Late one night during Jason Rollins’ freshman year of high school, his head began swirling. Planning to go to bed, he went up to his room, but before he could even process what he was doing, he had grabbed a swiss army knife and poised it toward his body. He can’t remember how long he held it there before finally putting it down. Something was obviously very wrong.

“That’s what really fucking scares me,” recalls Rollins, now a graduating senior at UMass Amherst. “Even to this day, I can’t fathom what I must have been thinking.”

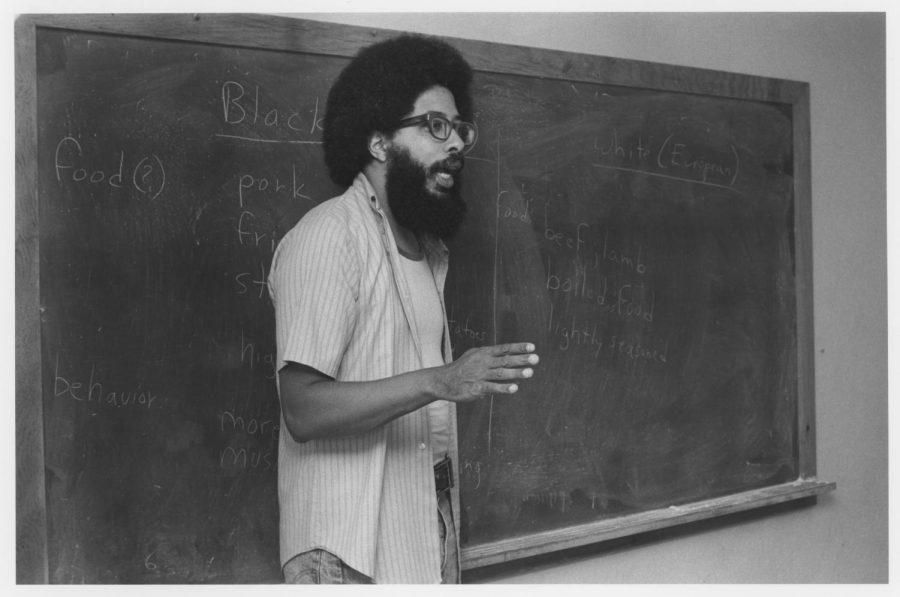

Years later, tucked away in a corner of UMass’ integrative learning center, Rollins has agreed to be interviewed for a documentary about his experiences with Zoloft – an antidepressant. Constantly asking if a mic needs to be positioned a certain way or if the camera needs a second to adjust, he’s apologetic, often looking to see if he misspoke or needs to repeat a sentence for the camera.

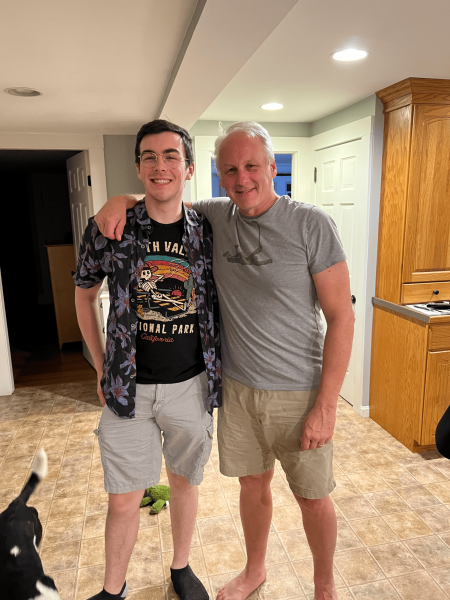

Off camera, he’s more relaxed, beaming a wide grin and bouncing around when he walks. When Rollins talks he fills the room with his voice, constantly joking around–refusing to take himself too seriously. He wears plain dark blue jeans and a pair of white New Balances with an orange accent but he balances this simplicity out with a worn black shirt that says “The Beagles” – a parody of the Beatles – and pumpkin socks in the middle of May.

Just one year earlier, Rollins had been diagnosed with depression. Rollins had gone to his mom’s salon to get a haircut. Leaves were strewn about, a gentle breeze hit his face and the sun warmed his skin. This was no ordinary haircut though. He had been planning something bold; something new after an era of living with neck-length hair.

Walking out of the salon, the left half of his head newly shaven and the new sensation of a breeze on his scalp, he had finally done something that he wanted. But his mom seemed less than thrilled.

“It seems like there’s something you want to say,” his mom seethed.

Silence filled the car for a while when suddenly he blurted out that he hated himself. Stunned, they sat for a bit longer.

It was jarring for him as he’s usually someone who thinks carefully about everything he says, considering the consequences. This time though, there was no thought, no preparation, just instinct.

“I knew that was something that if I didn’t get it off my chest it was going to be on my chest for the rest of my life,” he admits.

Confused, hurt and concerned, his mom probed him about the new haircut. He was angry. This was the reaction to something he wanted to do so badly? After more conversation and a long car ride home, his mom told him that he had to talk to his doctor about these feelings.

That week, he went to a routine physical. He filled out a survey noting how often he was anxious and how he disliked his self-image, checking all of the boxes for depression along the way.

Today, Rollins has been on antidepressants for a year. “That day was, I would say, the turning point where I was like, ‘Okay, things from here prior have been an absolute nightmare,’” recalled Rollins.

Per the World Health Organization, 280 million people worldwide suffer from depression; the largest demographic being 18-25 year olds, who make up 17.2%. In recent years, depression in young people has only gotten worse. Antidepressant usage itself has increased in recent years with a 64% rate increase during the coronavirus pandemic. Not everyone leans on others during difficult times, though.

Men who are diagnosed with depression or anxiety only seek help about half of the time and they are about four times more likely to die from suicide than women. Per the National Center for Health Statistics, of a sample size of roughly 54,000 U.S. citizens from Apr. 27 to May 9, 2022, 44.7% of people said they experienced symptoms of depression or anxiety in the four weeks prior and went out to get treated through medication or counseling. 33.1% of women reported these symptoms and got help, whereas only 20.2% of men responded similarly while also seeking professional medical care.

Today, Rollins remembers with dread what it felt like to be depressed. It took a long time to feel comfortable enough to seek assistance. He felt like a burden in the eyes of his friends and family — his headspace reiterating to him that his friends hated him, his family hated him and his partner hated him.

For Rollins, depressive episodes made everything worse. The tiniest things triggered him; He could see something innocuous–like a photo of somebody smiling–and just start spiraling. Minor inconveniences could make his entire day go down the drain. The worst part was that these mental lapses were inevitable. It got so bad that at one point, Rollins would try to amplify these negative feelings so he could get the process of recuperating over with sooner.

“Your mental state is being controlled by something else, there’s a force in your head that’s greater than you – that has more control than you do,” said Rollins.

Part of the battle of depression is how cyclical it is, even after diagnosis and treatment. During an add/drop period at school, Rollins ran out of his medication for a few days. As his anxiety rose, he started worrying about what classes he would get into and kept spiraling until he was on the floor of his dorm room, hyperventilating. The fear of regressing into the person he had been consumed him.

“It’s something that’s going to be [a] part of me for the rest of my life,” said Rollins. “And I’ve tried to make peace with that fact. But there’s always, always the worry that one of these days, it’s going to claw its way back out of whatever pit it’s been dug into.”

But the negative thought patterns he used to confront are now manageable. A dreadful thought or event will arise and he can size it up and move on. Feathery Wings by Aurelio Voltaire and Space Song by Beach House: two songs that used to bring pain and suffering just ignite nostalgia, a reminder of how much he’s grown.

Rollins also makes an effort to enjoy the little things in life. Be it blowing bubbles, drawing in his sketchbook outdoors or walking around and seeing ducks on the pond under a clear sky. “I have so much love for the people in my life,” he says. “There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t appreciate what they did for me.”

He often stops and reflects on all the joy he experiences now and wishes he could share that with his younger self. What he would give to tell that kid everything was going to be alright.

“I didn’t think that I would be alive today,” says Rollins, recalling his high school self. “So just being able to say ‘Oh, I’m going to have an apartment or a house; someday I’m going to get married to somebody; … just having that peace of mind … is already just amazing.”