By Dean Allsopp

A new business model has revolutionized the fashion industry, changing everything from how consumers shop to how clothes are produced.

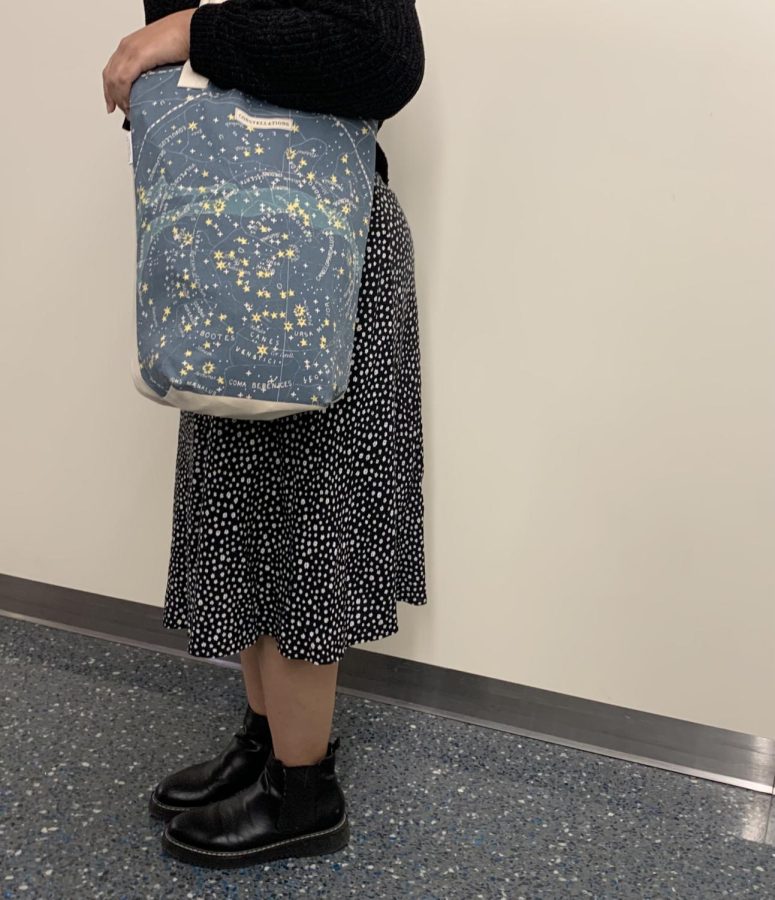

This model, called “fast-fashion,” has made trendy clothing affordable, so much so that budding fashionistas “can hardly do any wrong,” says Niani Tolbert. Tolbert is a Mount Holyoke student and author of the fashion-diary blog The Fierce.

Tolbert believes the fusion of trendy clothing and affordable prices is irresistible for consumers.

“I mean, if you’re really trying to find something trendy, something very cute, the prices are there. It’s hard not to go for the trend,” says Tolbert.

Fast-fashion describes the new method of retailing inexpensive, stylish inventories throughout the year, instead of the traditional model of seasonal selling. The pioneer of this method, Zara, delivers new lines twice a week, while H&M and Forever21 get daily shipments.

New arrivals draw in consumers at alarming rates; Zara customers visit the store seventeen times a year on average. Constant consumption results in small profits on thousands of products, a system so efficient that fast-fashion retailers make almost twice the average profit margin compared to traditional competitors.

So what are the tangible benefits for the American consumer? Unfortunately, there aren’t many. Attention fashionistas: our quest to fill our closets with trendy apparel destroys the environment, lowers product quality and exploits workers in the industry.

Most shoppers can acknowledge the noticeable lack of quality of fast-fashion retailers. The labor-intensive details are sacrificed in order for companies to turn a profit on the cheaper products. It has gotten so bad that “there are very few high-quality garments being produced at all,” says Elizabeth Starbuck, designer for sustainability aware clothing line Bright Young Things. Starbuck says construction has been so drastically compromised that “people are wearing rags, basically.”

Additionally, these “rags” are produced by a system that exploits its workers. Although the fashion powerhouses are seeing enormous profits, worker paychecks are so low that Nike could afford to double wages of its estimated 160,000 shoe factory employees without raising consumer prices at all, according to Jeff Ballinger, a former Webster University labor studies professor.

The rapid production also creates less than ideal conditions. Many workers are forced to work exhausting overtime and safety is a big concern in these overcrowded workspaces. Just in 2010, two factories producing garments for H&M and Gap killed twenty-one people and twenty-seven people respectively.

Our wardrobes also carry a hefty carbon footprint. Lucy Seigle, a journalist in the UK, found that over 145 million tons of coal and between 1.5 trillion and 2 trillion gallons of oil are used annually to produce fiber worldwide. Another reporter, Stan Cox, found that just the U.S. cotton crop demands over 22 billion pounds of weed killer per year. Since international factories aren’t bound by our domestic EPA restrictions, factories often dump waste locally, destroying delicate ecosystems.

Once we tire of our clothes, we assume that they are reusable and therefore not bad for the environment. According to Elizabeth Cline’s book “Overdressed,” only 20 percent of clothing is resold to thrift stores.The rest ends up in a landfill or is exported to Africa; in such droves that one estimate states clothing as the United States’ number one export by volume.

Worse still, fast-fashion’s preferred fabrics aren’t decomposable, as many are blended with polyester (a form of plastic) and the technology doesn’t exist yet to separate these fabrics to their original state. We avoid buying bottled water because we know it takes thousands of years to biodegrade, so why do we make exceptions when it comes to clothing?

Fast-fashion’s business model is not sustainable, yet the future is not as dismal as one would expect.

“There are signs everywhere that cheap fashion is coming to an end,” says Cline. We can all be more conscious about what is involved in producing our clothes. Just like the movement for local, sustainable food, let’s make a movement for the fashion industry to do the same. Let’s make a commitment to buy locally produced, high quality clothing, that’s classic and will last. The first step towards change is viewing our clothes as an investment instead of a disposable item, and after that realization, the price tag on a moderately priced garment is much less terrifying.

As Tolbert says to students “find something that really interests you, and only buy something if you’re truly in love with it.”

What do you think? Will fast-fashion continue or will consumers start to change their habits? Post your comments and let me know!

Dean Allsopp can be reached at [email protected]