this case, they did it to themselves,” Varon said.

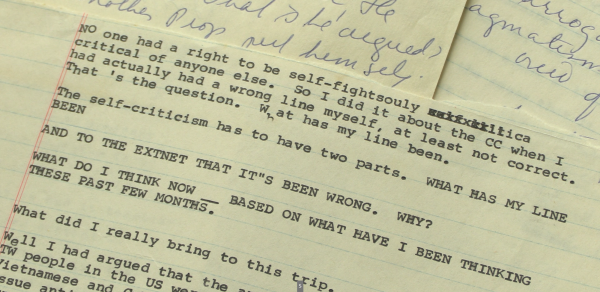

The DuBois Library collection contains numerous drafts of these self-criticisms written in the late 70s by an anonymous former member who has since passed away, according to Jeremy Smith, a UMass archivist. Printed on a typewriter, they contain copious hand-written edits reflecting deep-seated insecurities and conflicted thoughts on the WUO’s purpose and legacy.

Various Weather Underground members surfaced following the 1976 conference, serving short jail sentences and paying fines, with many of the most serious charges dropped due to illegal conduct on the part of the FBI. Varon says that by 1977, the WUO was effectively dissolved. Members who remained underground split off into other radical groups that dissolved by the mid-80s.

The WUO’s Legacy

Modern discourse surrounding the WUO’s legacy often focuses on the efficacy of violence as a political strategy. Others tend to focus on their high-profile failures, like the townhouse explosion or the shattering of SDS.

Varon and Jacobs see the WUO’s impact on American society and culture as far more nuanced. Varon argued that in focusing on the dramatic appeal of militancy, modern scholarship on the WUO has “depoliticized the whole movement.”

He sees the WUO as playing an important role in introducing an analysis of white privilege to the American mind, considering that the concept is more or less mainstream today. Yet, he hesitates to call them pioneers of the idea.

“It becomes a little dangerous because there is this whole anti-woke literature,” Varon said. “If you trace the line too strongly, you give ammunition to people who say that these were always seditious, destructive ideas rooted in America hatred.”

Jacobs similarly contends that the WUO weren’t the first leftists to vocally critique white privilege and patriarchy, but through grabbing the country’s attention with their militancy, they were able to amplify those concepts to the masses.

As for the WUO’s ambitious revolutionary mission, both authors agree that they were impatient, with Jacobs citing militant struggles in Vietnam and Palestine as decades-long, multi-generational efforts.

The WUO thought they could overthrow the United States “before their kids were grown,” Jacobs said.

Both Jacobs and Varon highlighted the Weathermen’s commitment to their cause, mentioning how they threw away a privileged existence, with many coming from wealthy families, risking imprisonment to live underground for years, truly believing that they could succeed.

“These were people that were willing to give up everything,” Jacobs said.

Varon and Jacobs spoke highly of the group’s critiques of American society and their diagnosis of the country’s core failures. Yet they attributed the group’s alienating strategy and rigid ideology as essential to their collapse and inability to effect meaningful change.

“They took a global revolutionary fervor and then projected it onto a country whose consciousness was in a different place,” Varon said, “and then they paid the price of their error.”

This article accompanies Dan McGlynn’s award-winning short documentary, “Piece Now: The Rise and Fall of the Weather Underground Organization”, premiering Friday, September 26 on Vimeo and YouTube.